Former NBA star can credit talent, team-first philosophy for success from USF Dons to Knicks and Bulls to USF director job

In high school, his favorite sport was baseball. But when he watched a teammate hit a big home run over the right field fence, he knew he didn’t have that in him. He turned to basketball, grew to love the game – and reached stardom.

Over a more than 30-year career in professional basketball, Bill Cartwright helped win six National Basketball Association championships, three as a player for the Chicago Bulls then three as assistant coach. He was starting center right out of college for the New York Kicks, then traded after nine seasons to the Bulls, for whom he played another six. After one year with the Seattle Sonics, he returned to the Bulls for another six seasons as assistant coach.

Since retiring from basketball in 2014, Cartwright has been director of University Initiatives at the University of San Francisco, lured back to his alma mater by then president Fr. Paul J. Fitzgerald. His job involves fundraising and mentoring students.

A country boy makes it big

“The biggest thing I learned at USF was about possibilities,” Cartwright said. “I came from a small town, and I didn’t know you could be a CEO of a company or have your own business.”

He also owns a restaurant in Chicago and is in a partnership in a car dealership in Wisconsin. In fact, he was getting ready to open a McDonald’s franchise in 1996, after completing a master’s degree at USF in organizational development. But when Bulls General Manager Jerry Krause beseeched him to return to work as assistant coach, he couldn’t say no.

At 7-foot-1, Cartwright was built for basketball – and playing center, usually the tallest man on the team who can not only score but protect the goal. He loved playing in the days when “the center occupied the middle space and would intimidate guys flying down the lane. Now, it’s three-point shots, dunks, back-and-forth,” he said. “It stinks.”

By the age of 8, he was 6’6” and 220 pounds – big enough to drive the tractor on the family ranch in Lodi, Calif. The only boy in a family of seven children, he grew up helping his father farm corn, tomatoes and beets. “I learned about hard work and overcoming adversity dealing with those beets with the long-handled hoe,” he said.

He turned that tenacity on basketball when he played with Elk Grove High School’s Thundering Herd: He was named California’s Mr. Basketball two years in a row and selected California High School Sports Athlete of the Year. In 1975, the team captured the Tournament of Champions title at the Oakland Coliseum.

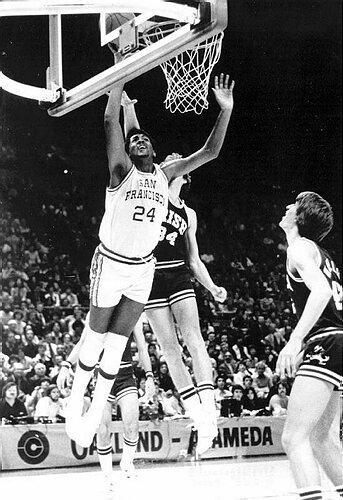

When it came time to choose among offered college scholarships, he and his parents carefully assessed coaches. USF won him over: “I really connected with the coach and the players,” he said. At USF, in one of the tallest starting lineups in collegiate history, Cartwright was named a consensus All American player in 1977 and 1979. He graduated as the all-time leading scorer for the Dons, leading USF to three NCAA tournaments.

Cartwright married his high school sweetheart, the vice-principal’s daughter, Sheri Johnson, and had three boys and a girl: Justin, Jason, James and Kristin. As he moved around in his NBA career, his family moved with him.

He went on to become the primary scorer for the Knicks. In his first season, he appeared in the NBA’s All-Star Game. The next year, he was selected for the all-rookie team and was an Eastern Conference All-Star.

The practicality of his high school switch from baseball to basketball is an example of the Cartwright method of operation: It’s not just talent that propelled him. It’s his attitude. He took trades and reassignments as all part of the job. “People knew me for this philosophy: I’ll do what’s best for the team,” he said.

“Bill was one of the nicest and humblest people I ever met,” said Dan Rigley, his Elk Grove coach. His USF coach, Bob Gaillard said, “He looked you in the eye, wanted to learn and realize his potential, and he was humble.”

A thick skin comes in handy

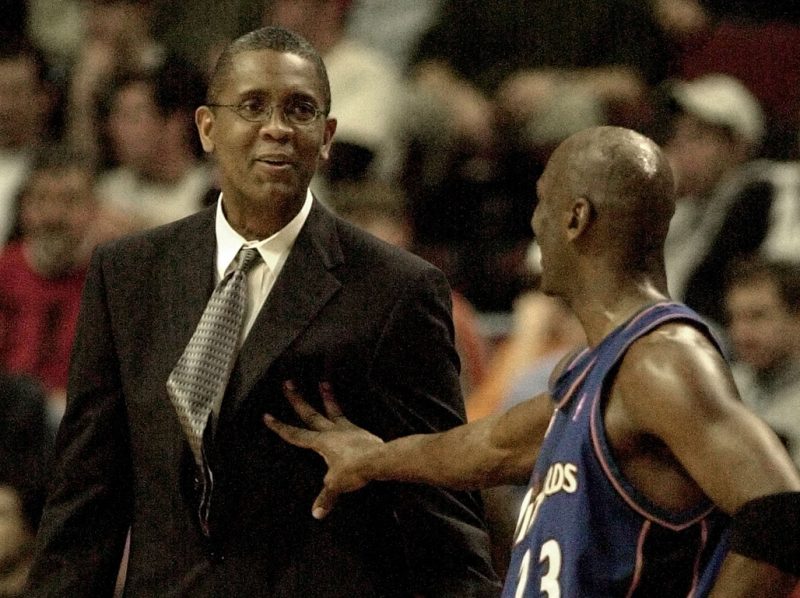

His choice of sociology as his college major was no accident and helped set him up for his later coaching years. He called himself an “observer,” and said “with observation comes thinking, and sports is thinking.” Coaching for the Bulls required studying and reporting on nine teams. “Coaching is a great mental exercise. It is really teaching, and not everyone can teach.”

Coaches were harsher in his day, he said, and he liked it because he knew where he stood. “I owe my success to the great coaches on the Knicks – William “Red” Holzman and Hubie Brown.” And he found his greatest mentor, he said, in Bulls assistant coach Morice Fredrick “Tex” Winter.

The New York media was also a tough critic. “You saw on the back page of ‘The Post’ how you were playing – good or bad. I had to ignore the noise and do what I believed was the correct thing,” he said. “I had to learn to be really secure inside myself, have a positive mind-set and be my biggest fan.”

He never missed a game but in his third year, he stepped on a rock during a workout. He kept on running, causing a stress fracture in his foot. “I played on it, injured it, came back the next year and it broke,” he said. That sidelined him for a year and a half.

While he was out, the Knicks drafted Georgetown University star center Patrick Ewing. And when Cartwright came back in 1987, he was relegated to the bench more and more. “My minutes playing grew less and less,” he said, “and I was prepared to be traded.”

Benched then traded

And he was. When he joined the Bulls the next season, Cartwright admits, “I was 31, the old guy, the adult in the room,” on a team he called “young and inspiring, always ready to go.” Not everyone welcomed him, particularly Michael Jordon, whose friend and teammate power forward Charles Oakley, was the other half of the trade. Still, Cartwright didn’t let it bother him. “Nothing is going to bother you after playing in New York” he said. “I was there to do a job and I meant to do it.”

The Bulls had been whipped by the Detroit Pistons for two years. That changed, Cartwright said, when Phil Jackson came on as head coach for the 1989-1990 season and Michael Jordan started making big scores. Cartwright’s role changed, too, to defense. “They didn’t need me to score and I was okay with that. To win, you have to understand and accept your role, and play it as best you can.”

Cartwright was in the starting line-up in the 1988-89 season and the team made it all the way to the Eastern Conference Finals. The next season, the Bulls charged past the Pistons to take out the Magic Johnson-led Los Angeles Lakers for the NBA championship. Cartwright was the Bulls’ starting center for their next two championship games, in 1992 and 1993.

It wasn’t until 1994 that the man who took so many changes in his own career in stride first allowed himself an explosion of anger – at someone refusing to be the team player he had always been. The Bulls were trailing in the Eastern Conference Semi-Finals against the Knicks when on the most crucial play of the Bulls season to that point, the coach asked Scottie Pippen, usually a forward, to assume the role of in-bounder – a decoy. Pippen refused and sat on the bench.

‘Basketball is personal’

The Bulls won the game – by a point – but the usually even-tempered Cartwright was furious. He gave Pippen a dressing-down in the locker room in front of his teammates. He saw it as his responsibility as a senior member of the team. “Basketball is personal. It’s what you do. It’s who you are,” he said. “I’m not going to lose a game because of someone’s ego.”

When Cartwright’s contract ran out, he became a free agent and signed with the Seattle Supersonics. But he retired after the 1994-1995 season, at the age of 38. “I couldn’t run as fast as I used to. My body told me to stop.”

He ended his run with the Bulls in 2004, as head coach. He continued coaching for NBA teams the New Jersey Nets and the Phoenix Suns as well as a top team in Japan and the Mexican National Basketball Team.

Looking toward a final retirement, Cartwright doesn’t see only fishing in the picture, as do some of his buddies. “Right now, I’m working on my memoir, thinking of something seniors can do, and entertaining doing podcasts.”