Filmmaker keeps crafting winners, despite loss of Academy Award-winning partner – her mentor and husband

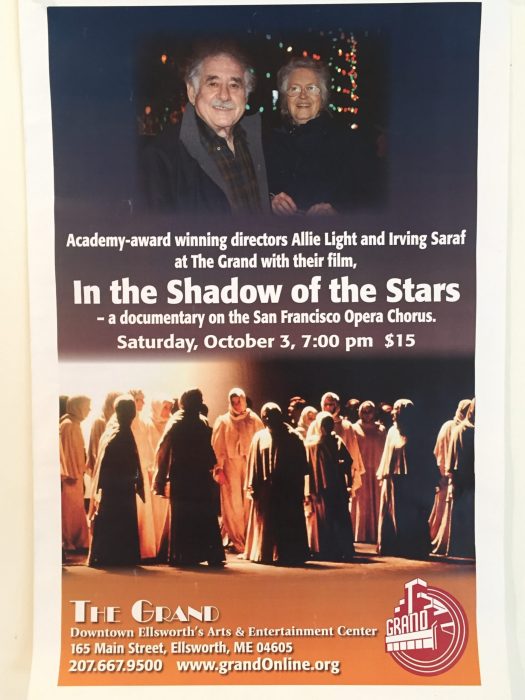

It was not Allie Light’s first brush with an Academy Award. But the first one without her husband, a noted filmmaker and her mentor. In 1991, Light and Irving Saraf won best documentary for “In the Shadow of the Stars,” which explored the lives of the San Francisco Opera chorus.

This year, 28 years later, a film she produced without him was considered for an Academy Award. “Any Wednesday” portrays the relationship between an older woman with dementia and a young army veteran with PTSD.

Saraf, who died seven years ago, was a film producer, editor, director and academic. He had more than 150 film and television production credits to his name. He founded the documentary film division at KQED and helped producer Saul Zaentz build his Fantasy Films studio.

“Irving and I were partners in life and in the movies,” said Light, 84. “He taught me everything about filmmaking.”

Light and Saraf met in Noe Valley, while neighbors in separate marriages. They became friends through their children. And she and Saraf shared an interest in poetry. Years after Light’s husband died, of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at the age of 33, and Saraf had divorced, they reconnected. They married in 1974, each bringing three children into their new family.

By then, Light was teaching in the Women’s Studies Department at San Francisco State, where she had earned a bachelor’s degree in English and creative writing and a master’s in Interdisciplinary Art. It was Saraf who drew Light into filmmaking.

A personal and professional partnership

They formed a professional production partnership, Light-Saraf Films, in the early 1970s. Their first film was “Possum Trot,” a documentary about a married couple who were folk artists in the Mohave Desert. On a road trip there, Light and her daughter met Calvin and Ruby Black, whose carved dolls were attached to windmills. The dolls moved, talked and road bikes when the wind blew. She and Saraf went back on their honeymoon to shoot some of the film.

Their genre was documentary, and their subjects varied widely – from people: folk artists, Asian-American poets, a radical nun to industries and issues: opera, breast cancer (“Rachel’s Daughters” on HBO) and homelessness. They operated as a team of equals, though not without conflict.

It was in the editing room where their differences arose, sometimes erupting into frustration. “One day Irving took my purse, walked around the room, and dumped out all its contents.” Light threw a glass of cranberry juice onto a poster of Friday Kahlo. “It just ruined it.” After that, they made a rule, that there would be no liquids on the editing table.

As they got older, “We controlled ourselves better,” said Light. But they both could be very stubborn about editing decisions. Saraf always reminded Light, “You could love something so much, it could be the best thing you ever shot, but if it doesn’t work, you have to take it out.”

Saraf was her greatest but not her first influence in the realm of film, she said. Her yearning to become a poet and writer put her in a milieu where all things were possible – including unions with other creatives.

A brief second marriage to an artist and a photographer helped her learn to ‘see’ rather than ‘read.’ “We went to a lot of museums; now I’m much more visual.”

The conversion to film begins

Her first husband, Charles “Chaz” Hilder, kick-started her education in film. “He wanted to see a D.W. Griffith film, ‘Intolerance.’ I thought Griffith was a foreign filmmaker, not a great American one.” Hilder also provided the fodder for “In the Shadow of the Stars.”

Hilder and Light lived in Noe Valley in the 1950s and ’60s with their three children. They were neighbors of the Saraf family and became friends through their children. Hilder was a tenor in the San Francisco Opera chorus. “Chaz wanted so much to be an opera star, but he had to support his family, working as a teacher, because in those days chorister work was part-time without benefits,” Light said. “So, he couldn’t put in the work that goes with becoming a star.”

But something he did while onstage eventually lead to fame of a kind: He shot video of the stars with a tiny camera hidden under his costume. Hilder died of non-Hodgkins lymphoma at the age of 33. Later, married to Saraf, Light still had that footage. Discussions about what to do with it sparked the idea for their Academy Award winning documentary.

A subject in her own documentary

It was while married to Hilder that Light herself experienced something that would lead to another award-winning film, in 1994. “Dialogues with Madwomen” profiles eight women who experienced mental illness as a result of child sexual abuse, conditions of extreme poverty, homophobia, misdiagnosed medical conditions and domestic abuse. It garnered an Emmy.

Light herself is one of the subjects. Her experience arose from three difficult pregnancies. She suffered severe morning sickness, now known as Hyperemesis Gravidarum, “which didn’t have a name back then,” Light said. “So, through all three pregnancies, violently throwing up, doctors – one administering Thorazine – blamed me for my condition.”

After the birth of her third child, worn out and sick, Light slipped into “what felt like depression. I had anxiety, panic attacks and heart palpitations.” She was prescribed with the anti-psychotic drug Thorazine. Finally, in 1963, “after hitting bottom,” she committed herself to a weekday, outpatient program at Langley Porter Institute, part of the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

“After three months I had had enough of Thorazine, playing table tennis and being told if I just cleaned house and cooked turkeys, I’d be cured,” Light said. “I left there no better than when I came in.”

After Hider died, Light found a doctor at Kaiser who told her she had the lowest Thyroid count he’d ever seen. “He put me on medication, and even though I was grieving and taking care of my kids alone, I felt better.”

The path that eventually lead her to the world of film and Academy Awards wasn’t an easy one. But humble beginnings had given her an early taste of hardship.

A Dust Bowl immigrant

Born in Colorado at the height of the Depression, Light had to escape with her family from the small farming community of Dove Creek Colorado, six miles from the Colorado and Utah border. They had hardly any food. “My brother had starvation diarrhea,” Light said. And, her father had joined the Communist Party, something his neighbors frowned on.

“My father was a desperately poor farmer, working for food, when an ‘interesting’ group of people convinced him that a poor man could feed his family under a different economic system,” Light said.

They headed to San Francisco because her father had heard there were jobs at Bethlehem Steel. He had to renounce his party membership to get a job with them, which he did.

“Like other Dust Bowl immigrants, we came here with a mattress on top of our car,” she said. “My brother and I slept on a sack of pinto beans as we drove away.”

She bore up under many hardships, but Saraf’s death – and the end of a happy marriage and collaboration – was particularly harsh. The only way she found to relieve the all-consuming pain, she said, was to write – four short dramatic scripts on grief and desire in old age.

If there’s a silver lining to be found in that sorrow, it’s that “I got to be the director I always wanted to be,” Light said.

“Any Wednesday” is the first of those scripts she

produced and directed. She’s working on the next three.