Little over a decade ago while visiting Córdoba, a city on the southern coast of Spain, Peter Linenthal stopped at a small shop to buy stamps. It was an errand that changed his life.

He noticed a box filled with old coins. He bought one for just $10. It turned out to be much more than a tchotchke. It was a 2,000-year-old coin, a relic of the Kushan Empire, which ruled over a portion of central Asia near Afghanistan on one of the trade routes of the Silk Road. “I was amazed that for such a low price, you could buy a piece of ancient history that opened a window on an ancient world,” said Linenthal, a San Francisco illustrator and writer.

A book to educate and encourage children

The find sparked an interest in old coins that grew into a lifetime of collecting figurines from the region and inspired him to write an illustrated children’s book, “Jaya’s Golden Necklace.”

Jaya is a fictional tale of a Kushan girl whose parents are summoned to the royal palace by the king: her father to sculpt the first image of the Buddha, her mother to bake an apricot cake. It meant a frightening journey; to assuage Jaya’s fears, her mother gave her a necklace of golden coins.

Whimsically illustrated, the book is an introduction to an ancient culture and religion, a lesson in courage and faith. It even includes a recipe for the mother’s apricot-almond cake.

Published in 2015, “Jaya’s Golden Necklace” is one of 15 books the 68-year-old Linenthal has written or co-authored. They include a series of four board books for babies – “my best-selling work,” he says – a series called “What was it like Grandma?” in which grandmothers of different cultures tell their stories; and two books about Potrero Hill, his home for more than 40 years.

A best-selling series, with illustrations by Linenthal, exploring wisdom from many cultures.

Although he’s published thousands of words, Linenthal says: “I don’t define myself as a writer. I’m a visual artist.” If he were inclined to, he could expand that self-definition to teacher, art collector, student of religion and local historian.

Linenthal’s home, a spacious, light-filled flat is filled with hundreds of figurines from Asia and bookshelves stuffed with volumes of art and religious history. His husband, Phillip Anasovich, is a collector as well. One of the many glass cases in their flat displays a collection of 18th-century French teacups. “Some of these are older than our country,” Linenthal remarked. Another vitrine showcases Native American art of the Southwest.

From collecting to cataloging

Many of the central Asian artifacts in his collection are over 1,000 years old and show the influence of numerous cultures. There is a pronounced Greco Roman influence in some, but Linenthal, like many art historians, struggles to balance the indigenous Asian influences with the European. “It’s a complex question,” he said.

Because he is fascinated by local history, Linenthal frequents construction sites, looking for hidden neighborhood relics. While chatting with a visitor, he displayed a California license plate from 1920, a weathered metal sign touting Farmers Insurance, and bits of wallpaper wrapped in advertisements from a newspaper that appears to date from the early part of the 20th century.

Linenthal directs the Potrero Hill Archives Project, started in 1986 to collect oral histories and anything connected to the neighborhood’s history. The project sponsors a yearly neighborhood history night that features talks, food from local restaurants, and displays of historical photos and maps of the area. This year’s history night may be virtual. “We’ll see what’s happening in the fall, but having a large group of people together is probably not a good idea,” he said.

Linenthal leveraged his knowledge of the neighborhood into a pair of books about Potrero Hill, written with Abigail Johnston and available from Arcadia Publishing. They are currently working on a third, this one about nearby Dogpatch. There’s no date for its release, but Linenthal has been busily collecting research, which currently encompasses a pile of papers and binders about 18 inches high.

Creativity supported by writer parents

Although he grew up in Presidio Heights, Linenthal attended daycare at the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House. His teacher there, Rhoda Kellogg, worked hard to inculcate a love of art in her students, and those lessons stuck. “I was into witches and monsters,” he recalls. He’d sometimes draw on the walls of the family apartment, a habit that annoyed the landlady – but not his parents.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that his parents encouraged his creativity. Both were writers. His mother was Alice Adams, known for her short stories and novels. His father, Mark Linenthal, was a poet who taught at what was then known as San Francisco State College.

Being the son of famous writers could be challenging for some, but not for Linenthal. “No, I never felt like I was in competition with them,” he said. “They were always very encouraging,” he said.

Linenthal studied art at the San Francisco Art Institute and later at San Francisco State, where he obtained a teaching credential and taught art in the city’s public and private schools for some 30 years. “I’ve always enjoyed the art of young children,” he said, displaying a crayon drawing made by a long-ago student.

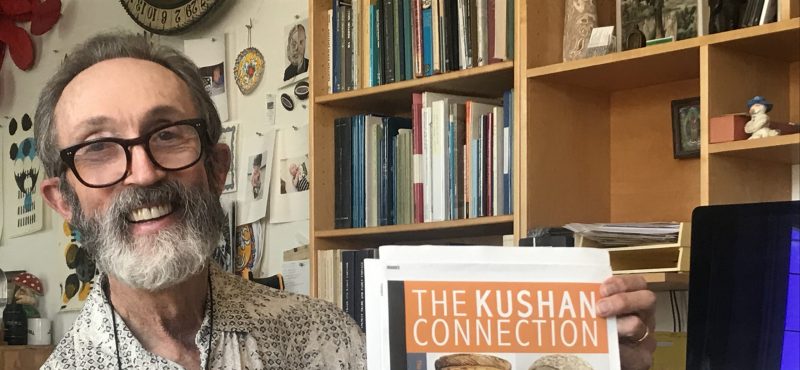

His next project? A catalog of his Asian art collection, undertaken in partnership with a German archeologist. Linenthal expects to publish the book himself and has already designed the cover. “I’m calling it ‘The Kushan Connection.’ My goal is to finish by the end of the year.”