Proctor’s first foray into writing started in 2001. “I was experiencing ‘empty nest syndrome’ with my son having left for college. In addition, I was suffering anguish as a result of 911,” she said. “I needed something to dig into that would distract me.”

She found the very thing – researching and writing about her family’s history. She traced her lineage back to County Armagh, Ireland, to her great-great-great grandfather, James M. Liggett. Her family’s story is classic American pioneer: Liggett landed in Philadelphia as an indentured weaver and later moved westward to homestead in Nebraska. His grandson migrated to California.

“I derived many benefits researching and writing about the Liggetts,” said Proctor, “I had the pleasure of getting to know members of my extended family here and in Ireland.”

In her next writing project, she tackled her neighborhood west of Twin Peaks. “When I visited San Francisco as a child, I fell in love with San Francisco’s architecture and natural land preserves,” said Proctor. “When I completed my family’s genealogy, I began to seriously explore the west of Twin Peak’s history.”

It all started with a tunnel

She learned how the area first developed due to the boring of the streetcar tunnel through Twin Peaks in 1918. The tunnel opened the land around Mt. Davidson, the city’s highest hill at 928 feet, for development. The California Supreme Court granted A.S. Baldwin the right to develop this area. With noted engineers and architects, Baldwin created Craftsman, Art Deco, English and Spanish style houses on curvy landscaped boulevards.

During the 1920s through the 1960s, developers cut more into Sutro Forest, creating the new neighborhoods of Forest Hill, St. Francis Wood, West Portal Park, Balboa Terrace, Mount Davidson Manor, Westwood Park, Westwood Highlands, Monterey Heights, Sherwood Forest and Miraloma Park. The architects added lush landscaping, decorative street furniture, gateways and staircases to these “residential parks.”

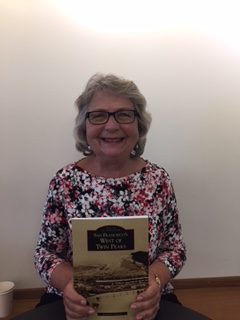

In “San Francisco West of Twin Peaks,” published in 2006, Proctor lays out in the rich history of these neighborhoods with pictorial splendor. “My publisher wanted 200 photos and the library charged $50 a photo, so I asked friends from the Mount Davidson Conservancy for their family pictures,” said Proctor, a co-founder of Friends of the conservancy. “I met such wonderful neighbors.”

Proctor joined the movement to protect the land at the top of Mount Davidson. Organized in 1996, its mandate was to carry on the work started by State Park Commissioner Madie Brown, who worked alongside other women in 1926 to create the 38-acre park on Mount Davidson.

“I am proud of the work we did to negotiate a 5.62-acre reduction in the amount of park land to be sold by the city,” said Proctor. “The privately owned portion of the park land will now be preserved, and any new construction prohibited.”

Spectacular views, friendly neighbors

Proctor had had a long time to get to know her neighborhood before she started writing about it. She and her husband, Ron, bought a house in Miraloma Park in 1980. She then began to explore Mt. Davidson and surrounding environs. “I can see the Mt. Davidson Cross from my living room window and the East/South Bays from our rear yard deck. It’s only a 15-minute walk up to the park. Our son played there as a little boy,” she said.

The Proctor’s were attracted to Miraloma Park because of its affordability. They grew up in the suburbs, so they liked that their house had space for front and rear gardens as well as a garage. “Our two-bedroom house has a Colonial Revival design,” Proctor said. “With friendly neighbors, convenient shopping and spectacular views, the location is ideal.”

Proctor graduated from San Diego State with a degree in sociology but found that working with troubled youth was not her bailiwick. However, through her studies and the influences of writer and community activist Saul Alinsky, she became very interested in social change.

Deciding on a career in public administration, she obtained her master’s degree in 1977 from what is now California State University East Bay, and started working for Hayward’s city government. Throughout her 30-year long career, she found that writing was what held her interest. “I worked on “engineering translation” – English as a Second Language papers, public reports, newsletters, city council reports, newspaper articles and more,” Proctor said.

After the publication of “San Francisco West of Twin Peaks,” she was contacted by the great-granddaughter of Harold G. Stoner, an architect of many of the homes in the area. “His great-granddaughter asked me to write a book on him because even though he was a big part of the development there, he was little known,” said Proctor.

Guided tours

The result was “Bay Area Beauty; The Artistry of Harold G. Stoner, Architect,” published in 2011.

Stoner, a British émigré, designed a medieval mansion for Adolph G. Sutro on top of Mt. Sutro called ‘La Avenzada,” an ice rink and The Tropic Beach Façade at the Sutro Baths. He also designed hundreds of homes in and around San Francisco. “Stoner could leap from designing the storybook cottage, to Art Deco, to a Spanish castle and give each a romantic air,” said Proctor. Her book includes nearly 400 specially commissioned photographs and archival images.

Delving into architectural history sparked an interest in volunteering for San Francisco City Guides. She led Bay Area residents and visitors on free walking tours of the Financial Center, Chinatown and South of Market. She even created her own tour, the “West Side Whimsy Walk” encompassing the areas west of Twin Peaks.

Proctor plans to continue walking through history, but not writing about it.

“Going forward I still plan on conducting walking tours for City Guides. I’m also going to focus on taking classes at OLLI (San Francisco State’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute) and doing some traveling,” Proctor said. “I’ve devoted the last 10 years, since age 55 when I took an early retirement, to my beloved neighborhood and now I feel it’s time for a shift.”