People over age 51 remain a steady, sizable portion of people living on the streets and in the shelters of San Francisco

Next time you see a homeless person on a San Francisco street, look again. There’s a good chance that person will be a senior.

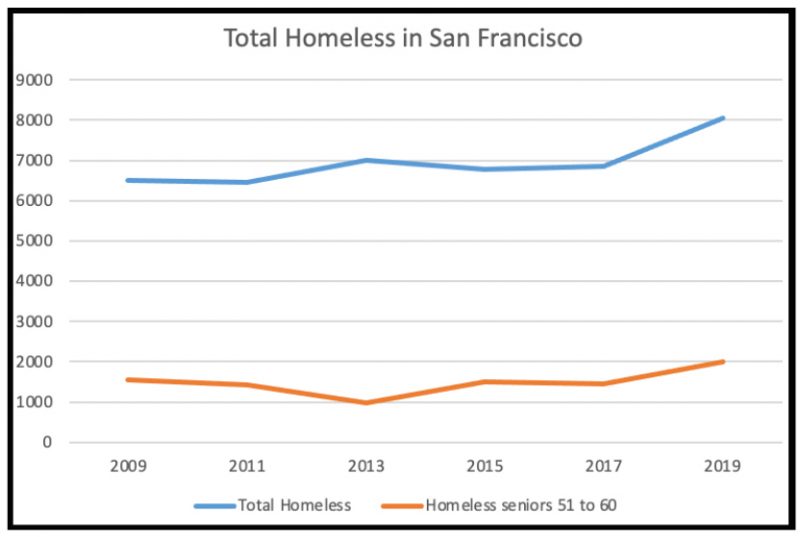

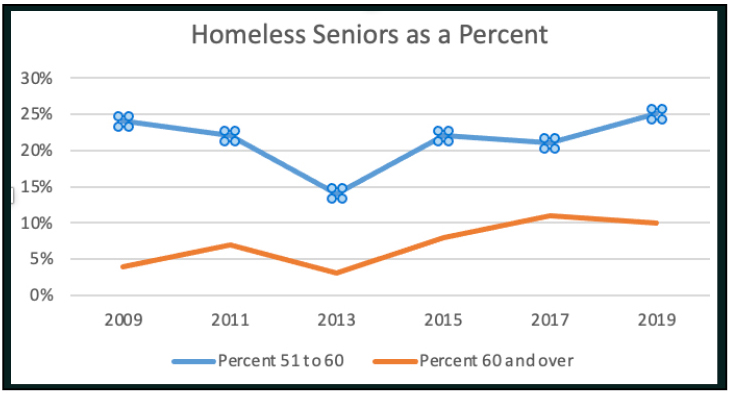

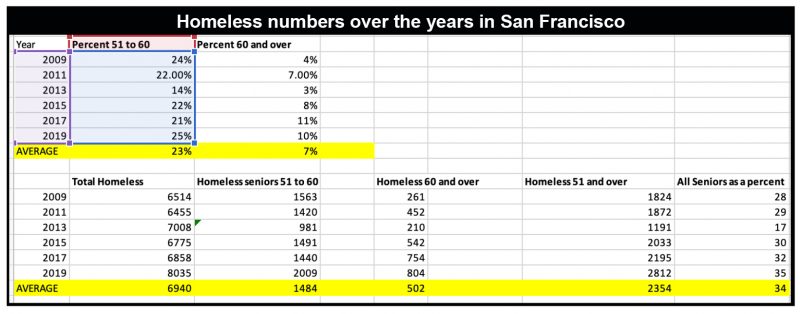

Since 2009, people over the age of 51 have consistently comprised nearly one-third of the people living on the streets or in shelters in San Francisco. In 2019, the last time the city conducted its biennial “Point in Time” count of the homeless, there were 8,035 unhoused people, including 2,009 between the ages of 51 and 60, and 804 over the age of 60.

Distressing as those numbers may be, there’s a consensus among people who follow the homeless issue that the count likely overlooks significant numbers of the unhoused, including the elderly. “It’s hard to believe they can find everyone in just one night. People might be off the street for a day, crashing at someone’s house and they’re missed,” said Deanna Crespo, crisis manager at St. Dominic’s Catholic Church, which offers a variety of services for the homeless in San Francisco.

The good news

While the pandemic has had tragic results for much of the population, there has been one positive development for the elderly homeless: San Francisco’s emergency shelter-in-place program, or SIP, has found temporary housing at various times for 3,600 people over the age of 65 and individuals with health conditions that make them especially vulnerable to Covid-19, according to the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

“I think the SIP program has gotten many – though not all – of the elderly homeless off the street,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness, a San Francisco nonprofit.

Initiated last year, the shelter-in-place program housed people in 29 hotels and motels leased by the city and offered at least a modicum of services and meals. The program is expensive; it costs $260 a night per person, with the Federal Emergency Management Administration ultimately picking up the tab, according to Deborah Bouck, a spokeswoman for the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

But for 65-year-old Susan Griffin, it was a life saver. Family problems and other issues led to the loss of her savings and her apartment. “I was in a downward spiral and got evicted. All I could do was couch surf,” she said. The next stop might have been a shelter or the street, but Griffin qualified for an SIP room at the Chancellor Hotel on Powell Street.

Unlike the typical single-room occupancy hotel, rooms at the Chancellor have private bathrooms, televisions, and the staff delivered three meals a day. “It was very loud, they did three bed checks a day, and many of the people had substance abuse issues. But I’m not complaining. I don’t know how I would have existed without it.”

The SIP program is ending in September and is already being phased out. But with $800 million raised via Measure C, the city plans to buy or lease hotels and motels next year and convert them to supportive housing. Meanwhile, the city has pledged to find housing for residents of the SIP hotels when the program ends.

Lost jobs, evictions top causes

It’s not yet clear if housing homeless seniors in the new facilities will be a priority, and documents about the planned acquisitions on the Homelessness Department’s website make no mention of older adults, saying: “Permanent Supportive Housing is affordable housing designed for adults, youth, and families with chronic illnesses, disabilities, mental health issues, and/or substance use disorders who have experienced long-term or repeated homelessness.”

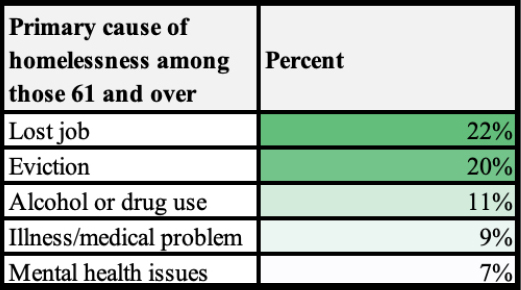

It’s no surprise that the Bay Area’s critical shortage of housing and skyrocketing rents are being blamed, in large part, for the epidemic of senior homelessness. When unhoused adults 61 and older were surveyed during the 2019 PIT count and asked why they had become homeless, 22 percent said it resulted from a job loss and 20 percent cited an eviction.

“The fastest-growing segment (of the homeless) is 51 and older who are homeless for the first time,” said Sharon Cornu, executive director of the St. Mary’s Center in Oakland, which serves and delivers thousands of meals a year and offers a myriad of services for the homeless.

“We are seeing that seniors who have been housed their entire life, worked in a variety of occupations become unhoused through no fault of their own,” Cornu said. Losing a job at an age where finding a new one can be extremely difficult is high on the list of factors that push older people onto the street.

That’s what happened to Cynthia Yates. The 70-year-old Atlanta native had a steady job as a home health care aide, which came with a room in her client’s home. But when the client died and the home was sold, Yates had no place to live. She stayed with friends for a while, but soon was running out of options and was facing knee surgery.

A social worker at St. Dominic’s paid for and made a reservation for Yates at a hotel room for a few nights. But when she got to the hotel, Yates found that the only way to enter was by downloading an app. Like many seniors, Yates is not comfortable with technology and couldn’t figure out how to gain admittance with her phone. In tears, she waited on the street until a kind passerby noted her distress and used her smartphone to help Yates enter the building.

A microcosm of the nation

San Francisco’s senior homelessness crisis mirrors that of much of the United States. Nationally, there were an estimated 40,000 people age 65 and older who were homeless in 2017, according to a study by researchers in Los Angeles, New York and Boston. That number is likely to nearly triple to 106,000 by 2030, they said.

The human and financial costs of senior homelessness are profound. Like Yates, older homeless adults have medical ages that far exceed their biological ages and they experience geriatric conditions, such as loss of mental acuity and mobility, at rates similar to people 20 years older, the researchers said.

“Caring for this elderly group in homelessness is going to cost about $5 billion a year – that’s just for their health care and shelter, not to house them,” said Dennis Culhane, the principal investigator of the study.

San Francisco has struggled to end homelessness for years with little success and little public recognition of the toll homelessness exacts on seniors. But the city’s willingness to finally develop a large network of supportive housing could make a difference.

Friedenbach is guardedly optimistic that the Measure C money and aid from the Biden administration “might finally move the dial on homelessness. But there needs to be a laser-focus and political will to make it happen,” she said.

Michelle Minolli

I wrote to Norman Lee when he was supervisor and have the emails to prove it. They responded to me with the typical bureaucracy-speak. I had also called called Phil Ting’s office to no avail. Why SCRIE Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption is not instituted here in SF is beyond me. This is done in New York City but we can’t do it in San Francisco? Basically as a senior if your income is $50,000 a year or less you are entitled to a rent increase exemption. In lieu of the increase your landlord would receive a tax credit. I worry about homelessness. My rent increases every year and my income is fixed. I am a candidate for homelessness unless SCRIE is implemented. I even emailed the mayor’s office. Worrying for Seniors impacts longevity. Why isn’t this even brought up? No one can solve the homeless issue. So start here. It’s unbelievable!