Though one might not see a direct connection between controlling a line of punk rockers eagerly awaiting entry to the Mabuhay Gardens and running a food pantry, for Michael Reid it came in handy.

For the past 17 years, Reid, now 64, has been the operating manager of The Food Pantry at St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church on Potrero Hill. But sometime before that, he had been right in the middle of the city’s frantic punk music scene, booking his own and other touring bands. He played bass. He stage-managed at the Strand, the Warfield and the Mabuhay, a Filipino restaurant and club that became the center of New Wave and Punk with acts such as the Dead Kennedys, Devo, the Go-Go’s, Blondie, The Police, Patti Smith and more. Reid himself booked many of them.

He also wrote for Fanzine for the Blank Generation, the West Coast’s first to focus on the punk rock scene. He also led an early podcast interviewing several fanzine publishers. But along with the music scene went the drug scene and Reid burned out. He took a break to try and reinvent himself. And though he didn’t see it at the time, St. Gregory’s would show him the way.

It happened on a trip to the church to pick-up free groceries for a recently disabled friend. “I went to the pantry a couple of times and then this big green compost bin fell over and I picked it up.” Pantry Founder Sarah Miles noticed that simple bit of initiative and asked him to volunteer.

Having had some bad experiences volunteering, Reid wasn’t too eager. Then again, he said, he “didn’t have anything to do on Fridays.” He knew if he thought about it, he might not do it. So, he agreed to “help out two or three times.”

From bass to broccoli

Several weeks into the job, and based on his work at the Mabuhay, he saw a way to get people more quickly through the food giveaway line. Seeing he could make a difference, Reid was hooked.

That was 2004. A year later, he was asked to serve as operations manager and join the pantry’s newly forming board. Today, he and church Pastor Paul Fromberg are the only two original board members still serving.

Volunteering may be rewarding but it doesn’t pay the rent. So, it’s fortunate the church also hired Reid as house/site manager. That salary covered his expenses. But the pandemic forced the church to close its doors, effectively ended his job as site manager. “That put the damper on my income. Now it’s kind of a wing and a prayer. So far, I have been lucky in keeping the wolf from the door!”

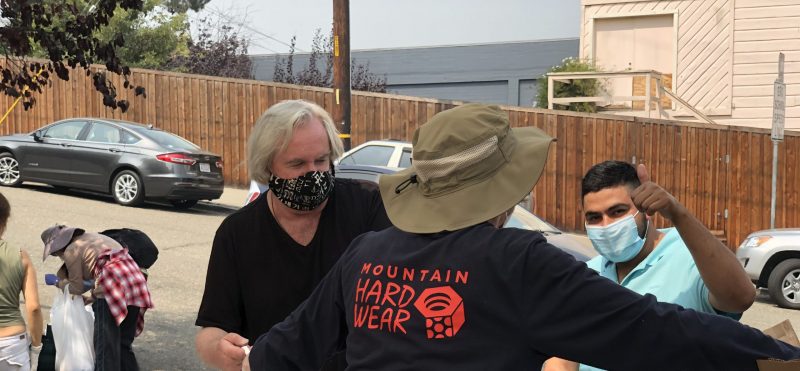

Reid is still volunteering about 20 hours a week at the church. The food pantry was moved to the church’s concrete “backyard,” he said. “We’re hoping to purchase a large tent to protect the perishable items in the warm weather and provide shelter during the rain, cold and heat.” That hasn’t happened yet, and concrete, he’s quick to say, “can really take it out of you on a hot day.”

Previously the pantry had been arranged like a farmer’s market – but indoors. People walked around selecting the items they wanted. The new set-up eliminates choice. Shoppers instead receive pre-packed 40- to 50-pound bags of food. “We encourage them, particularly seniors and pregnant women, to drive up so we can put the food in their car.”

All this lifting and hauling meant many older volunteers had to stand down. Reid now spends part of his time recruiting volunteers with stronger backs. Among them are people from Google, Salesforce and other local businesses as well as SF Together, a citywide mutual help group formed in response to Covid-19.

“A wonderful group of young people,” Reid said. “They’ve held food drives and fundraisers for us. They help us pack the groceries and clean up. I could speak volumes of praise for them.”

The biggest change for the pantry, he said, is who they serve. Pre-Covid-19, its clients were mostly Asian but they’re been reaching out to nearby Latino communities. “Many who we serve are undocumented. We don’t ask anyone to register or sign-in; we just welcome and count them.”

Despite a loss of income, Reid said he’s been refreshed by all the changes.

“The old pantry was like a well-oiled machine. We had reached a level of perfection where we really couldn’t operate any more efficiently. It was getting monotonous,” he said. “Now I’m feeling inspired.”

Before Covid, the city boasted more than 200 food pantries, including those in the schools. “Now there are only 25. What we do is significant.”

St. Gregory’s is one of the largest remaining pantries, serving more than 400 families each Saturday – unless there are rumors of an I.C.E. raid, he said. “Then our numbers drop to 200 and it takes a while for them to pick up again.”

Reid wasn’t born to run a food pantry in San Francisco. He wasn’t even born in the United States. He’s a Londoner from a working-class family who “played bass in a lot of bands, wrote about music and ran record stores. When punk started, I was right there, an eyewitness to history.” He was there at the dawn of Goth and electronic music, too.

But life in England was not easy in the 1970s. It was hard to find work. His sister had moved to Texas and suggested he join her. San Francisco was more his style he discovered after a three-week vacation here.

“San Francisco is a lot smaller than London, but it’s also closest to London musically,” he said. “The punk revolution had died in England; it was just getting started here. San Francisco was also on the cutting edge of industrial and electronic music.”

Still, it was something of a culture shock. “Everyone had a car and a color TV. We could not afford them back then in the U.K.”

For some years, music sustained him. For four years, he booked nearly all the major punk bands in the Mabuhay.

“We often pushed the limits of our crowd capacity. I also booked a lot of goth, post punk, industrial and indie bands. … sometimes I would also stage manage or work the door, not just for punk bands but for other genres like heavy metal and new wave.”

When not working, he joined small pick-up bands, playing in homes and small clubs along the West Coast from Portland to Los Angeles. “No one ever heard of us. We never put out a record and no one would remember us.”

From the outside, the music business sounds romantic, but for small bands it involves a lot of traveling to out-of-the-way venues, sleeping in trucks or on the floor in someone’s spare room, hauling and setting up equipment, and then breaking it down and packing it away. Well-known bands could afford support crews; lesser knowns didn’t have that luxury. “In 1989, I crashed and burned out of music, and other very bad habits.”

The next six years were devoted to Recovery.

By 1995, he’d gotten himself together enough to begin working construction and other short-term jobs. Along the way, he turned his love of history and particularly 19th century Japan into an expertise he poured into writing.

“I spent about 25 years studying this stuff. Not in school, on my own. I must have sat through about 500 Samurai films. When I reinvented myself, I started writing on genre films like spaghetti westerns, Italian crime and horror films, Japanese samurai and Yakuza films as well as Hong Kong cinema.” He also wrote for Japanese-themed websites and M.A.M.A., a martial arts magazine.

After being injured on a construction job, Reid decided to find work that allowed him to “sit down.” The next seven years found him at a market research firm recruiting participants for focus groups on medical products. When new ownership took over, he returned to short-term work.

But music still maintained its hold. In 2012, he and friends from the music world came together to sponsor reunions. They called themselves the Punk Rock Sewing Circle, in deference to their ages.

“We were the people who worked the clubs – photographers, booking agents – we managed bands. The last reunion held in 2015 lasted seven days. It started in the East Bay, crossed the Bay to San Francisco. We held readings at the Main Library and at galleries and the Verdi Club.”

Reid has made a life for himself in San Francisco, although he still misses England. “I’m a football fanatic, the English style. A lifelong Chelsea supporter, since the age of five. I used to go to the Stamford Bridge Stadium and travel to some away games.” He watches English football games from the comfort of his house; he has less energy, he admits, and his back hurts from his old injury.

He’s moved into a leadership role on the Japanese-themed web activities he began during Recovery, contributing film reviews to the Samurai Archives History Page and moderating its podcast on Facebook, as well as managing a private website for Kaidan Japanese ghost stories.

“Every Christmas, the BBC played ghost stories which I really liked, and there was a regular program called Mystery and Imagination.”

While music plays less of a role in his life than it did in his youth, he’s aware of the local music scene. The biggest change he’s seen since he arrived here some 40 years ago has been “the slow erosion of the live music scene over the last 10 years. It’s becoming all dj’s.”

The old days are gone, Reid concedes. Even the Punk Sewing Circle stopped having reunions. But post-Covid, he said, might just demand another one.