We are living in difficult times, said Conny Ford. So, at 70, she has no intention of sitting back and putting her feet up. “I continue to work because it is what I have done for almost 40 years and what I believe in.”

Nationally, things are pretty messed up, but locally, she said, “I have an avenue to be part of making the change that is necessary to counteract those who are trying to continue to turn San Francisco into a city for only the wealthy.”

Ford is actually retired from paid work but is just as busy as vice president for community activities for the San Francisco Labor Council. The position gives her the opportunity to commit her full energy to the causes she loves: union organizing, community building and creating a more humane society. She supports herself with a pension, Social Security and income from SF Clout, a labor education nonprofit she started.

Through more than 35 years of union membership and community organizing, she has logged some significant successes. Ford recounts the struggle to unionize workers in homeless agencies, many of them formerly homeless themselves. While the churches and nonprofit organizations that provided these services were initially hostile, “as they see we are able to bring members better wages and benefits, there is more acceptance from both sides of this working relationship.”

‘Union and community members are one’

Ford’s organizing has not been confined to her union work. Jobs with Justice San Francisco, now in its 11th year, was key to raising San Francisco’s minimum wage, the strongest minimum wage law in the nation. JWJSF also led the fight for healthcare for all San Franciscans, the right to marry whomever you want, legislative paid sick leave days and free City College for all who live or work in the city.

“As we say, union and community members are one, as all workers go home each night and join community members, participate in PTA meetings, go to church, synagogue or mosque, and carry things forward within their neighborhoods,” she said.

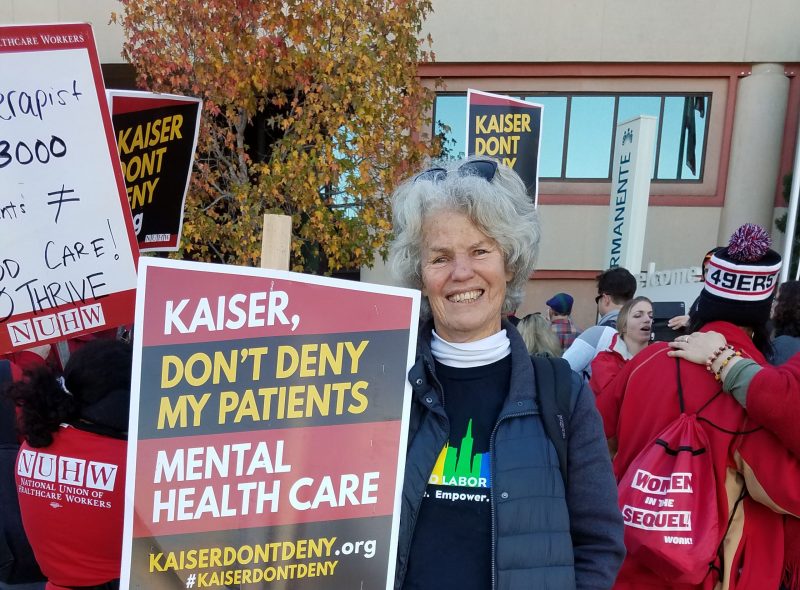

Today, she said, she and other union organizers are looking to get a handle on the housing crisis and develop a strong immigrants rights alternative to the national narrative and decide how to best support a new mental health system within the city.

Ford became a union member when looking for a job that paid more than the bank where she worked. And the hours were long and the benefits minimal. “I was a young mother trying to raise two young children on my own,” she said.

Friends told her about an opening at a multi-union trust fund. She got the job and along with it, membership in the Office & Professional Employees International Union Local 3. “I hadn’t been looking for a union job, but the hours were better. It had medical and pension benefits, plus better vacation and sick leave policies.”

From then on, all her other jobs were in OPEIU shops. Over time, she met and married her second husband, moved into the union-sponsored St. Francis Square Housing Cooperative and rose in the union structure – from shop steward to secretary treasurer, its highest position.

In 2013, she left the leadership of OPEIU – though still a member – to work at the San Francisco Labor Council, where she was recently elected to her third term. “I was looking for something within the labor movement that was a little bigger than what a local union is able to do and, just as importantly, there was the next leader of the union, who was ready to step up and take the position.”

Raised by solid FDR Democrats

Born 70 years ago in Southern California, Ford was raised there by solid FDR democrats, churchgoers with liberal Protestant values, though they never belonged to a union. Like many of her ’60s generation, she became an activist. The Vietnam War and the women’s and civil rights movements taught them that “the fight for the betterment of our communities is not just possible, it’s doable,” she said.

San Francisco has a long history of activism to promote justice and economic rights. In 2003, San Francisco voters passed a local minimum wage law, the first local jurisdiction enacting a rate higher than the federal or state minimum. Eleven years later, JWJSF led the campaign to raise that minimum to $15 an hour – at the time, the highest in the nation. JWJSF also established a Retail Workers Bill of Rights and successfully campaigned to make San Francisco City College free for all residents.

Central to all her work is the fight against racism, Ford said, in all its shapes and forms. On a personal level, she raised her children in St. Francisco Square, a large, multi-ethnic housing built during a time when minorities could not easily buy housing. Many, including Ford and her family, have lived there for generations.

“My generation has been lucky,” she said. “Simply being born into a time when the country was trying to move forward after WWII, when funding for quality public education improved, when college tuition was reasonable, and there were jobs that paid good wages and benefits so that parents could support their families is something not to be taken for granted.”

It was not a perfect time, she conceded, especially for people of color, “but it gave many of us opportunities. Unions played a key role then and I believe will continue to play a role in the future.”

Strong female mentors

She is also lucky, she said, to have had strong female mentors, like Geraldine Johnson, an African American trade unionist who developed multi-racial coalitions. Together, they organized the 1983 march through the neighborhoods to City Hall, in celebration of the 20th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

“Molly Gold got me excited about electoral politics,” she recalled. Leah Schneiderman, who helped organize a sit-down strike at an automotive plant in Flint, Mich., taught her the power of collective action at the workplace.

Ford is now following suit, passing these lessons on to the next generation. “There are so many young women coming up in the labor movement. They are smart and talented. I remember how I learned and I encourage them.”

Part of Ford’s Labor Council job is educating people about the history and value of labor and union activism, something young people don’t learn much about, she lamented. The council is working to pilot a course in labor studies and contract negotiations in both public elementary and high schools in the coming year.

This summer, she marched and chanted for climate justice along with unions and a group called Youth vs. Apocalypse. “They said it best – ‘Another World is Possible!’,” Ford said.

“Things are very, very different now, in so many ways, but as I continue to work with a diverse and younger crowd, I remain hopeful.”