Child of Jim Crow era finds opportunities, advancement, protection ‘from the outside world’ in the U.S. Army

Hunger is something Lavern Simon is familiar with. Not for food but for learning.

Born into a segregated Washington D.C., her education was less than inspiring. Her school had few resources. You had to bring your own pencil to school or pay for one, she said. Children went home for lunch each day. Reading lessons from “Dick and Jane” or “See Spot Run” came in random shuffles of mimeographed sheets – never a complete text. There was corporal punishment if you misbehaved.

Her world was small – and all black. She had little contact with white people. Until she entered an integrated school in New York at the age of eight, she said she imagined white children as aliens from another planet.

The family move to Brooklyn in 1955 launched her love affair with learning. Her new school had all the resources her previous one lacked. She did well and set her sights on college. Seven years after graduating from high school, she joined the Army because of its generous education benefits.

Loving the Army life

She planned to stay for four years; it turned out to be 18. The Army provided experiences, education, travel and a lifestyle that suited her, as well as a full career and secure retirement.

“I loved the army way of life. Meeting new soldiers, some I liked and some I didn’t,” she said. “I loved moving around from the U.S. to Europe twice, traveling around within Europe, learning a new language, and just being me in a very conservative environment that was protected from the outside world and its chaos, confusion and unfairness.

“The army is its own orbit and community and takes care of its own.”

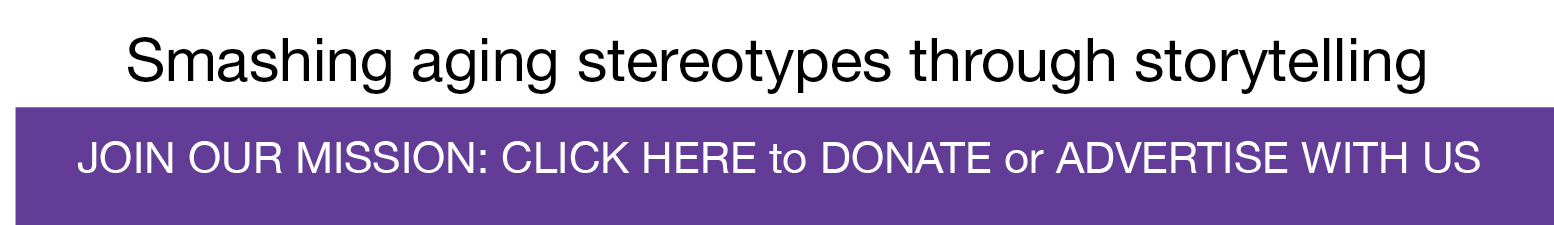

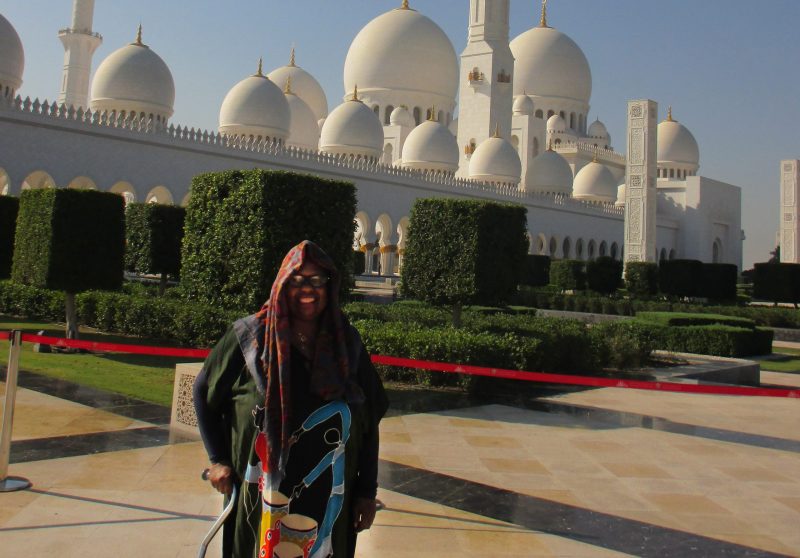

Neither her education nor travel stopped when she retired from the Army in 1994. Within two years, she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. She volunteered, including as a prep cook at Project Open Hand, worked briefly as a teacher, got certificates in coding and graphic and website design and is still taking classes, including at the Fromm Institute for Lifelong Learning in San Francisco. And, she has toured about 25 countries, covering most of Europe, the United Arab Emirates, India and South Africa.

Everything separated by race

Simon was born in 1947, a time when Jim Crow laws ruled throughout the south and as far north as Washington, D.C. “Everything was separated by race,” she said.

When her mom took her to the movies, they sat upstairs. Only whites could sit downstairs. They couldn’t sit at the lunch counter at Woolworth’s. At Georgetown Hospital, where she was born, there were two wards — one for black patients, one for white. Neither had any black nurses.

Her parents, who had grown up on a farm, ended up in Washington D.C. as part of the Great Migration of some six million African Americans who left the south for more opportunities and work. Her father worked construction in the nation’s capital, but when a better paying job as a building supervisor in New York became available, the family of three moved. Her mother would be the bookkeeper for the rental operations.

Worried the transition for Simon would be stark, her mother patiently explained she would be attending with white children and what to expect. Not only had Simon never been around white children, she said, “whites never came into my neighborhood – except policemen, and I was taught to fear them. Police were nicknamed ‘Bulls’.

Integration eases fear of whites

“I was afraid because I thought white children were from another planet; they would eat me. It wasn’t until a little white boy fell in the school yard and scratched his leg; he cried and I said, `Oh, he’s human.’ ”

Slowly, she adjusted and began to thrive. The school had adequate books and supplies, not to mention free breakfast. She made friends, who liked reading. “Carol-Ann and Arlene loaned me their comic books, and I started from there. They took me to the library to borrow books over the summer.” It was her first time in a library. District of Columbia libraries were still segregated when she was there.

“I hated school while living in D.C.,” she said. “It was not just the segregation, but I was not ready to learn.”

That changed at her new school. Simon’s summer reading helped put her in an upper-level reading class and sparked dreams of college. “I began to want to learn how to read and began to like school and my favorite teacher Miss D’Angelo when I was in the third grade.”

After high school, she worked various clerking and secretarial jobs and took college courses in English and French in the evenings. She never married or had children, which made it easier to care for her mother, who was often ill, she said.

In 1970, she moved to San Francisco, worked as a secretary typist at the University of California-San Francisco and the California Medical Association. In the evenings, she took college courses in French, math and economics.

Rising in the ranks

Then in 1976, seven years out of high school, she joined the Army. Her first post was at West Point, the same year the famed academy began enrolling women cadets. “I left in 1980 and watched that class graduate, and I felt that I graduated, too, as the cadets threw their white hats in the air.”

She was assigned to food service at West Point, for which she had an interest but no previous experience. But she learned quickly on the job. “I loved being the night baker and decorating cakes, besides making cookies, pies, biscuits, and puddings for the soldiers daily; my cinnamon rolls were the best!” She also was the only cook who would make lasagna for the West Point band, she said, “because it was too much work.”

With promotions, she eventually became a food service sergeant, overseeing the feeding of as many as 500 people a day. Her duties eventually took her to Germany and the Middle East. “I supervised 12 cooks and trained most of the privates, which I loved doing,” she said. She also cooked for colonels, generals and others who frequently did not show up, she said

Cooking in a war zone

She cooked in the desert and the wilderness of Germany’s outdoors. She and others set-up and broke camp with portable kitchen trailers in war zones. In Kuwait during the Gulf War, she said, fresh food was served morning and evening. The only difference from non-combat meals was the dried lunch, which “no one ate.” She was never injured but remembers driving through the Iraqi desert at night with bombs being dropped into Iraq. “We later saw many burned-out cars, but no bodies.”

While the Army kept her plenty busy, her appetite for learning never waned. On weekends during a three-year post at a missile launch pad in upstate New York, she drove to Cornell University in Ithaca for classes in Le Cordon Blue cooking and hotel and restaurant management. She also studied theology, English and nutrition.

While in Germany, she learned the language and earned an associate degree in liberal arts from the University of Maryland’s European Division.

She never stopped learning

Two years after leaving the Army, she earned a bachelor’s degree in Human Resources from Golden Gate University. Then, she tucked into post-graduate studies, completing a master’s in education in 2000 at Stanford University and later a master’s in human resources from Golden Gate.

She tried teaching in the San Francisco public schools – because of Miss D’Angelo, her third-grade teacher, she said, “I felt that teaching and helping people was meant for me. Teachers knew so much.” But she found the work didn’t suit her and turned her energy toward volunteering and learning, more learning.

She kept her eye out for interesting jobs but didn’t really have to work. The Army had been good to Simon.

It provided her a comfortable retirement. It recognized her talents. She won awards for her cooking and received a Bronze Star and the Kuwait Liberation Medal for her service during the Gulf War campaign. “Truth be told, it was more challenging being a woman than being black,” she said.

While serving, and even after retiring, Simon took every opportunity to see even more of the world – and keep on learning.

As she reaches a milestone of 74 years, she finds comfort in continuing education classes on Zoom, taking in the politics of the day via radio and television at her Park Merced home and planning a trip to another continent.