‘It takes the hood to save the hood’ – with plenty of push from local Latin jazz icon and ‘mayor’ of the Mission District

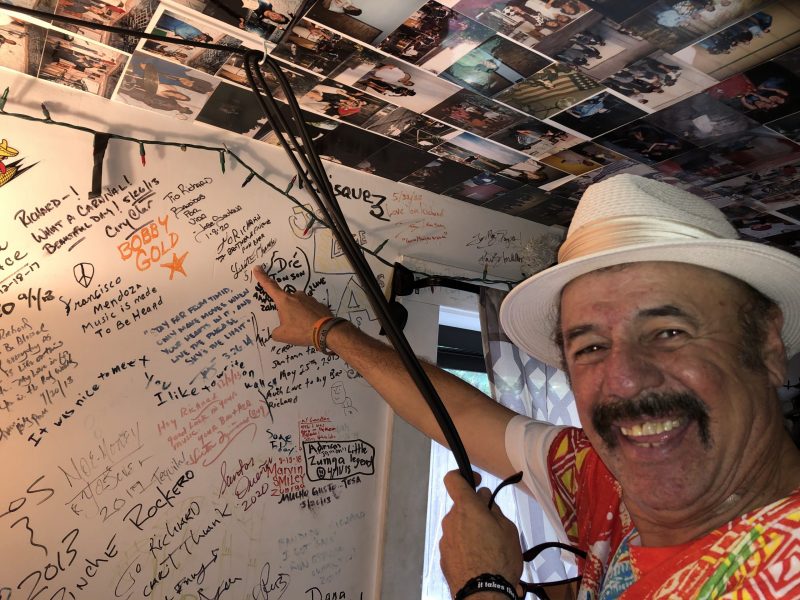

Tourists from around the world gape at Richard Segovia’s house. A kaleidoscope of vibrant colors framing the portraits of local Latin rock musicians weave around the corner of 25th and York streets. Locally, it’s known as the “Latin Rock House,” a tribute to the genre’s birth in the Mission District.

Bay area legend and Mission district local Carlos Santana introduced Latin rock to the world. By the start of the ’70s, Santana was joined by a host of local bands and performers who fed the country’s hunger for the new sound that crossed all boundaries. Segovia’s house, inside and out, is a chronicle of that movement.

Leading a tour around the exterior, Segovia points to portraits of local music legends like Santana, Malo, the Escovedos, Malibu, Able and the Prophets, the Filipino Latin Rock bands Don Quillo and Sapo, his own band Puro Bandido and so many others. “The Mission District is to Latin Rock what Detroit is to Motown,” he wants you to know.

But while he enjoys the hordes of outside tourists, Segovia wants the house to serve as an inspiration to young Mission District musicians.

From battle of the barrio to battle of bands

Before Santana, the Mission was not a good place to be, he said. “Gangs were fighting one another; the streets weren’t safe. When Santana’s music became popular, it went from the battle of the barrio, with knives and guns, to the battle of the bands.

“We competed with our music. That music saved the Mission,” he said. “We need to honor it.” The music gave “hard ass” kids like Segovia and his buddies an opportunity to shine.

Latin rock changed the Mission from a neighborhood avoided by outsiders to the “happening” center of the city. The throbbing music scene fueled by up-and-coming bands attracted young and old. Dancing in the clubs and in the streets replaced what had been a dangerous street scene. Young Mission-district musicians competed peacefully, if noisily, for crowds. Emblazoned on the mural the envelopes his house is the credo Segovia lives by, “It takes the hood to save the hood.”

The mural was painted several years ago by the Urban Youth Arts Program, a project of Precita Eyes Muralists Association under a grant from the California Arts Commission. It was Segovia’s idea – a tribute to the many musicians who had come to his house to record and hang out, and, he hoped, an inspiration to youth unaware of that history. “The mural keeps our legacy and our music alive.”

Invoking the Mission’s musical heritage is only part of how Segovia cares for his community. For the past 20 years, “Tio Richard,” as he’s known to his young neighbors, has offered free music lessons to neighborhood youth and recorded their albums in the same garage studio graced by the bands celebrated on the mural. He has also served as manager for new groups trying to gain a foothold in the Bay Area music scene.

But the neighborhood Segovia wants to preserve has changed since his youth. Gentrification is taking over. Young techies, who can afford the high rents and prices of Mission District real estate are moving in and changing the neighborhood. In under 20 years, it has gone from being 50 to 37 percent Latino.

Mission culture slipping away

“We’re losing our people and our culture. The Day of the Dead and Carnaval have become commercial holidays. When will it stop? The city is becoming Babylon, selling anything it can. We need to get out there and make a change.”

Change requires not only an awakening but action. Which is where politics comes in. In the months before the election, Segovia turned to Hillary Ronen’s office to help set up a voter registration table outside his home and recruited his neighbors to staff the booth. He had a table and voter forms ready. Then the fires began.

The bad air drove Segovia, a cancer survivor who lives with asthma and bronchitis, inside. By the time the weather changed, voter registration was nearing an end. While he still encouraged people to vote, the table and the drive never happened, though neighbors still stopped by to pick up registration forms and discuss the election.

This wasn’t the first time he’s organized the community.

His daughter Cassandra was only five in 1993, when Petaluma 12-year-old Polly Klass was abducted and later found murdered. News that riveted the Bay Area made its way to his daughter. She asked her dad to buy 50 balloons and drive to the spot where Polly had been found (near Cloverdale). As Segovia filled and tied the balloons, his daughter gently released them. “They’re going to Polly in the sky,” she said.

His mission is the Mission youth

That incident inspired him to contact the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. With that organization’s permission, Segovia modified its child-safety curriculum to incorporate music and brought in neighborhood youth as trainers and musicians.

“We’d share two lessons and then teach the kids some dance steps. They loved it and so did the schools.” He points to a letter from the principal at Flynn Elementary recounting how the training saved a young student who had been approached walking home. “Thanks to his training, the child knew what to do: scream and run.”

Segovia presented the program in 1994 and 2006 and now, as a great grandfather, he’s getting ready to try it again.

Then there’s his work with Rudy Corpuz from United Playaz, a delinquency prevention program, and their gun buy-back program. “I was a hard-ass kid always getting into trouble. It’s my turn to pay back.”

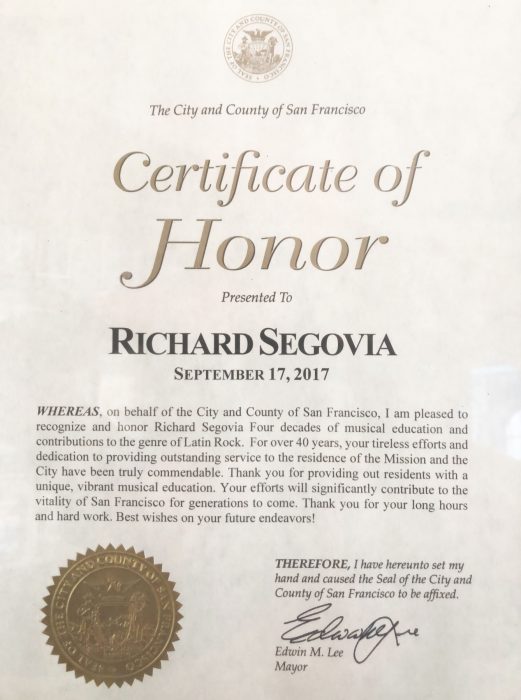

Inside the house, on a wall filled with photos of bands, letters from people he’s impacted and awards, Segovia proudly points to a 2017 proclamation from Mayor Ed Lee declaring him “the Mayor of the Mission,” and making Sept. 17 Richard Segovia Day. My calling is to take care of everyone in the Mission. I’m a connector, I’m here to help my neighbors.”

Segovia was born in 1953 in the Mission. When he was 10, his family bought the home that became the shrine to Latin Rock. After graduating from John O’Connell High School in auto mechanics, he began helping his uncle on small home repair jobs and hanging around bands after hours.

When a local band local needed a percussionist, he taught himself to play the timbales. “Only I did it backwards,” he laughed. He had lined up the two shallow drums opposite of the standard high-low set up, . Two years later, a friend pointed out his mistake, which he quickly corrected. In 1979, he joined Puro Bandido. He and the band still perform and tour.

“I’ve been blessed. I’ve been in music for over 40 years. I’ve performed all over the world.” Last year, the band played to a sold-out crowd for their 40th anniversary celebration at Club Fox in Redwood City.