Love of food and baseball frame a life of service to the city of San Francisco

Ricardo Hernandez, a die-hard fan of both the San Francisco Giants and food of all kinds, had no idea that after retirement, he’d have a change of heart.

From his youth in Puerto Rico through moves to other countries and settling in San Francisco – where he held positions as city Rent Board director and Public Administrator and Guardian – he enjoyed a lifetime romp through a variety of international cuisines – visible in the 264 pounds on his 5-foot-7 frame. His doctor told him, ”You’re the healthiest fat man I know,” he recalled with a thin smile.

He was simply doing what his mother told him back in San Juan, where he was born: “No matter where you are, eat what’s put before you.”

At 13, he was shaving and hungry “all the time.” He was chubby as a kid, yet quick on his feet for the daily sandlot baseball games he loved. But he wasn’t much for the long haul.

No problema.

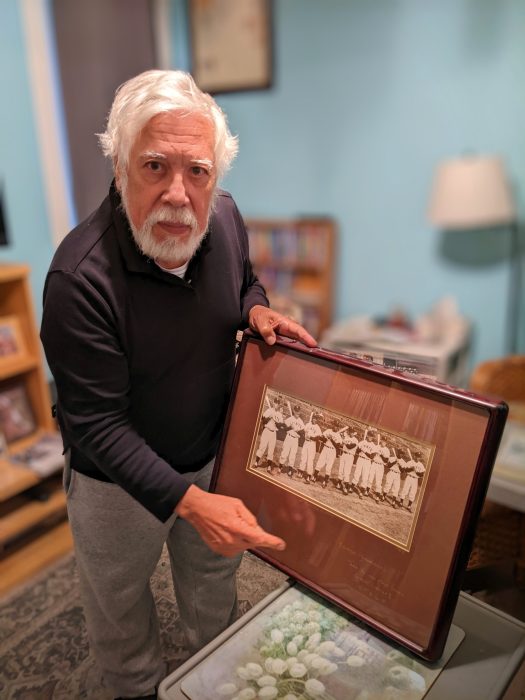

Baseball was the daily vitamin Hernandez consumed along with a rich Puerto Rican diet. It was a regimen he carried on into adulthood. He has collected 670,000 baseball cards, a pastime initiated when his young daughter brought him two autographed ones.

He and his wife, Deanna, have been Giants season ticket holders for 30 years. For several years, he served on the team’s Community Fund, which distributes cash to projects such as youth programs and the AIDS Foundation. He headed its Day Laborers program for a time, and for seven years was on its health committee.

From joy to disaster

On Oct. 1, 2021, Hernandez was watching TV as the Giants played their last regular season game against their dreaded adversary, the Dodgers, in Los Angeles. When they won, he raced into the next room to tell his wife, Deanna.

“Then it felt like a platform of steel fell on me,” he said. Suddenly he was drenched in sweat, feeling lousy, confused and scared. Deanna called 911; the firemen arrived in four minutes. At the hospital, doctors found three blocked arteries and put in three stents.

“I went from joy – the Giants had just won their 107th game – to disaster,” he said. His cardiologist told him, “Take one of these pills once a day or you die. And, absolutely no fat!”

Goodbye hamburgers. Chow cioppino. Adios pork. His wife went out and bought fish and vegetables, the “rabbit food,” Hernandez used to make fun of. Smiling at his change of heart, he acknowledges he eats rabbit food all the time now and admits he has come to love fish.

He dropped 50-plus pounds in just a few months.

Feasting is one of life’s great pleasures and all through life, Hernandez never held back.

“Every wife in Puerto Rico serves rice and beans twice a day, seven days a week, usually with a little pork or chicken,” he said, sitting now in his Noe Valley living room. “And oh, I love pig. We fried everything, too, even the chicken skin.”

A global foodie

Menus got diverse as he moved with his family as “an Army brat” wherever his father, a non-commissioned officer, was transferred.

The succulence of a thick steak, cioppino, pork fried rice, schnitzel and shepherd’s pie were favorites, along with jaunts to McDonalds and Burger King.

His life took many geographic and dietary turns before he settled in San Francisco, a culinary cornucopia of its own.

The family’s first transfer was to an Army base in Arkansas. It was also his first time “‘Colored” and “White” water fountains. He finished fifth grade there, sixth grade in the Bronx when his father was sent to Southeast Asia, and was back in Puerto Rico for the eighth and ninth grades.

“There are two kinds of drinks in Puerto Rico”, Hernandez said.

“Rum and Coca Cola.” At a young age, he combined them.

He had good grades, but school got more attractive when the family was transferred to Frankfort, Germany. “It was an American school and had kids from all over the world.”

He had a favorite professor who made the study of governments intriguing: Students were required to read the Stars and Stripes newspaper every day for pop quizzes.

He joined the football team. “In the old, single-wing formation, I played tackle – I was always a little chunky,” he smiled. Over weekends, the team competed in Berlin and London, among other venues.

Back in the states, after graduating, he went to college first in Oklahoma, then after another transfer, Texas Western College in El Paso. He got a degree in political science in 1969.

Army veteran

He had ROTC under his belt, too. He was a chest beater who wanted to go to Vietnam and fight in the war. He enlisted in the Army and was sent to Ft. Polk in Louisiana, where he again noted the “Colored” and “White” drinking fountains.

Because of his ROTC experience and high test scores, he got special, albeit dubious, consideration. “They made me a platoon leader and gave me 20 Blacks and 20 Mexicans,” he said. “A judge had given the Blacks a choice of prison or the Army. The Mexicans had joined to become U.S. citizens.” Half of them didn’t make it back from Vietnam.

Next, he was sent to radar technician school, then to a long assignment in the German Alps to monitor Russian activities. For a tough Puerto Rican kid from the subtropics, the Cold War didn’t suit him. “And I hate snow and cold weather.”

After being discharged and saying goodbye to mess halls, heavy German cuisine and first-rate beer, Hernandez looked for a job in government. He accepted an offer from the feds for a three-year internship in Washington, D.C.

He became a budget analyst and reviewer of grants, rotating between the departments of Health, Education and Welfare. The daughter of one of the senior employees became his wife. Their daughter, Magda, was born in 1972.

At some point, interns had to rotate out of the area to work in a federal office of their choosing. Hernandez chose San Francisco. He didn’t know it then, but it was, as he says, “a move of a lifetime.”

Public guardian

He worked as a grant writer in various Mission District nonprofits while “trying to bring all the Hispanics together as a collected political voice.” An activist sympathetic to the changing times, he wore platform heels and paisley shirts and had long hair. “I was sort of a hippie.”

When it was time to rotate again, the family, hopelessly in love with San Francisco’s beauty, diversity and politics, decided to stay.

In 1980, he went to work for the city, under then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein, a city supervisor catapulted to the top job on Nov. 27, 1978, when George Moscone was killed.

For nine years, Hernandez served as director of the city’s newly established Rent Board. His longest stint before retiring in 2001 was 12 years as the city’s Public Guardian and Administrator, under the city’s Department of Public Health.

When people die alone, rich or poor, and have no relatives, a judge appoints the Public Administrator to handle their estate. Unclaimed wealth goes into the department’s budget for salaries, fees, client debts and office expenses. The Public Guardian sets up conservatorships for incapacitated adults or children whose parents can’t take care of them, often because of addiction or mental issues.

“I had a hundred people working for me, including lawyers,” Hernandez said. “It is a quiet job, not commonly known – there are privacy issues – but it was very busy.” The administrative division had about 1,000 cases a year; the Guardian side oversaw about 500 adults 18 and over.

“It was a lot for a small county. The dead were mostly gays and old people. The SROs (Single Room Occupancy hotels) were full of single people,” he said.

Hernandez oversaw many heartbreaking and bizarre cases, but the top of the list might be the merchant marine in his 70s living in a Tenderloin SRO who won a $3 million lottery.

A rebound

“The man had tried to spend money as fast as he could, “ Hernandez said. “Then he died,” with $2 million left. “We spent a year trying to find any relatives. Finally, we found out he had an ex-wife in Chicago. But she had died some years before. She did have a son, though, and we found him.”

As the years passed, Hernandez, responding to requests, had taken on two additional responsibilities: director of Day Labor and head of the county’s Veterans’ Service office. Eventually, it was all too much work and he retired. “Thirty years in public service was enough,” he said.

But he was proud of being a bureaucrat, he added. “In court, I didn’t represent the city or county; I represented the client, living or dead. Sometimes I had to sue the Health Department.”

For example, if an investigation substantiated a person’s claims that he’d received bad care, say at the city’s Laguna Honda Hospital, or some attendant had filched his Social Security check, Hernandez would represent the patient in any suit against the Health Department.

But these days, instead of focusing on others’ well-being, he’s attending to his own. After his heart attack and up until pandemic closures, Hernandez exercised at 24 Hour Fitness. He did so well, his only medication now is aspirin and some dietary restrictions have been lifted.

Now, he walks 30 to 45 minutes every day – “no hills” – and does exercycle workouts at home. Now 78, he said he feels 20 years younger. “Sometimes as seniors, we forget how wonderful life is.”