Like so many young people, Leigh McLellan had not clearly fixed on a career when she entered college. A course in graduate school piqued her passion for creating hand-printed books. It was a career she pursued for 15 years – before suddenly giving it up.

McLellan, like many young people, had more to discover about herself.

Heading off to the University of Mississippi agricultural school, she hoped to become a veterinarian. She had enjoyed showing her dog in “sanction shows” as a teenager, so it seemed a natural fit. But the science courses were tough and being in a mostly male class of colleagues wasn’t particularly comfortable, she said.

So, recalling her mother’s words, she switched to art. When McLellan was four, her mother had looked at her drawings and exclaimed, “My daughter is an artist!” From the wisdom of 70 years, she realizes her mother “was looking for signs of genius,” but McLellan attests her pictures were atypical for a toddler. “I drew in two dimensions. My people had shoulders, fingers, and bodies – not like the stick figures children draw at that age.”

September of her sophomore year found her pursuing an art degree at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, “a more hippyish school by southern standards.”

From poetry to hand printing

But on graduation, while working various odd jobs, instead of art she began dabbling in poetry. She gained admission to the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, where she eventually got a Master of Fine Arts degree. What excited her deepest passion was a class in typography – and its entry to the world of handmade books. She would eventually establish her own private press in San Francisco.

McLellan was born in in the early 1950s in New Orleans, La. When she was five, the family moved to Meridian, Mississippi for her father’s business. The shift from the cultural mecca of coastal New Orleans to a land-locked city centered on railroad transportation was a disruption that would have long-term impact.

Already interspersing her vocabulary with French, she never felt she belonged in Meridian. “The happiest time of my childhood was the three weeks we spent every summer with my father’s family on the bayou near New Orleans. All the families would gather. All 20 of us grandchildren were free to roam. We had a pool, speed boats, small sail boats, and horses. “

In the evenings, they would play Crazy 8s and hide-and-seek while their parents played Bridge. They were a clannish family: “We prided ourselves on our Scottish and French backgrounds.”

In many ways, the world of bookmaking – typography, hand typesetting, and printing – marked a turn not only in her career but her personal life. Perhaps reminiscent of those family summers, she found a group of people she felt were truly supportive. “We shared a common interest that was of primary importance to all of us, lending each other resources, support, and offering advice on making and selling our creations.” Her teachers also encouraged her first book of woodcuts accompanying poems by her poet friends, giving her design advice, donating the use of type and presses, book cloth, and sharing contacts at libraries and booksellers.

After graduation, she was hired to design books for the university press. It was a rewarding job, but having found the nurturing she needed, she was ready to leave the nest. She didn’t want to duplicate the path of so many of her peers, unable to leave the protective confines of the college. In 1977, two years after graduation, she set out for San Francisco.

Starting her own press

It was a relatively easy move. “San Francisco had the kind of expansiveness I wanted and I knew some of the people in the book arts community.” In 1979, she bought a Vandercook Proof Press, rented studio space South of Market with other creative types and began producing handprinted books under the name Meadow Press. She also began working as a freelance commercial book designer.

Things seemed good. “I was doing what I wanted to do, hanging out with my people. I was where I wanted to be. My hand press supported itself; commercial book design and production for large and small publishers paid the rent and groceries.”

But nine years later, by the time she turned 36, things began to fall apart. In 1990, she broke up with her “Last Boyfriend,” gave up hand printing and sold the Vandercook.

“I had taken the art as far as I could go. I didn’t want to print the same book over and over. And I was tired of being poor and worrying about what I would do if I lost my apartment,” she said, adding “I didn’t want to print books I couldn’t afford to purchase.”

A year after selling Meadow Press, in 1991, she bought a computer, her first, to support her work as a commercial book designer. “Designing is so much easier with a computer!” Switching to graphic design, she doubled her earnings.

A crisis of identity

But even as these modern tools addressed her money issues, she was still feeling uneasy on a personal level: “What am I if I’m not a letterpress printer?” she wondered. Her identity, her art and her work were interwoven – pull one thread and the whole tapestry falls apart. “I went into a tailspin; I was burnt out, dazed, depressed, and stressed. I had a nervous breakdown that no one could see. I’m good at keeping things inside.”

The thread behind the unraveling was her sexual identity.

“Coming out was a slow process. It took about 10 years for my feelings toward women to develop and for me to own it. I was still dating men.”

Therapy and a coming-out support group helped her accept that “just being me is a fine thing to be.”

In 1989, she started dating women and since has had two long-term relationships. They restored the sense of belonging and continuity she has always sought. “One of the good things about being with women is that the connection doesn’t go away. We stay friends for a long time.”

From 1999 to 2014, McLellan was a member of and at one time directed the San Francisco LGBTQ Speakers’ Bureau. She especially loved talking to kids about sexual identity, but the role also gave her “a place in the LGBTQ community.”

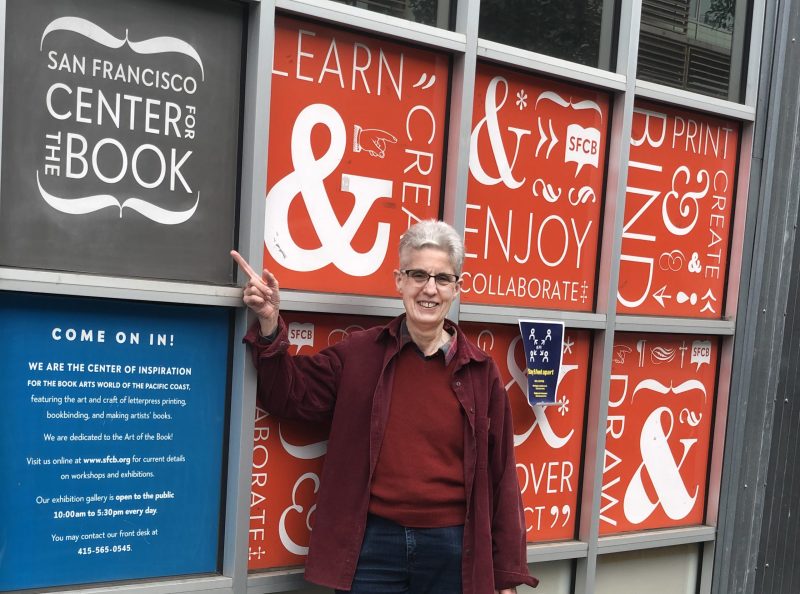

And she hasn’t lost her connection to the world of letterpress. For the past 18 years, she has taught letterpress printing and decorated papers – temporarily halted by the pandemic – at the San Francisco Center for the Book.

Back to the basics

She recently completed a three-book assignment for New Village Press in New York with another in the works, as well as books for other clients, handling the whole process, from manuscript to delivering a file suitable for the printer.

It would be easy to say McLellan finally found her career but settling into one thing is not who she is. “Life is varied, enriched when you can turn in so many directions.”

In fact, she’s returned to writing and has begun hand drawing again. She calls it “reviving her skills.”

“I haven’t drawn for 40 years and I’ve still got it.”