From the jungles of Bolivia to On Lok Senior Center, social justice advocate promotes nutritious meals and healthy programs

The knowledge was hard-won, but over the years Valorie Villela discovered the link between nutrition, health and survival. Villela struggled with bulimia from her teens to her 20s. Painful as it was, her conquest of the disorder put her on a path of service and adventure that took her from her native Oregon to the jungles of South America to San Francisco’s Mission District.

She worked on world hunger projects in college, taught nutrition to Bolivian mothers, and was part of a group that protected a Baptist pastor from a Salvadoran death squad.

Villela, 67, is now the director of Well Senior Program Development for On Lok, where she has worked to deliver better nutrition and health to San Francisco seniors for 34 years.

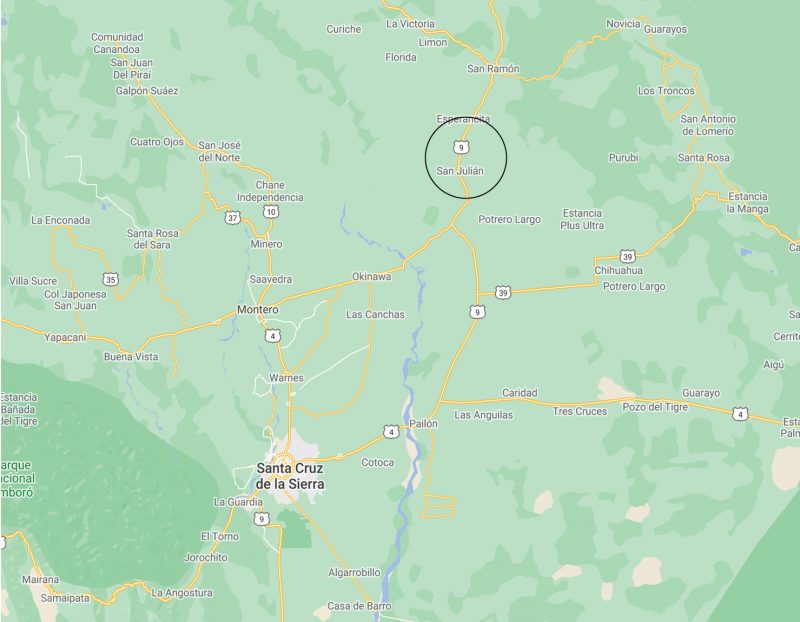

Villela was well on her way to a life of service by the time she was 25. She had served three years with the Mennonite Central Committee in the jungles of San Julián, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. She was a volunteer, working under the auspices of a U.S. AID project to teach mothers better nutrition. Volunteers saw children with extended stomachs and hair turning blonde because of a protein deficiency called kwashiorkor, a widespread problem.

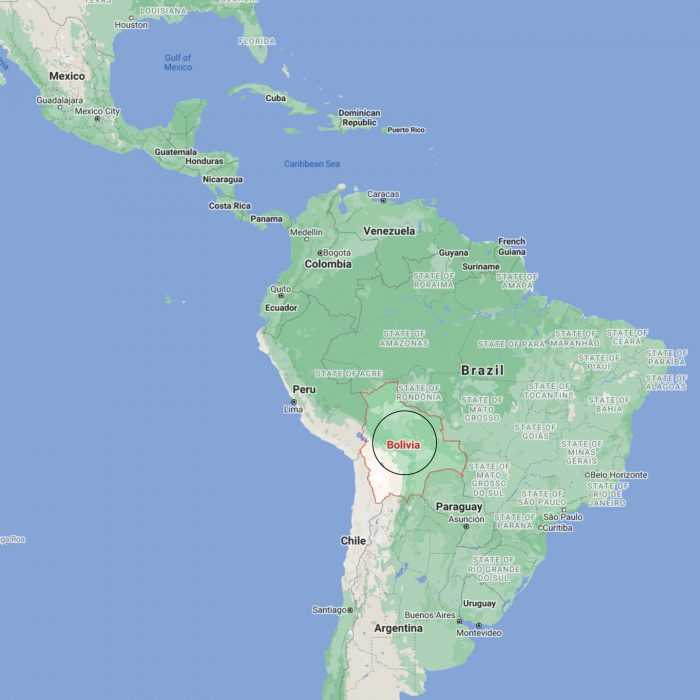

Villela is not Mennonite, but the Church was reaching beyond its borders into collegiate settings to find young people to work in Brazil or Bolivia in agriculture, nursing and health. Villela chose Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, where malnutrition was severe.

Villela knew about inequalities in world food consumption. Her undergraduate degree was in nutrition and food science from Whitworth College in Spokane, Wash. And she wanted to make a difference. Her mentorship by the “futurist” college president, Dr. Edward Lindaman, who headed the humanitarian project “Nutrition 1985,” deepened her commitment to social justice and liberation theology.

‘An oddity to behold’

Villela arrived in Bolivia “an oddity to behold,” she said. A week before her departure, she had injured her knee in a volleyball face-off. “I was the tall blonde hobbling around on crutches who had yet to learn the language of the people I was to serve. Before heading to the jungle, she spent her first three months in Santa Cruz, living with a Bolivian family and learning Spanish.

But once in the jungle where she was first assigned, she discovered a sharp divide between wanting to do good and doing good. She didn’t speak their indigenous language. “I found it difficult to form trust relationships with the women,” she said. “I had to have a Spanish-speaking person translate what I was saying into Quechua. So much was lost in translation.

“They found me interesting and were curious about what I was showing them. Ultimately, I don’t know if any of them went back to their homes to repeat the recipes.”

She fared better later in another location where the women spoke Spanish. “I was welcomed and often invited to the women’s homes for meals. But again, I was the ‘gringa’ coming to show them how to provide better nutrition; they would nod in agreement but putting my lessons into practice was another challenge. All in all, the families were poor; if they had meat at all, the man of the house always got the lion’s share and the children would get very little protein.”

She taught them how to make protein-rich meals using ingredients on hand.

Villela’s commitment to nutritional equality was rooted in her own experience. Her parents divorced when she was just 13 and she soon developed bulimia, becoming addicted to bingeing and purging food. She struggled with the disorder until she was in her 20s.

After her stint in Bolivia, Villela returned to her hometown of Portland, Ore., where she wondered “what’s next?” The Mennonite Central Committee had given her their “resettlement” payment of $300. She was, she said, on the cusp between “broke” and “flat broke.” She fretted about this as she boarded a Greyhound bus headed for Seattle, where she was going to visit friends and hunt for a job.

Divine intervention

This was the moment she calls “divine intervention.” She snatched the last seat on the bus and sat next to a kindly looking, white-haired woman who asked Villela about her plans. Her seatmate was Lois Hoskins, chair of San Francisco City College’s Consumer Education Department. They connected: Hoskins own daughter was a graduate of Whitworth, Villela was fluent in Spanish and her volunteerism was impressive. Hoskins eventually offered her a part-time teaching job.

But needing full-time employment, she was referred to the 30th Street Senior Center. She was hired as a nutritionist, a job that involved the daily preparation of about 150 meals along with menu planning and purchasing. At that time, about 70% of the clients were Latino, so Villela’s language skill was a plus. She accepted the offer and moved to San Francisco in 1981.

But her international efforts weren’t over.

As a representative of the 7th Avenue Presbyterian Church (a sanctuary church), she traveled to El Salvador in 1985 as a part of an ecumenical group to support a Baptist pastor being threatened by Salvadoran death squads for giving food, water, and supplies to the local population.

“As a result of our presence,” Villela said, “the death squads left this pastor alone—he continued his mission – unharmed, even after we left.”

In 1987 she was named director of the senior center, and in 2019 under On Lok management, she became director of Well Senior Program, researching, planning, launching and maintaining programs. The change has been bittersweet, she said. “It’s the practical visionary role, investigating the possibilities for the greater good for the active older adult and I like that.” But she said she misses the day-to-day interaction with seniors and speaking Spanish every day.

Villela has played a key role in “Mission Nutrition,” a project that delivers meals to nearly 3,000 low-income, diverse San Francisco seniors. It was, she said, a successful step in promoting public awareness of food insecurity among older adults— especially during COVID.

A matter of balance

“Nutrition is the most basic requirement for survival, strength and good health,” said Villela. “This program is one of the last buffers between independent living and institutionalized care.”

Villela and her team also support On Lok’s Always Active fitness program, which operates in 21 sites around San Francisco. Since the COVID shutdown, in February 2020, it has been adjusted, using ZOOM to reach hundreds almost every day.

“I, like many others, now work remotely from my Noe Valley residence,” Villela said. “I had to learn how to deliver classes via ZOOM. “

At first, she held nutrition and health conversations with about 15 seniors. In January, she and On Lok launched the Aging Mastery Program, a curriculum developed by the National Council on Aging that addresses key issues for adults.

While the COVID shutdown has in some ways expanded her ability to reach seniors, it has afforded her a bit more balance in her own life. She takes pleasure in quiet time with her husband or hiking with him along the trails on Mt. Tamalpais and Point Reyes.

“I keep the concept of balance in mind. If one area of our life is out of balance, the whole is affected,” she said. “Focusing all one’s energy on physical exercise while not feeding one’s emotional connections; being obsessed with the most nutritious diet and not paying attention to our spiritual hunger; or dedicating oneself to self-improvement, mediation and spiritual exercise while ignoring the world around us … will keep us occupied but eventually we feel empty and still hungry.”