‘I’ll show them:’ After a career challenging sexism, pioneer and icon of underground comix for ‘wimmin’ fends off ageism

Reading comic books leads straight to delinquency. That’s what many parents believed in the 1940s when Trina Robbins, now 81, was growing up. Fortunately, Robbins’ family was not among them.

Robbins, who grew up in Queens, N.Y., recalls taking her weekly, 10-cent allowance to the neighborhood candy store and after studying the week’s selection, buying any comic that featured young girls and women. At home, she wrote and illustrated her own comics and dreamt of publication.

Robbins insists she did not come from a dysfunctional family. Nonetheless, by the time she entered high school, she had one goal in mind: move to the Village and be a bohemian.

A trip worth remembering

And indeed, that’s where, in her mid-20s, her career as a cartoonist started. It was an acid trip that opened the door. High on LSD, she and her boyfriend found themselves outside the office of the East Village Other, a beloved hippy underground newspaper. They sought haven. The office was empty except for its publisher, Allen Katzman, who talked them down.

“A couple of days later, I drew a kind of proto-comic to express my gratitude and shoved it under the door,” she said. “They printed it in the next issue. Thus, began my so-called career.”

Robbins is extolled for her influence on the underground comix movement – especially as one of the few women in a field dominated by men. It was the 1960s, after all. Now she is in the process of completing five books, including two retrospectives on previously unrecognized women cartoonists: “Gladys Parker: A Life in Comics and a Passion for Fashion,” and “The Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists of the Jazz Age.” She’s also working on a mini-series on the Blond Phantom, a glamorous crime fighter who wears red high-heels and a long red gown slit up to the knees.

Motivated by anger

“Trina played a tremendous role in the world of comics, through her own work in mainstream and underground comix and her scholarship,” said Nick Sousanis, assistant professor and chair of the comics studies minor at San Francisco State University. “Comics were long considered a boy’s field. In the last decade that’s really flipped. Trina had a tremendous impact in that.”

Robbins’s work was ignored for decades by the comic book establishment. Still, she persisted, eventually gaining star status along with underground comix icons like Robert Crumb. “Anger motivated me; it’s a powerful motivator.”

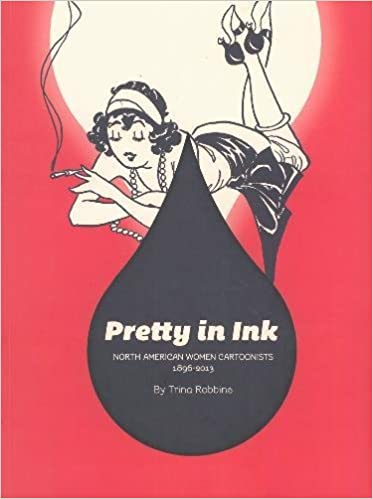

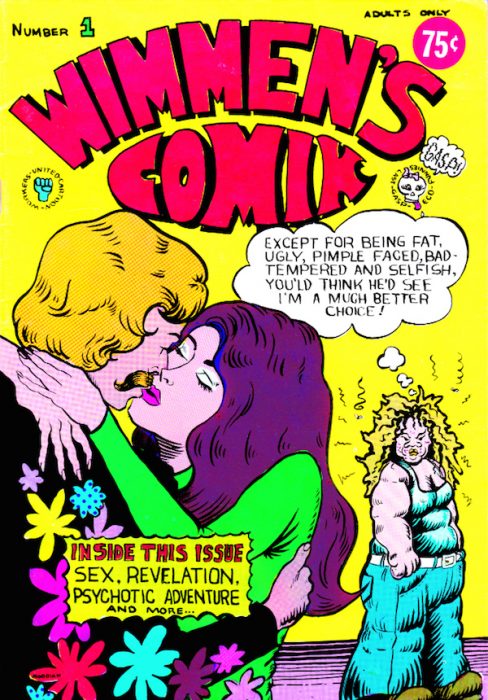

Her talent received official recognition in 2013, when she was inducted into the Eisner Hall of Fame, the comics’ industry’s Academy Awards. And her book “Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists, 1896-2013,” published that year, launched an exhibition of her personal collection at the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. She made the Eisner list again in 2017 for her work on “The Complete Wimmen’s Comix.”

When Robbins first tried to place her work, it was easy for editors and publishers to say that women didn’t read comics, since the comic bookstores didn’t carry comics for women and young girls. Not to mention females found the boy’s clubhouse atmosphere forbidding.

Women cartoonists might be contracted to illustrate romance or children’s comics, but the “big money” went with the superheroes. Comic bookstores, the prime outlet and a de facto boy’s clubhouse, saw little point in carrying series that might appeal to young women. The lack of an outlet convinced many female cartoonists to leave the field. Fortunately, Robbins held tight to her dream.

Fame of another kind

The year 1960 found her living in the fertile rock music crucible of Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon, lured by the notion that posing for men’s magazines would lead to an acting career. When Hollywood didn’t come calling, she used her design skills and a newly gifted sewing machine to sew clothes for her Rockstar pals, like David Crosby and Jim Morrison, their bands and groupies. Joni Mitchell immortalized Robbins in her classic song, “Ladies of the Canyon:”

Trina wears her wampum beads.

She fills her drawing book with line.

Sewing lace on widows’ weeds

And filigree on leaf and vine.

But being a designer and serving as a hangout for the music crowd and being a dress shop owner, even though more lucrative than comics – was not how she wanted to spend her life. So, she packed up and returned to New York’s Village, where its comics scene more active. The East Village Other celebrated her return with a photo spread proclaiming her the “slum Goddess of the lower East Side,” and adding her to their roster of cartoonists. She opened a dress boutique to tide her over.

But by the late ‘60s, the Village scene had turned sour. Drugs were prevalent. Kids were becoming addicted to speed and heroin. Storekeepers locked their doors to prevent theft. Robbins remembers being robbed by a longhaired young man who smiled as he explained, “Property is theft, so I took one of your beaded belts.”

Troubles lead to opportunity

Still, this period of countercultural turbulence spawned the underground “comix” movement. And it opened new opportunities for cartoonists.

The Comics Code of 1954, with its emphasis on “wholesome entertainment” restricted the topics comics could address. The late ’60s street scene was definitely outside those boundaries. Underground comix reflected the anti-establishment mood of the time, glamorizing drug use, casual sex and sometimes violence. They were published in the East Village Other and sold in headshops, along with marijuana.

While New York offered some prospects, the center of that scene was the Bay Area. So, three months pregnant, Robbins and her then-boyfriend drove cross-country, moving in with friends in the Mission District.

“There were at least five publishers of underground comix, and cartoonists were flocking to the city by the bay from all over the country,” Robbins said. “Life in the Bay Area was creative and exciting, and comix were the art form of the future.”

Unfortunately, the early promise of openness was misleading. The boy’s club atmosphere had not vanished. When Robbins complained that she did not find cartoons of “women being humiliated and raped or men having sex with little girls funny,” she said, “the guys called her a “feminazi” and told her she “had no sense of humor.”

She wasn’t the only female cartoonist disgusted by such content. A group of women in Berkeley had published a feminist newspaper called “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” As soon as she saw it, Robbins signed on. She designed a comic of the same name for the collective.

Women cartoonists unite

When the “It Ain’t Me Babe,” collective dissolved, Robbins joined a second women’s collective, writing, illustrating and editing stories for its “Wimmen’s Comix,” published by Last Gasp from 1972 to 1992.

“Wimmin’s Comix” with an “i,” as it was later named, focused on feminist issues around sex, homosexuality and politics. Its premier issue contained the first-ever comic strip featuring an “out” lesbian – Robbin’s “Sandy Comes Out.” The publication was a launching pad for many female cartoonists’ careers and inspired other small-press and self-published titles.

By the mid-1980s, Robbins’ skills were in high demand. Publishers hired her to produce four issues of Wonder Woman, her lifelong heroine, as well as a miniseries on other female comics characters she had enjoyed as a girl. Despite her growing recognition, the hostility of male cartoonists continued unabated.

Years of being largely ignored had taken a toll. “No matter what I drew, I was convinced that it wasn’t good enough, and soon I couldn’t pick up a pencil or gaze upon a blank sheet of paper without getting attacks of severe anxiety and depression. … I was convinced I was washed up, over the hill, a has-been. It’s a good thing that by then I was writing.” She had produced two anthologies of female cartoonists.

Graphic novel signals a turnabout

But the comics’ world was also undergoing changes. Will Eisner’s 1978 graphic novel, “A Contract with God,” with its focus on social issues – through its tales of life in the tenements – offered a departure from superheroes or female debasement. Here was a signal that serious topics – like death, war, divorce, immigration, bullying and the perils of growing up – might have an audience.

“A lot of women got into the field, and there are also a lot of graphic novels by men who didn’t want to write about superheroes.” Graphic novels had the added advantage of being stackable, which made them attractive to libraries, schools and bookstores.

Robbins eagerly embraced the opportunity, producing graphic novels for young readers on topics as diverse as American history, famous women, mythology and literary classics. Reading about Custer’s last stand, she developed “a crush on Crazy Horse, riding around in battle with a bare chest.” She laughed at the fan letter she got from a young admirer, who’d seen her illustrated version of Jane Austen’s classic “Emma:” “Dear Miss Robbins and Miss Austen, Did you work together?”

Eventually winning both acceptance and greater financial security, Robbins turned her attention to women’s place in comic history. “I wanted to bring these forgotten cartoonists back to public memory. They weren’t written about so nobody knew them.”

In 1999, she published her first historical survey of women in cartoons, From “Girls to GrrrLZ: A History of Women’s Comics from Teens to Zines.” That was followed by “Pretty in Ink” in 2013, “The Complete Wimmen’s Comix” compilation in 2016 and her autobiography, “Last Girl Standing,” in 2017.

Spurred by doubters

Robbins still makes her home in Noe Valley, where she lives with her longtime partner, an inker and artist. In the intervening 50-plus years, comic studies have become an accepted academic field, and Robbins is a popular presenter in comics classes at San Francisco State University, Sacramento State University, the San Francisco Cartoon Art Museum, as well as a keynote speaker at comic conventions.

When she’s not busy writing and speaking, Robbins studies Yiddish at the San Francisco LGBT Center and volunteers in political campaigns. She continues to pursue her passion for clothes, though chemotherapy-induced neuropathy has limited her to mending and hemming pants she buys from Goodwill – her go-to-store. “We’re judged by our looks and I’m vain, I still want to look good.”

While Robbins shattered the glass ceiling of misogyny in the world of cartooning, she now finds herself fighting ageism. Sporting a “creativity never gets old,” button on her black-belted trench coat, she announced, “Some publishers are reluctant to sign a contract with me, fearing that at 81, I’m ‘too old and won’t live to complete the work.’ I’ll show them.”