Former Black Panthers’ volunteer proud of its community work: feeding, educating, protecting and lifting up African Americans

Despite winning a hard-fought scholarship to study commercial art at the University of Miami, Katherine Campbell stayed less than a year. It was 1969 and the school had only integrated a few years earlier.

A handful of unsettling encounters left her feeling unwelcome and somewhat traumatized, so she returned to San Francisco and enrolled in City College. She felt comfortable again back at home, but a nasty dressing down over a school paper blindsided her. “I was emotionally distraught, flashing back to the events at the University of Miami,” she said.

Finding solace in an age of upheaval

The ’60s was an era of upheaval and political challenge. Just two years before Campbell went off to college, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense to challenge police brutality and build community self-determination in Oakland. It’s where Campbell would eventually find solace and a growing understanding of the social issues of the times.

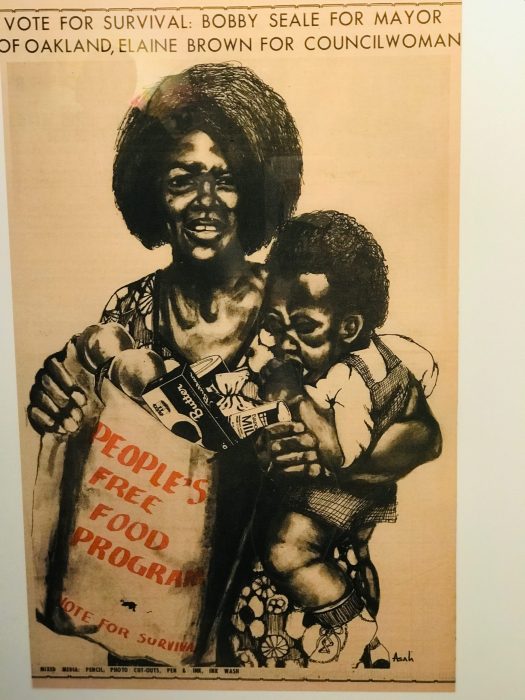

The Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program was one of its most successful. Within weeks, it went from feeding a handful of kids to hundreds around the Bay Area. Campbell’s sister was sending her two kids to its program at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in the Fillmore District. She suggested Campbell volunteer.

Campbell served breakfast and got to listen in on informal classes on African American history as well as a political discussions on racism. “I was learning what it meant to be socially conscious, along with the children and their parents,” Campbell said.

Working with the Black Panthers gave her a strong sense of community and personal strength, she said. “I understood the Panthers’ mission of setting up social programs in the community because my grandmother was an evangelist, a traveling preacher who taught me that you help people.”

Campbell had never been out of the Bay Area when she left for Miami. She was born in Sacramento, where her grandmother was well-established and owned several houses. The family later moved into a three-story house in San Francisco, where “I felt safe and protected.” She attended Polytechnic High School, which was more than 50 percent African American and Filipino, she said.

She was looking forward to dorm life in college. Instead, she was placed in a gloomy room by herself off campus. “I was isolated and lonely,” she said. “I had no one to help me navigate school life and culture.”

In her short time there, she also was rattled by two approaches by strange men. Once, as she was about to enter a restaurant, a car drove up next to her; its driver, a black man holding a gun, said he’d wait for her to come out. Frightened, she convinced a black couple in the restaurant to drive her back to campus.

Confronting the southern legacy

Another time, a white man approached her on a football field she crossed to get home, offering to take her out to dinner. She said no; luckily, he didn’t persist. And in an otherworldly dinner outing, a waitress at a Sambo’s restaurant approached her with painted brown face and exaggerated red lips. “It was horrid. I didn’t want her to touch my food.”

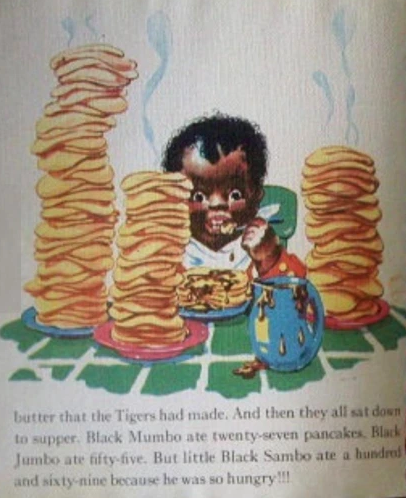

The waitress told her she was required to wear the makeup. The restaurants name was an amalgam of those of its two owner, but they made promotional hay of a similarly named children’s book, “The Story of Little Black Sambo,’ whose character loves pancakes.

Lost in the jungle, Sambo is chased by tigers who circle him around a tree. But they eventually melt into butter, which he puts on his pancakes.

Sambo is Indian but dark-skinned with kinky hair and wide red lips. The images the restaurant chain used were soon vilified as racist, for their nod, like other blackface characters, to a view of African Americans as simple or lazy.

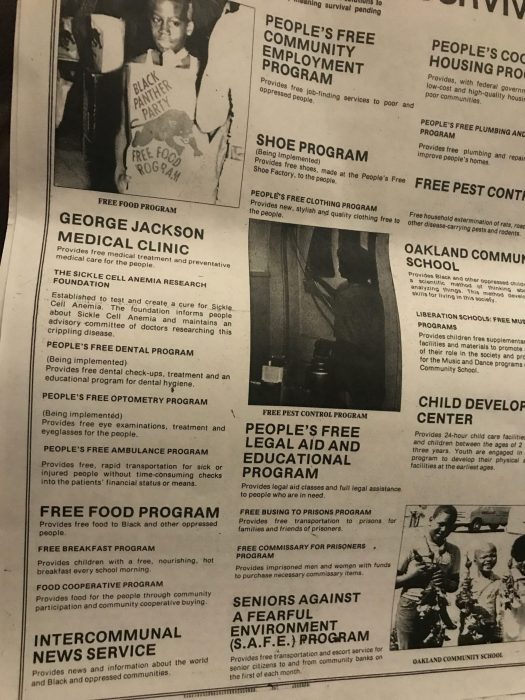

The Black Panther legacy is a mixed one, of community good but also violence. In addition to the Free Breakfast Program, they created free medical clinics, community ambulance services and legal clinics. But some openly carried weapons – as “armed citizen patrols” to monitor police behavior. Newton was alleged to have killed an officer in 1967. In 1968, Eldridge Cleaver, another Panthers’ leader, led an ambush in which two policemen were wounded and another Panther official killed. FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover viewed them as a threat and vilified them in the news.

But Campbell was more focused on the good. At its apex, the Panthers’ breakfast program got national attention by serving approximately 20,000 children in 22 chapters across the country. Some believe it encouraged the permanent authorization in 1975 of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s School Breakfast Program, which had been languishing since the mid-1960s.

“I didn’t see the word ‘militant’ in the way it was used by the FBI against the Black Panthers,” Campbell said. “I saw it as a straightforward word used to create all these survival programs to help our community.”

As a young Panthers volunteer, Campbell felt an affinity with the kids who weren’t getting breakfast before they went to school. In the two years her family lived in Palo Alto, when she was in junior high, she didn’t always get breakfast, she said, a result of family difficulties and finances. “My stomach felt like it was caved in; I couldn’t concentrate on my homework.”

Campbell married a fellow Panthers’ volunteer and moved to Toronto, but returned to San Francisco, with their daughter, after three years. “I had to stay with his family while he traveled for work and that was hard because we were just so different.”

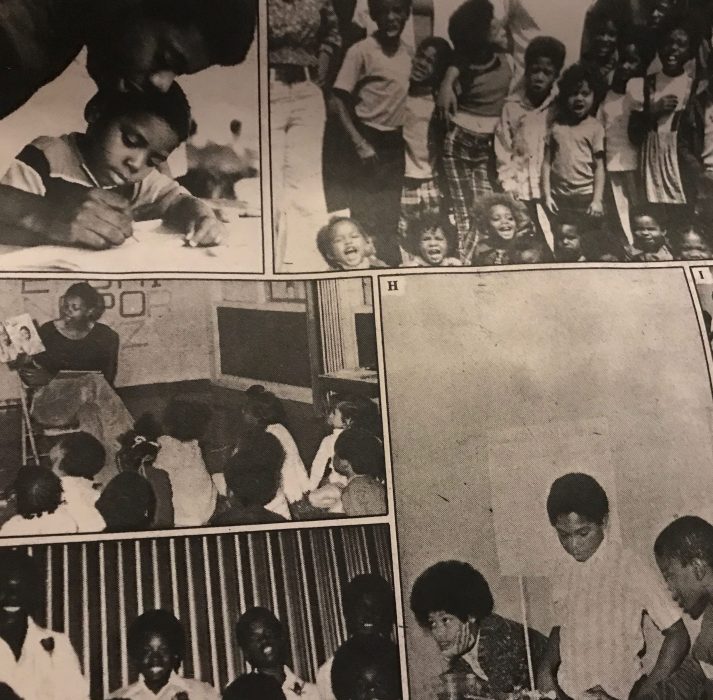

Back home, she resumed her education – courses in art and community addiction at San Francisco State – and her volunteer work with the Panthers. She became a member, which entitled her to low-cost housing. When she expressed an interest in working on the Panther Party’s newspaper, they started her out in distribution. “I went on to develop pictures and do layout for the paper,” she said.

Worries about association with Panthers

Campbell held various jobs at different city and state agencies and worked at one time as an activities coordinator for Mission Housing, she said. But finding a job was always difficult; she also spent time homeless and on welfare. She never mentioned the Panthers, which disbanded in 1982, in applying for jobs. Despite the experience she gained, she worried her association with the group would be seen in a negative light.

But in truth she was grateful for her experience with the Panthers – and still is. “What I experienced there carried over my entire life,” Campbell said. “I am very proud of that program and the work I did with it.”

In December, on what would be the Panthers’ 50th anniversary, she organized a celebration to show her appreciation. She hosted children from the John Muir Elementary School, her alma mater, at the skating rink on Fillmore Street, where Sacred Heart once stood. “We fed children the same breakfast the kids ate years ago: eggs, bacon, bread, grits and orange juice.”

“I didn’t see the word ‘militant’ in the way it was used by the FBI against the Black Panthers. I saw it as a straightforward word used to create all these survival programs to help our community.”

Katherine Campbell

In 2010, at the age of 60, she got a good job as an addiction case manager for the state. Unfortunately, she was there only four years. She ended up on permanent disability after being hit by a car while bicycling to work.

Luckily, she had continued her studies, earning an associate degree at Laney College in art and architecture. And like her time with the Panthers, it’s helped enrich her life today. Besides seeing her daughter, who is a teacher in Marin, she paints.