Foster grandparent goes extra mile to help at-risk children – whose determination ‘never fails to amaze’

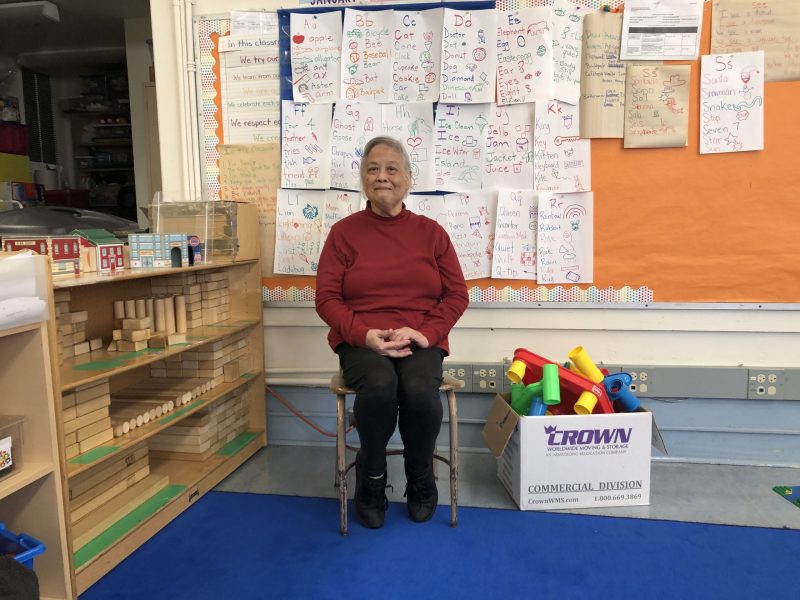

When Carol Chuo retired in 2017, she decided to “take what I know and turn it into pure fun.” Having spent 23 years working and playing with children as a teacher’s assistant for the San Francisco School District, raising two daughters along with five grandchildren, she volunteered to be a foster grandparent.

She said it was the perfect balance of everything she loves with everything she does well. She is a mentor, tutor and overall advocate for at-risk children in reading, language and arts development along with socialization.

“It has been a great experience. I’ve found new friends, earned some extra money and created a solid structure after I retired,” she said. “And most significantly, I help kids become better citizens.”

The foster grandparent program is run by the Felton Institute, a federally funded Bay Area social services organization dedicated to helping low-income families, adults, the elderly and people with disabilities in an array of 46 programs in 11 languages. It was created in 1965, under the auspices of War on Poverty legislation, crafted with the notion that older adults are valuable resources in their communities.

The program plays a vital role in the well-being of elderly adults while improving the lives of children – infants, toddlers and preschoolers, and from kindergarten through fifth grade. With a thriving San Francisco base with 60 volunteers, the program serves 447 children and youth in 30 host sites.

Often times these recipients are under-achieving students who might be facing setbacks because of undefined learning disabilities, working parents stretched for time or troubled home lives. They come from widely ethnically diverse communities; some may be learning English as a second language. School officials decide which children need this extra help.

Dreams of being helpful

Chuo has been working with children since 1968, when she got a job through a summer teen hiring program. She was a translator at the health clinic in Chinatown, where she was born. But it was even earlier that she thought about a future of helping people. At the age of 10, her class read a book by Nobel Peace Prize winner Albert Schweitzer. “He was a medical doctor who gave it up to go help people,” Chuo said. “I thought, that’s what I can do.”

She made it through two years of college, hoping to become a sociologist. But she coyly admits, she fell in love, got married and had children. She went to work at the health clinic, and on weekends, helped her husband at his flower farm in San Jose. They eventually divorced, and she went to work as a teacher’s aide for the San Francisco Unified School District. It was with at-risk students that she felt a particular mission.

“I understood them right away,” she said. “When I was a kid, I always thought I was special ed. I couldn’t understand what the teacher was saying. I didn’t go to special ed; I was a fall-through-the-cracks kid.”

And her years of working with children taught her a lot, she said. She learned such terms as “auditory processing” – “They hear but they don’t understand.” The children in the foster grandparent program go through the usual testing, but “red flags” can come up when working with a child, Chuo said.

“I saw all their problems. They’re all labeled like they’re going to fail in life. I was told I wouldn’t amount to much by my parents and teachers. I used to have anger.” She later learned she had probably long been depressed. “Now, I am very patient with them.”

Going the extra mile

Chuo, 69, is well recognized by Felton managers and co-workers for going out of her way to help children. She seeks out libraries, bookstores or any place that can fulfill a child’s wish list. A bright third-grader with whom she had built a special rapport got his heart set on learning to use a “diabolo,” the Chinese spinning yo-yo. He told Chuo about the hour-glass toy, and that became her mission.

“I felt the excitement in this child’s voice and eyes,” she said. “As this child was determined to learn this activity, I became just as determined to make it happen.” She doesn’t have a computer, so couldn’t search for it online. Instead, “I checked out 10 different Chinatown stores and finally found it” for him.

But she also encourages her students to apply a “can-do” approach and get things done themselves. When a second-grader asked her to get an old fable she wanted to read, “I told her to go to the library; try to find it herself.” Ironically, said Chuo, the book was “The Little Red Hen,” about a hard-working hen that couldn’t get anyone to help her make bread. So, she grew the wheat, milled the flour and baked the bread herself. Afterward, those who wouldn’t help were eager for some of her delicious bread.

“The kids never fail to amaze me; when they get their heart set on something— they don’t quit.” she said.

Making things click

The foster grandparent impacts the child in different ways, outside of his or her communication with teachers, parents, and other adults, said Chuo, who works 28 hours a week between Spring Valley Elementary School and Lee Woodward Women’s Resource Center. “Often times, it is the intuitive foster grandparent who breaks through to the troubled kid and speaks those magical words that launch a new path of growth, understanding and social skill.”

When helping her students with their schoolwork, “I tell them there are 100 ways to learn to do this. I show them – I’m trying to make something click.”

For example, her students were finding it hard to comprehend a lesson plan on water conservation, presented in text and statistics. So, she drew a picture of a globe, marking the 70 percent of water that makes it up and a single line to show the 1 percent actually available for use – for drinking, cleaning, agriculture. Her approach worked, she said, and afterward, one young man promised, “I’m going to turn off the faucet when I brush my teeth.”

“If you have the heart and you are able to inspire children, it doesn’t matter what educational level you are at. You can become a great foster grandparent,” Chuo said. Her advice: “Don’t judge children so fast … you don’t know what they’ll grow up to be. Everyone is different; we learn differently.”

The Foster Grandparent Program is always looking for volunteers, who get lots of training and ongoing support. “Making the right fit is important,” said Tieu Ly, program director. Before any host assignment is made, the volunteer undergoes three days of pre-service training and orientation, and a tour at the prospective host site where various issues can be worked out. While on the job, classroom teachers, assistants, and the site coordinator are available to give support. Monthly meetings with speakers address the various issues that come up.

Volunteers welcome

Candidates must be 55 or over, of low income, available for 15 to 35 hours a week, and able to commit one year of their time. There is a small, non-taxable stipend, paid vacation, sick time and birthday – and what Ly called an “over-the-top” annual recognition luncheon with singers, dancing and door prizes.

Folks with bilingual abilities (Cantonese, Mandarin, Tagalog, Russian, and Spanish) are especially welcome, Ly said. But the basic requirement – the first question asked – is “Do you enjoy working with kids?”

For more information, contact Ly at 415-751-9786.