Glen Park book store owner finds Literature and Live Jazz the perfect match for neighborhood communing, musicians staying employed

Twenty-four years ago, Eric Whittington decided that a career as a word processor wasn’t how he wanted to spend the rest of his working life. Then 42, Whittington and his wife maxed out their credit cards and purchased a small, not-very-successful women’s bookstore in San Francisco’s Glen Park neighborhood. They renamed it Bird & Beckett Books and Records.

It was quite a gamble. In the late 1990s, Amazon was becoming a juggernaut that devoured independent bookstores, eBooks were on the horizon, and it appeared that only mega-chains like Borders would survive.

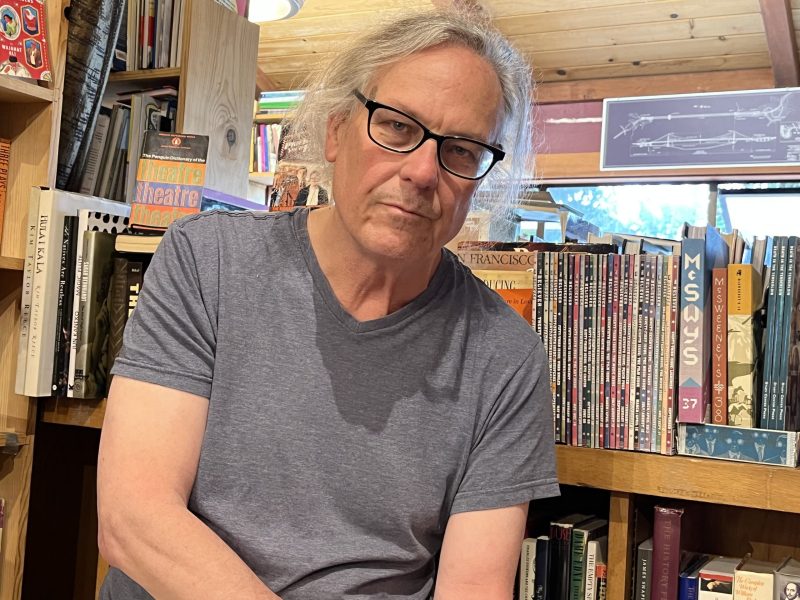

Bird & Beckett did survive. Now 66, Whittington presides over a business that Chronicle columnist Carl Nolte called “the spiritual heart of Glen Park.” It was an apt observation. “People think of this as their little club and I do nothing to disabuse them of that notion,” Whittington said. In fact, he does the opposite. Whittington, an energetic, casually dressed man with long, graying hair tied back in a ponytail, is a welcoming presence, ready to chat about jazz and literature. Indeed, the name of the store says it all. “Bird” refers to jazz great Charlie “Bird” Parker and “Beckett” to literary icon Samuel Beckett.

His store is about 1.500-square-feet and crammed with books and records from floor to ceiling. But it’s best known as the venue where jazz musicians perform three or four nights every week.

Whittington’s efforts are repaid by a corps of loyal neighborhood customers. Glen Park resident Barry Biderman has been buying books and listening to music at Bird & Beckett for more than 20 years. One day recently, he was browsing at a well-known bookstore in another part of town. He saw a few titles he liked, but rather than buy them, he noted their names and ordered them from Whittington. “Bird & Beckett has kept jazz alive. You’ve got to support them,” Biderman said.

From customer to performer

Whittington learned to love jazz while living in Japan, where his father was stationed with the Navy. “I got to hear greats like Thelonious Monk and Count Basie when they toured there. I guess it blossomed,” he said. A few of his early customers were musicians, and Whittington asked them to perform on the store’s tiny stage. Other musicians later approached him and said if the store had a stable series they would be willing to play.

The Friday night gigs were a hit, and soon they were weekly events. Since the early 2000s, “we only missed two Fridays. One was Christmas and I can’t remember the other,” he said. The store now hosts about 200 performances a year, including poetry readings and literary lectures.

San Francisco’s once-vibrant jazz scene is much reduced, but Bird & Beckett has filled at least part of the breach, becoming an important venue for Northern California musicians and the occasional visiting artist from New York and other distant cities. One reason: better pay.

Even skilled jazz musicians struggle to make a living. Often they are at the mercy of whatever donations patrons will drop in a tip jar. Whittington, who makes no bones about his pro-labor stance, has always paid his musicians: “I was embarrassed to ask them to work for free,” he said. Initially, Whittington paid musicians out of the cash register and, yes, a tip jar.

A job at Green Apple

He became a co-founder of the Independent Musicians Alliance and works closely with Jazz in the Neighborhood, a group aimed at improving the working conditions of jazz musicians and establishing minimum rates of pay. It sometimes helps venues pay musicians. Whittington, though, relies on cover charges and funds raised by his nonprofit Bird & Beckett Cultural Legacy Project. “We can’t do it without donations,” Whittington said.

At Bird & Beckett, each member of a performing quartet is paid $150, with a small bonus for the band leader. It’s worth noting, Whittington said, that setting up for a show, playing two sets, and traveling to and from the venue, can amount to hours of work, resulting in an effective take-home pay of just $30 or $40 an hour. “It’s really not enough. But it’s something,” he said.

For musicians, it’s not just about the money. “Eric is incredibly supportive. He gives us the freedom to do want what we want artistically,” said Scott Foster, a jazz guitarist who has been playing at the bookstore since 2002. Foster, chair of performing arts at the Urban School, was in his mid-30s when he began playing at the store. “For me, playing with musicians in their 70s was a huge education and a help to my musical development,” he said.

Whittington was a military kid, born in China Lake, Calif. His family moved frequently as his father, a member of the Navy, was transferred around the U.S. and eventually to Yokohama, Japan. He played drums and the trumpet as a teenager, but was never serious and soon stopped.

He got his first bookstore job in the summer of 1975 after his freshman year at the University California-Berkeley, packing and shipping books for Ed Hunolt’s Berkeley Book. After dropping out of Cal, he moved to San Francisco and worked for Green Apple Books, where he learned the basics of the business. “It set the model for this store,” he said.

Film studies and music promotion

Whittington knocked around a bit, helping a friend’s unsuccessful attempt to launch a used books megastore in Los Angeles, and returning to Cal to study filmmaking. The film studies degree led him to a job as operations manager of the San Francisco International Film Festival for a few seasons. Later, he co-founded a music promotion partnership in San Francisco “that taught me what I know about booking and presenting live music.”

In the late 1990s, his wife, Michele, wanted to help Whittington leave word processing behind and find a new career. When she learned that the women’s bookstore in Glen Park was for sale, she convinced her husband to buy it. “It wasn’t a gamble,” he said. “It was what we needed to do.”

Those early learning experiences were helpful as Bird & Beckett started up, but ultimately, he said, “the bookstore (his own, that is) taught me what to do.” He learned the importance of publishers in the literary food chain and is dismissive of the trend of self-publishing. “You’ll hardly see a self-published book in the store, though he does carry some.

Whittington moved to a larger space in 2008, taking over what had been the Glen Park branch of the San Francisco Public Library. “I’m fortunate to have a landlord who never raises my rent,” he said. The extra space allowed for a much larger selection of new and used books, a bigger stage and more seating for customers.

The music events were rather clubby and skewed older at first. “Old codgers, musicians and their wives would come and bring friends,” Whittington said. One thing Whittington has always insisted on — and musicians appreciate – is silence from the audience. He’s quick to hush people who make noise during performances.

No sunset in sight

The audience is broader now, there’s a cover charge, and the city stopped Whittington from offering wine and beer for sale during performances, making the scene more professional but not quite as warm, Whittington acknowledged. He encourages patrons to “BYOB” and many bring drinks, coffee and snacks.

He stayed open during the pandemic but was cautious. At first, he’d take phone orders and deliver the books personally. Later, he’d allow a few masked customers at a time into the store. Live concerts made way for streamed events. Initially, the events were on Facebook, but the technical quality was spotty. “The technology was beyond what we knew,” he said. But Whittington and his small staff figured it out, and the live stream is now on YouTube as well as Facebook. There’s no cover charge for watching a stream, but Whittington asks viewers of live performances to contribute what they can afford.

Business during the pandemic was, perhaps surprisingly, stronger than average, he said. People couldn’t socialize or attend live events, so they opted to buy books. Live performances came back slowly as the city eased restrictions. At first, he only allowed one or two musicians at a time on the stage and the audience was virtual. Audiences have been back for months, but as the pandemic eased, so did sales. He’s liable to make some adjustments come fall, perhaps earlier starts for performances and a somewhat reduced schedule of events.

Longer-term, Whittington isn’t going anywhere. He lives close to the store, and said “I get bored when there’s no show to put on.” He figures he can run it for another 10 years or more and maybe one of his three grown children will take over. But for now, “there’s no sunset in sight.”