Retired psychiatric nurse with a yen for drama ponders the future with humor

Susan Evans doesn’t remember when she first began using humor to deal with the “hard stuff,” but she’s counting on “the great healer” to help her through the aging process.

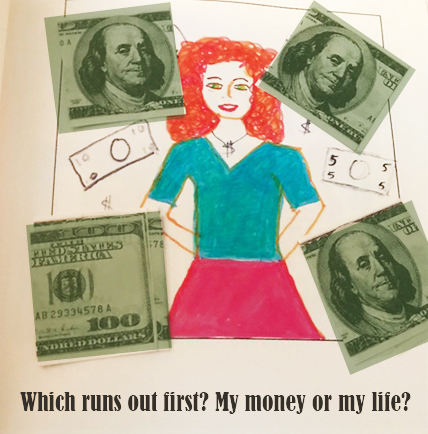

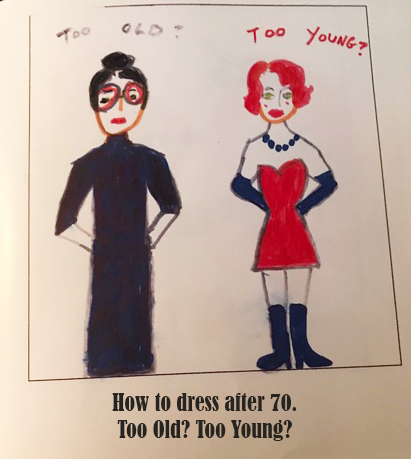

“A major one is wondering what will give out first – my money or my life?” she joked. There are lesser issues as well. “What’s appropriate dress for an older woman who doesn’t feel her age?”

Evans has been an artist and photographer, a playwright and actor. Most of her theatre pieces, humorous takes life’s quandries, have been fueled by stories from her career as a psychiatric nurse: the drug addict who will give it all up someday – but not now; the transgender man who equates happiness with a D cup; the numbing experience of working for a health insurance company.

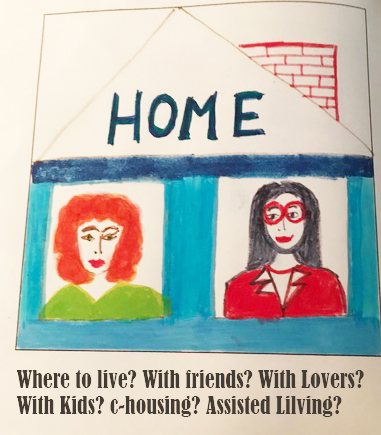

But it’s the piece she wrote with acting partner Marleen Smith and performed at the Monday Night Marsh in 2017, that has been hitting closer to home lately. She turns 79 this year. In “100 is the new 80,” she takes on some of the imponderables of aging: Do I have enough money to retire? Where do I want to live? How do I find friends at this stage of my life? Am I happy without a significant other or do I have the energy to build a new relationship? How can I find a meaningful way to contribute to society? And many others, from learning how to grandparent, how to dress and what to eat to the importance of exercising.

She doesn’t have all the answers, but she knows these issues must be approached with humor. “Have you seen the new Medicare Advantage booklet?,” she asked. “Twenty-seven options. Even when I was younger, I couldn’t make sense of 27 options.”

Evans was born in 1942 in New Haven, Conn. Her father was a salesman; her mother stayed home to raise Susan and her younger brother. As a youngster, she wrote and performed plays for her family and neighbors. One involved a bride, played by Evans, of course. The bride was supposed to appear at the end of the play, only Evans so loved the wedding gown she created from an old curtain, she rewrote the play so the bride was always onstage.

At 14, Evans began volunteering at Grace New Haven Hospital, the local hospital. “I was intrigued by the drama of hospitals. There are so many stories.” It’s not as though she came from a family of doctors and nurses, or that she or the members of her family spent time in hospitals. She just craved drama.

Access to other’s lives

Evans doesn’t remember exactly what she did after donning the pink-and-white uniform of a candy striper – probably deliver flowers and mail – but she was hooked. “It allowed me to access lives I wouldn’t have access to otherwise.” At 16, when she was old enough to work, the hospital hired her as a nurse’s aide.

After two years at Boston’s Emerson College, a school specializing in theater arts and communications, Evans transferred to Columbia University’s School of Nursing. “We were immediately put to work in a hospital. I loved it.” She continued her education at the University of Pennsylvania, earning a Master’s of Science in psychiatric nursing in 1967.

“Maybe it was my unconscious way to figure out about my family,” she mused. “I was fascinated by psychiatry. It was definitely the theatre of the absurd.”

In 1962, she and her husband, a doctor, moved to San Francisco for his post at a public health hospital. When his assignment was up two years later, they decided to stay.

In between raising two children, Evans held various nursing jobs: head nurse at St. Luke’s Hospital, HIV Services Nurse Coordinator at the Larkin Street Youth Center, and homecare nurse at Crossroads Home Health and Hospice. When she no longer had the energy to work with patients, she took a corporate position as a care advocate at United Behavioral Health in San Francisco. Ten years later she retired.

An urge to help children

Retirement opened new opportunities and allowed her to spend more time with young children. “I’ve always loved being with young children, before they’ve been tampered with too much by society and their family.” She had seen so many horror stories in her work she wanted to show them “other ways to address their anger.”

When the Boys and Girls Club asked if she would teach a health and nutrition class, she eagerly accepted. Lessons were imparted naturally during conversations over food, and her roasted carrots proved a real hit. So much so that Evans decided to try her hand at starting a business.

Developing the curriculum and recipes for “Vegelante” was not difficult, but the uniqueness of the project rested on her choice of a mascot: giant carrot plush toys she hoped the children could take to bed instead of a teddy bear. Even with a decent price from an overseas factory, the cost of the stuffies nixed the project. It made it seem like “a rich person’s thing,” said Evans, an identification she didn’t feel comfortable with.

The pandemic has limited her options. Public schools and programs shut down, the Marsh’s Monday Night Performances and classes were put on hold, and only some of her friends feel comfortable meeting outside for a walk.

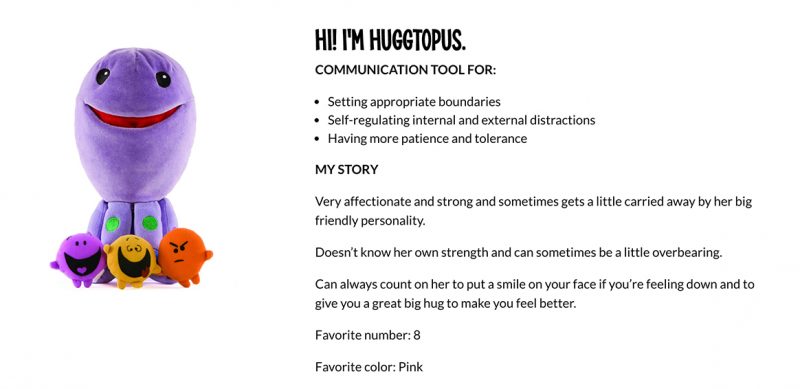

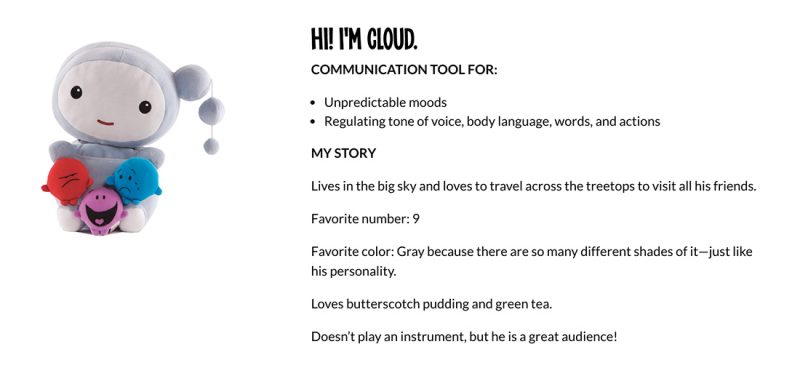

She joined the San Francisco Village and made new friends. A weekly writing group provides ongoing support, as do calls from family and friends. Before the pandemic, she had heard about Kimochis, puppets used to teach emotional intelligence in an educational program developed in Japan. She’s taken some coursework and is preparing herself to facilitate sessions when schools reopen. “There’s so much information on promoting physical health, but little on disease prevention in the mental health area. I want to be involved in that,” she said.

But two big decisions lie ahead, both explored in “100 is the new 80”: Whether to start a new relationship and whether to move.

A 12-year partnership has ended and she wonders if she has the energy to try again. Then there’s her home. Evans lives near the California Pacific Medical Center, which is planning a major, multi-year demolition and construction project. She knows the noise and traffic will be impossible. Is it time to move?

Where others might mourn the losses, for Evans they represent the prospect of adventure. Her daughter lived with her for a year when she was deciding if she wanted to live in San Francisco. “She’s in Berlin now and loves it. I told her I just might move in with her and start over.”