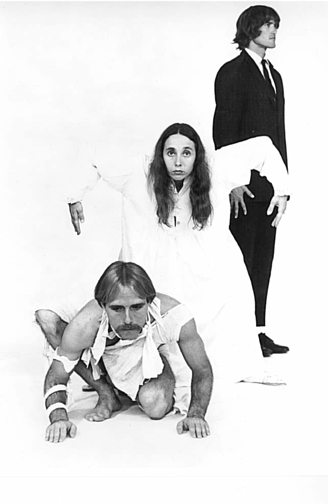

Professional dancer adds props and humor to her repertoire and senior caregiving to her career accomplishments

Helen Dannenberg came onstage wearing a beige jumpsuit then danced a duet with a large, old-fashioned, collapsible ironing board.

It was part of her first 90-minute solo performance, staged at the San Francisco Repertory Theater. It was 1983 and Dannenberg – modern dancer, choreographer and skit writer – was 41. “Old and New, Borrowed and Blue” was crafted from the daily life of her Jewish parents in the 1940s. The muslin-covered ironing board was reminiscent of the pressing machine used by her tailor father.

It got a glowing review from The San Francisco Examiner, which applauded her use of personal experience in developing the vignettes, highlighting them with “outrageous costumes and a motley collection of props.”

It was the first of many such reviews over her 33-year career as a dancer and choreographer. Dannenberg saved them all. She also was awarded four choreography fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts and a California Arts Council artist-in-residence grant. Along with other dancers, she founded a booking agency for independent dancers, in 1982.

But as she approached 50, the pace and part-time nature of the work began to wear. “I needed the security of a full-time job,” she said. She found one as an activity director and then a social services director in skilled nursing settings. She enjoyed working with seniors, she said, but looked at it as temporary till she could go back to dancing. “That’s how I accepted the change,” she said.

But her career in senior care spanned 24 years. “As I realized that I was good in my jobs in skilled nursing and making a contribution, I felt fulfilled,” said Dannenberg, now 78.

Since retiring from senior care in 2018, Dannenberg spends her time producing mixed media art, writing poetry and autobiography, and performing with Cosmic Elders, an improv group.

Dannenberg was part of a modern dance movement that developed in the U.S. and Europe in the late 19th century, receiving widespread acclaim in the 20th. Its focus was intention and acting, not just technical routines. Names like Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham, and Katherine Dunham defined and redefined the genre. Merce Cunningham was a prime influence on its development from the ‘60s onward.

Dannenberg’ contribution was the addition of her New York humor. When asked by the Examiner reviewer why she chose an ironing board as a prop, she said, “I was recovering from a serious back injury and thought I might have to lie down.” In its review of Dannenberg’s “My Reindeer Flies Sideways,” The New York Times said: “It was a wisecracking view of the search, as a mature woman, for male companionship and the absurdity of the rituals involved.”

‘That rare thing in dance’

“Dannenberg is that rare thing in dance: a comedian who is genuinely funny,” it said.

Her use of props and costumes in her dances expanded with her imagination. The first time she created a piece for a dance company, in 1988, she used a puppet, oversized toothbrushes and brooms for a daffy juggling act – a take-off on the “Matchmaking” number from “Fiddler on the Roof” – and store-bought noses.

Facial expressions were another way she made humorous statements. “I watched Imogene Coca on Sid Caesar’s ‘Show of Shows’ growing up and was entranced by the way she moved her face,” Dannenberg said. She also studied how Caesar manipulated his face and body.

Dannenberg began choreography after injuring her back in 1975. “I was the only one who knew what my body could do,” she said, adding that all of the other modern dancers were entering chorography. To design choreography for others, Dannenberg asked her dancers what their interests were and weren’t, noted their skills, and then “put odd bits of things together.”

Dannenberg grew up in Brooklyn, the daughter of Polish immigrants. Trained as a tailor when he was just 11, her father supported the family by operating a tailoring and dry-cleaning store.

Before she entered grade school, Dannenberg danced when her mother turned on the classical music station, WQXR. “Our parents wanted my sister and I to have advantages, so I started dance lessons in first grade and my sister played the piano,” she said.

Dannenberg’s private dance studio teacher would show her students movements and then ask them to improvise. “She said, ‘Variation, Variation.’ I didn’t know what that meant so I tried this and that,” Dannenberg said. “This may have primed me for future creativity.”

The early days

After graduating from the High School of Performing Arts in 1959, she set her sights on becoming a professional dancer. “I tried college, but it wasn’t interesting,” she said. She supported herself with office jobs while dancing in several companies, including the Merry-Go-Rounders and the Fred Berk Dance Company, which did folk dances and performed in schools. “It was much easier in the ‘60s to become an artist; one didn’t need much money to live,” she said.

Dannenberg married a fellow performer in 1962 who suggested they move to the West Coast. “I was hesitant because I didn’t think anything culturally worthwhile existed outside of New York City,” she said.

The couple moved to San Francisco in 1970 and she settled in. She danced in different troupes and invited dancers to perform with her, happy to put people together. But “since it costs so much for the performance space and publicity, there was nothing left over to pay them,” Dannenberg said.

A long-awaited compliment

Dance alone didn’t provide enough financial support for Dannenberg either. So, she concentrated on teaching modern dance, including at the Margaret Jenkins dance studio in San Francisco and several colleges and universities. That along with grants and financial awards helped for many years.

But in 1992, admitting she needed regular work, she went to the Employment Development Department for help. Liking the work she found at a skilled nursing facility in San Francisco, she completed a certification course and stayed in senior care for more than two decades.

She danced occasionally while working in senior care, including a stint with June Watanabe at Theater Artaud. She also, with the aid of a grant from the California Arts Council, designed an innovative program for seniors at Menorah Park, a senior housing complex in San Francisco. Participants generated autobiographies through writing, poetry, narrative, the spoken word, movement and music. One participant, Gerda Keating, told a reviewer she became a “kosher ham” after performing her theatrical piece, “Miracle of My Knees,” about her recovery from two surgeries.

Dannenberg never abandoned her love of dance, despite the financial vagaries and her father discouraging it as a career. “It was only for rich people,” he told her. But when he saw her perform in New York City, he admitted she really could dance.

She was overjoyed with his compliment but also conceded, “he was right about dance being a hard way to make a living.”