Power comes from doing for others, says Fillmore native who helped bring technology training to Black youth and communities

“Power,” said Chester Williams, “is in relationships and what you can do for others. I flourish by what I do for others.” It’s a lesson he learned from his parents and is one he still strives to live by.

Over the years, the multi-talented Williams has opened many doors for San Francisco’s Black community. As a public school teacher, he sought to “present a positive role model to Black youth in predominantly white school systems.” An early convert to the possibilities of computers, he devoted years to bringing the technology to minority communities.

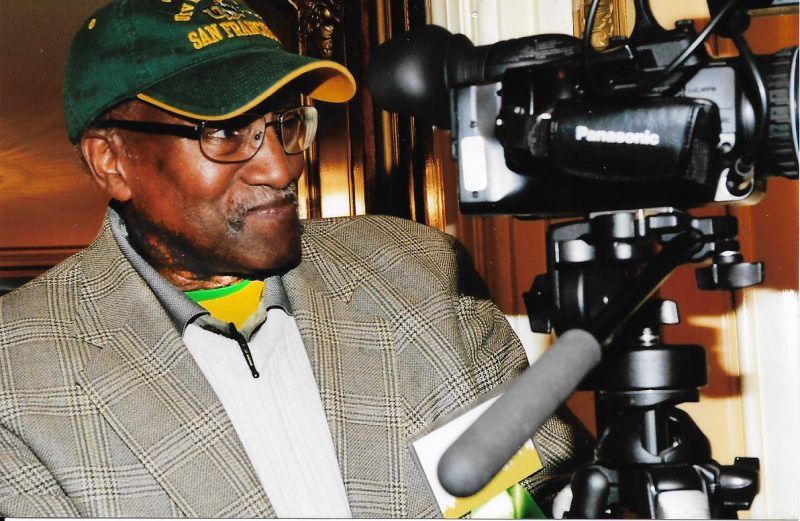

Also interested in media, he took Columbia School of Broadcasting courses in San Francisco in the late ’70s, and from there went on to start his own company, Fillmore Media Systems & Services, to film community events and funerals.

Most recently, he has been coordinating the Community Living Campaign’s grocery delivery and computer training programs for seniors in the Bayview. When there’s a need, he wants to be there, ready to contribute, ready to open doors.

“It’s what we do for others: the doors we open, the people we help,” Williams said.

Williams, now 71, was born in the Fillmore, then the city’s largest African American community. The Fillmore was a happening neighborhood in his youth, in the days before urban renewal destroyed it. Dubbed the “Harlem of the West,” music was everywhere and on weekends Williams, who played the sax and clarinet, enjoyed the music scene. For a time, he contemplated life as a professional musician.

Banding together in the Great Migration

Natives of New Orleans, his parents were part of the Great Migration, the exodus of African Americans from the South to the North, Midwest and West after World War I. They bought a home in Vallejo to be near his father’s job as a rigger at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard. Ten years later, they bought a fixer-upper in the Fillmore.

With the help of friends, their home was soon made ready for boarders. “Anybody coming to the City needs a place to stay. We always had people living with us. Black people hung together and helped one another.” It was a good life, Williams recalled. “We never had a lot, but I never felt poor.”

A strong student, Williams attended St. Dominic’s Elementary School and Sacred Heart High School. Upon graduation, the bandleader convinced him to direct the band. He did that for about a year before entering the University of San Francisco on a partial scholarship. He graduated in 1972 with a degree in sociology and education and began teaching in the public schools.

“I went into the schools to give young Black kids a positive role model. Young Black students needed to see themselves in leadership positions. They needed to see what they could be,” he said. Williams taught fourth and sixth grades in the San Francisco and Los Angeles public schools.

In Los Angeles, Williams entered a Rand Corporation program aimed at preparing teachers to use computers in their classrooms. While many of his peers questioned the value of the technology, Williams saw the wave of the future. He also decided it was time for a career change.

He had never intended to make teaching a lifetime job, and 15 years after entering the public school system, he retired. “The schools were never going to change,” he said. The education system needs to provide an education to Black students that’s as good as what’s given to white students, a process that would likely take longer than he cared to wait, Williams said.

Jesse Jackson and Silicon Valley

His talents in teaching and now in technology opened many doors. When a friend opened a software store in San Leandro, Williams developed lesson plans to teach employees at minority-owned businesses how to use the software. Another friend recruited him to teach in the after-school program at San Francisco’s McAteer High School. And then there were friends and friends of friends who needed tech help.

All the while, Williams continued taking online business courses from Walden University in Baltimore, developing the skills he knew he would need to become a successful entrepreneur.

In 2014, Jesse Jackson arrived in the Bay Area and as Williams described it, “I had the chance to do something totally unusual in the Fillmore.” Williams was among 25 Bay Area minority leaders Jackson gathered to meet with representatives of Silicon Valley’s large tech firms. Jackson understood the potential of technology to shape the future and wanted to make sure minority communities were not left out.

The group held about 10 meetings with Silicon Valley leaders. “This was not a plea for jobs or training; this was a big picture conversation looking at what the future held,” Williams said. “I decided this is a big picture I wanted to be part of.”

The San Francisco members decided to open a computer training lab in Hayes Valley/Fillmore. Money followed — $4 million from San Francisco’s Rec and Park Department and other city agencies.The grants funded the Western Addition Technology Center, which Williams ran for several years until funding dried up and it closed.

From the Fillmore to the Bayview

While others walked away, Williams was not ready to give up, not when so many in the Black community were missing out on the computer revolution. This time, though, he wanted to bring computer training to the Bayview. “The Fillmore had become so integrated it had a different feeling,” he said.

Williams set about gaining buy-in from the ministers in the Bayview, necessary for receiving funding. But they were unconvinced, and the funding never came through. However, while looking for allies, he met Deloris McGee with the Community Living Campaign’s food delivery program. McGee was looking for a coordinator for the grocery delivery program for seniors in the Bayview. Williams stepped up and was hired.

The program was extensive and Williams quickly realized that a large coterie of volunteers was needed to pack and deliver the groceries. For help, he turned to a group of neighborhood men who were part of an informal network that provided services like visiting shut-ins, helping with grocery shopping, and offering rides to appointments.

“We were initially suspicious,” explained Ronald James, one of the members. “We had been raised up around one another in the Bayview. His being an outsider from the Fillmore, it took us a while to accept Chester.” But before long, they realized “he had some smart answers and a heart like the rest of us,” said James. Today, thanks to their involvement and the support of other volunteers, the program has expanded to 127 Bayview seniors.

When Williams isn’t working, he’s encouraging youngsters to pursue their music education, even performing publicly with them when they need someone on the sax, clarinet, or keyboard. His life is better, he said, when he’s sharing what he knows and helping make life better for others. It’s a lesson he learned growing up.