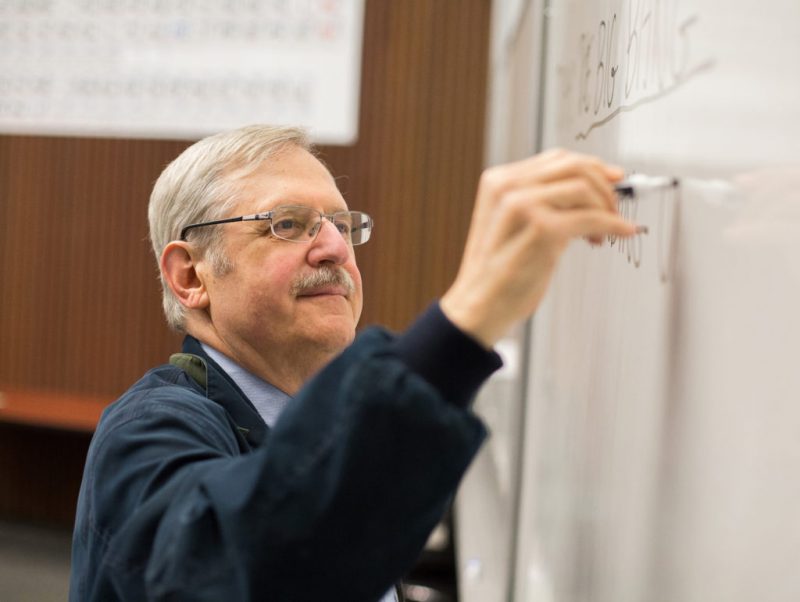

Teaching children, students and adults about planets, black holes and asteroids is this astronomer’s true calling

Famous people and even not-so-famous people in San Francisco have streets named after them. But Andrew Fraknoi, a well-known science educator and astronomer, goes those long-dead presidents, generals, and madams one better: He’s the only person in the city to have an asteroid named after him.

The International Astronomical Union dubbed a hunk of space rock “Asteroid Fraknoi” to honor his work educating the public and spreading enthusiasm for astronomy over a career that has spanned more than four decades. He’s proud of the honor, of course, and has a photo of it on his wall, though the former Asteroid 4859 only appears as a streak of light in the heavens.

Fraknoi, 73, is quick to point out that his namesake asteroid is nothing to worry about. “It orbits peacefully in the main belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, and is not a danger to planet Earth,” he said.

You may have heard Fraknoi on local and national radio, where he’s been a go-to guy for journalists needing an informed but understandable comment on matters astronomical. He retired in 2017 as the chair of the astronomy department at Foothill College and now teaches introductory astronomy and physics for older adults at the Fromm Institute of the University of San Francisco and through the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at San Francisco State University.

He sprinkles his talks and lectures with what he admits are “dad jokes” and comes across like your favorite uncle. But he also has a collection of slides, charts and photos he uses to explain complex matters, from Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity to the creation of the colossal black hole at the center of our galaxy. And befitting a male professor in the “me-too” era, he pays tribute to female astronomers like Jocelyn Bell, whose contributions were minimized or shunted aside in favor of the work of male colleagues.

It all started with the Man of Steel

Comic books and science fiction novels, said Fraknoi, sparked his interest in astronomy.

A native of Budapest, he and his family fled during the failed Hungarian uprising of 1956. After a brief stay in Austria, they settled in New York, sponsored by his mother’s sister. Fraknoi was 8 at the time.

“I didn’t speak a word of English.” he recalled. But his mother, a translator, was fluent, “and she thought that one of the best ways for me to learn English was to read comic books because they’ve got pictures that help you figure out what the words are.”

Soon, he was thrilling to the exploits of the Man of Steel. As his English improved, he started reading science fiction. “And that led to a lifelong fascination with outer space and with spaceships and other planets and things like that.”

A visit to New York’s Hayden Planetarium (now part of the Rose Space Center) was so much fun he hid from his parents so he wouldn’t have to go home. “I began to realize that you could do space and spaceships and planets for a living. And it struck me as an incredibly exciting prospect that it wasn’t just fiction,” Fraknoi said.

After completing his undergraduate studies at Harvard, Fraknoi moved to the Bay Area to attend the University of California-Berkeley, where he earned a doctorate in Astronomy. “I did some research in graduate school and began to realize that education and popularization was my specialty.”

Wanting to do a good job as a teaching assistant, “I snuck in a course on teaching, and the (faculty) wasn’t happy about that. You’re supposed to be doing research,’” they scolded.

Asked if he thinks of himself as scientist or teacher, Fraknoi replied: “I would say I’m an astronomer by training, but an educator by profession.”

Fraknoi has taught astronomy and physics at San Francisco State University, the City College of San Francisco and Canada College, as well as Foothill. Along the way, he served for 14 years as the executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, an international scientific and educational organization founded in 1889. He’s written several children’s books, teachers’ guides and is a co-author of a free, college-level astronomy textbook.

A love of teaching

He still loves science fiction and has taken to writing short stories that combine real science with science fiction. So far, four of his pieces have been published. One is included in the “Science Fiction by Scientists” anthology.

As for retirement, he said “my wife is always joking that when I said I would retire from Foothill College, everybody expected that I would actually retire from something.” He did retire from something — full-time teaching. But switching to adult education is liberating, he said. “I used to teach 300 students a quarter and have to give 300 grades. It was incredibly wearying.”

He plans to write more science fiction and more children’s books, and continue running workshops aimed at improving the teaching of astronomy.

“I’m not ready to drop those plans yet and I always tell my friends who are about to retire, it’s really good to have a plan for something you want to do that you haven’t been able to do. You need something that keeps you going on mornings when you’re not sure you need to get up.”

Here’s some of what Fraknoi had to say about current issues in space exploration and astronomy during an interview with Senior Beat:

I know you’re on the board of SETI, the search for extra-terrestrial life. Do you think at some point we are likely to find intelligent life on other planets?

I’m more optimistic today about the possibility of ‘seniorbeats’ on other worlds than I have ever been in my career. Because everywhere we look, there are planets. Of course, not all planets will have conditions for life. Not all life will become intelligent. But hey, there are billions of planets out there. So what are the chances that we humans are the only example of intelligent life? I think that that would be an incredible waste of a universe, so I’m optimistic.

As you know, the U.S., China, Russia and others have sent devices to orbit Mars and, in some cases, land. What are the most important things we’re learning about the fourth planet?

We’re not seeing Martians today, but we’re dreaming of Martians long ago. The biggest discovery is that Mars today is as dry as dust. But Mars long ago was not. Billions of years ago it had a much thicker atmosphere. It was able to have liquids on its surface. It had lakes, rivers, even a small ocean. And in that wet and warmer environment, it’s possible that life started and then it ran into trouble when Mars lost its atmosphere and was no longer able to have liquid water on the surface. So whatever life might have started there, probably died out as the environment on Mars changed.

NASA has plans to send humans back to the moon this decade after a lapse of 39 years. What do you think about that mission?

I don’t see much reason to send people to the moon anymore. People are very expensive and very fragile. And it costs a heck of a lot more to send a person to the moon than a robot. So the motivations are not scientific, they’re political.

How will our sun die and what does that bode for the fate of the earth?

It won’t happen for at least another five or six billion years. When the sun runs out of fuel it will undergo a series of changes deep inside and ultimately it will collapse under its own weight and become a cinder, which we call a white dwarf. We expect it to be only about twice the size of the earth. [Today the sun is about 109 times wider than the earth.] But before that happens, in one of the last stages of its life, it will expand far beyond the orbit of earth, and the earth will be burned to a crisp.

When I was growing up, I was taught that our solar system had nine planets. But Pluto has been demoted, so now there are eight. Is it likely that we’ll find a planet or planetoids beyond the orbit of Pluto?

Well, we already have. There’s another Pluto out there called Eris, which almost no one has heard of. And there are smaller versions of Pluto out there, beyond Pluto as well. Pluto didn’t really get demoted. It got its own category that was given a bad name: dwarf. Which sounds insulting. But there is now a group of astronomers who also think there might be a real planet beyond Pluto; a much bigger planet that we haven’t found yet. They think they’re seeing hints of it in terms of the organization of the outer solar system, how things are moving.

The notion that the universe is expanding is generally accepted. We now know that it continues to expand. Common sense tells you that it should be slowing down. But it isn’t. That seems very strange, doesn’t it?

We knew from discoveries made in the early 1920s that the universe was expanding — that the galaxies, islands of stars, are moving away from each other. And we think that the cause of that was the Big Bang explosion that was the creation event. So you expect that if there are galaxies still moving away from an explosion, as time goes on, they would slow down because gravity is pulling everything. We didn’t have a perfect [method to measure the speed of the expansion] through the 1990s. When we applied a better measuring stick, we found that to our incredible surprise, the motion of the [stars and gases] was not slowing down with time but speeding up. And that’s ridiculous. No self-respecting universe should work like this. Why wouldn’t gravity be slowing things down over time?

If the galaxies are moving faster now, there has to be an accelerator. There has to be some force that does this. And no one knows at this point what that force is, how it got into the universe or when it got into the universe.

Sharon Cox

I have great respect for your ability to make accessible those hard-to-understand aspects of astronomy. That is a skill that takes more than scientific rigor. Thank goodness for your passion that continues to impact students of all ages.

Margaret Baran

You are such a fabulous Professor! Thanks you. I love your courses!! Teach more - maybe another on Quantum Mechanics.

Andrew Fraknoi

Thanks for this very kind summary of my life and retirement. I appreciate all the research that went into it. I might just mention that for people who want to read my science fiction or explore my other writings or videos, they can find them at my website: http://www.fraknoi.com