Jerry Barrish had a knack for rustling: supplies in the Army, bail for ’60s demonstrators, and scrap plastics for his quirky art sculptures

On a glistening Sunday between January’s storms, Jerry Ross Barrish welcomed a throng of visitors to the opening of his sculpture exhibit at the M. Stark Gallery in Half Moon Bay. The lanky, 83-year-old San Francisco native and retired bail bondsman smiled broadly and said to a guest:

“Usually, I know about 40 to 50 percent of people at my openings; this is great, I only know about 10 percent of everybody here.”

Tall, with bright eyes and a shock of white hair, Barrish is wearing a long black coat and hat. His hands are scarred from years of melting and molding plastics and mishaps with a hot glue gun. His pieces are generally built from discarded plastics of varied shapes: cylindrical, round, oblong or square.

His sculptural assemblages are a kaleidoscope of humanity and the animal world. Check his work and you’re liable to see wild-eyed cellists, jazz musicians, demure brides, banjo-playing cowboys and tangoing lovers — not to mention a menagerie of cool cats, penguins, foxes and sly dogs, all made with found materials.

Some are constructed from umbrella handles, takeout containers, car and vacuum cleaner parts, wires, funnels and broken toys. He used to find his materials washed up on the shore, but now the beaches are much cleaner, so he prospects auto dismantling yards and recycling centers.

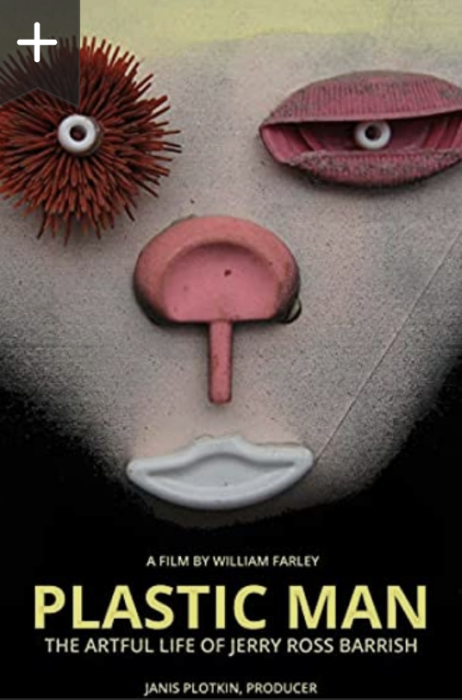

The 2014 documentary film “Plastic Man: The Artful Life of Jerry Ross Barrish” is being shown for free in the auditorium of the Randall Museum, 99 Museum Way, San Francisco, at 2:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25. It can also be seen on Amazon Prime Video.

He now divides his time between a beach house in Pacifica and San Francisco where he was born, raised, and educated, and has long been part of the city’s artistic scene. He has a showroom in the Mission District, which has a small studio upstairs.

Barrish played an important supporting role in the political ferment that swept the city in the 1960s. His bail bond office became the go-to refuge for student protestors arrested in civil rights and anti-war demonstrations. Hundreds were arrested on campuses and on the streets. Barrish bailed them out, trusting that they would appear in court. They almost always did, he said.

Bailing out

He sold his bail bond business in 2013, when he was 73 and coming into his own as an artist.

Paul Karlstrom, west coast director of the Smithsonian’s, Archives of American Art, said “there is a tenderness to his pieces. Who would have imagined anybody could do this with plastics? I think that’s the brilliance of Jerry Barrish.”

For a man who grew up in a family home that was “devoid of art,” his improbable success as a working artist is something he said never imagined. “I am living a life I could never have dreamt up.”

He was raised in the Sunset district, at 28th and Noriega, and “grew up around a lot of tough Jews,” the eldest of three children. His father had been a professional boxer who later worked in sales. His mother worked in retail.

“We were poor. My parents were penny pinchers. I was never taken to a museum or a concert.” Learning was difficult; he was always in the remedial class: “My worst nightmare was being called on to read aloud.”

Years later while watching a “60 Minutes” segment, he discovered his learning issues were classic dyslexia.

By the time he graduated high school in 1957, he’d already started going to galleries, concerts and art openings on his own. He was intrigued by the Beatniks and though too young to get into the bars or clubs like the Co-Existence Bagel Shop in North Beach, he walked the streets and watched the scene.

Feeling like he had few choices, he joined the peacetime Army right after high school and discovered an aptitude for rustling up stuff, a talent that would later shape his artistic development.

He was trained as a truck driver at Fort Ord, but when he was stationed in Germany his superiors depended on his ability to scrounge when they couldn’t get supplies through conventional channels. “I was good at finding stuff.”

Cigarettes and cold cuts

He recounts being sent on maneuvers in the Black Forest. His first morning there, he noticed there was no coffee, so he asked the company commander for permission to find some.

“So, I am roaming around looking for other military units there in the woods, and I come to this German camp and asked if they’d trade cigarettes for coffee, and they even had beer and wurst and salami! So, I filled up my truck like a delicatessen, all in exchange for Marlboros.”

He was a big hit back at his camp, the go-to guy for everything from cold cuts to carburetors. “I didn’t know I had any of those skills, you are a kid, you don’t know what you can do.”

While stationed in Germany, he also visited museums in Heidelberg, Hamburg and Paris. He left the service in 1961 at age 22, with $10,000 in savings and no clear plan.

At a party South of Market, his father introduced him to a bail bondsman. Barrish decided to open his own bail bond office. The timing was right. It was the dawn of ’60’s with people demonstrating en masse and getting arrested.

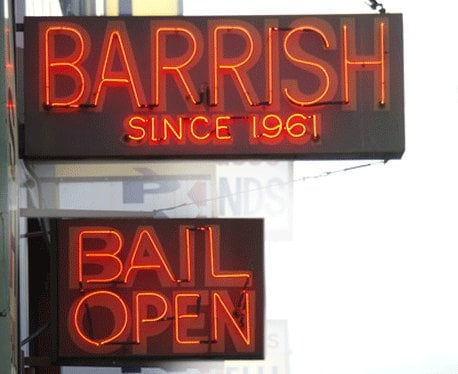

He hung up a shingle right across from the Hall of Justice, above a restaurant called “The Inn Justice.” He worked seven days a week, sometimes sleeping in the office. His company’s cheeky motto: “Don’t perish in jail — call Barrish for bail!”

He got a temporary license, then had to pass an exam within six months. He sweated out those months: tests were a huge ordeal due to his dyslexia. But he passed and made $500 in his first year.

The crazy ’60s

He soon found himself bailing out scores of young activists from the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, the student strike at San Francisco State, sit-ins at People’s Park, and the American Indian Movement’s occupation at Alcatraz.

“First activist I ever bailed out was Terry Francois, Wille Brown’s law partner; he and three others did a sit-in at a Realtor’s office for redlining.” That bail was $50. Then came 58 kids, mostly students, who needed his services. They had been blocking Mel’s Diner to protest the chain’s hiring practices. Demonstrations – and arrests – soon followed at other businesses.

In early 1969, students at San Francisco State College staged a huge demonstration on campus, demanding the establishment of a Black studies department. Lines of police surrounded the demonstrators and arrested hundreds.

When he went to bail them out, “the Black kids said they didn’t want a Jew to bail them out. That shocked the Jewish kids, let me tell you, so we struck a deal: A Black bail bondsman would bail out the Black demonstrators first, and if there was any money left, I would bail out the White kids,” Barrish said.

When he wasn’t dealing with protestors, Barrish got to know a lot of “big shot criminal lawyers” like Tony Serra, who called on him regularly to bail their clients out. “I even bailed out Tony Serra, when he was arrested for tax evasion.”

Around this time, he met San Francisco sculptor C.B. Johnson, asked if he could come and “futz around” in his Bernal Heights studio. There he began to experiment with sculptures made with wax castings and Styrofoam.

Foray into filmmaking

In 1970, he learned that if he didn’t use his GI benefits, he would lose them. So, he whipped up a few pieces for a portfolio and was accepted into the San Francisco Art Institute. The Institute was looking for non-traditional students. “Let me tell you, I thought I won the lottery,” he said.

He was 31 when he enrolled and on his first day there, he was frustrated at the stratification he saw. “The potters were upset with the sculptors, there was a lot of arguing, and I didn’t like the artwork I saw either.“ On a whim, he changed his major to filmmaking. “Maybe I would learn something useful,” he thought.

For the required writing course, he asked the instructor, Dick Fiscus, if he could write a screenplay instead. “I can’t write at all. I still can’t write a postcard or a letter, but I can hear dialogue, I can hear voices and I wrote them down.”

He taught himself to edit using the school’s equipment. The result was his first film, made for $300, based on the Harry Chapin song “The Sniper.”

He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees and while still busy in his bail bond office, made three feature films, including “Dan’s Motel,” which was shown at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1978.

During this busy time, he met his companion, now wife, in 1974 when she rented the geodesic dome he had built out of a kit next to his place in Pacifica. Nancy Mona Russell is an artist in her own right, an abstract painter and, Barrish said, a true partner.

Barrish’s films gained recognition, and in 1986, he received an artist’s grant for filmmaking from the German government. He took a sabbatical from the bail bond company and spent nine months studying and mingling with other artists. He even had a small role in the Wim Wenders’ film, “Wings of Desire.”

But he soon realized that independent filmmakers needed investors, and “no one was asking me to take a meeting.”

A public art landmark

Returning to the Bay Area, he bought an empty lot in the Dogpatch neighborhood and built a small studio where he began creating his signature work. He started collecting discarded plastics and other detritus he found washed up on beaches in Pacifica, where he also had a house.

He wasn’t very mechanical and had to teach himself how to use tools safely. He still has numbness in his fingers from all the times he burned himself. “I started out using a hot glue gun and I burned myself to shit.”

He often creates tableaus, scenes with interacting figures that evoke a whole world: a jazz club, a lonely hearts dance. “For me, my work is about the story, the story that people find in my work.”

In 2013, he was one of nine artists among 300 entrants who received commissions to create a work of public art at the former Naval Shipyard in Bayview Hunters Point. “Bay View Horn” is the biggest piece he ever made, over 15 feet tall, a lean, stylized figure of a horn player towering over the ground.

He made a model out of parts of a plastic rifle he found in the Bayview. The final piece was cast in bronze in a Sacramento foundry.

In 2019, he sold his place in Dogpatch and bought and transformed a janitorial supply warehouse on Bartlett Street in the Mission. It’s a large, light-welcoming space, housing a showroom on the first floor and a studio upstairs.

He’s enjoying the recognition he’s finally earned. Barrish’s work was featured in the 2014 documentary: Plastic Man, the Artful Life of Jerry Ross Barrish. And he’s become a mentor to younger artists. He’s also the artistic director of the Sanchez Art Center in Pacifica, where he works with local artists and curates their shows.

“You know people always say ‘you must have so much fun making your pieces’ and I say, no! — I don’t have any fun; it’s hard work.”

He pauses and looks around at the world he has created in his studio, “It’s when I see it completed, it’s when I finish a piece, then I feel good.”

George Bucquet

Another nice piece from Ms. Marcus. She sure has a knack for bringing to light people's lives. It's a rare gift for someone to bring out another persons story and tell it so well. I look forward to more.

Amy

Who knew that glowing orange neon sign across from the Hall of Justice-- Barrish Bonds-- as iconic to my childhood as the Hamm's Brewery ever-renewing beer glass-- had this whole other layer to it. Excellent piece of writing, Naomi! I loved learning about the man behind the sign and his magical life especially as an artist working in found objects... plastic no less-- Wow! Really an enchanting piece about an enchanting man. Loved the photos as well. Thank you!

Michael Brown

Fabulous portrayal of a fascinating San Francisco character and artist. Thank you Naomi for a lovely reveal.

Dee Harris

A lively, moving and thoughtful profile... brings to life the mind and heart of the artist, along with the community he has worked in and honored over many decades. I feel as if I know him after reading this piece. Thank you, Naomi Marcus, for your insight, humor, and poignant portrayal of this local cultural icon and his work! Fab photos, too, by Colin Campbell. Thank you both.

GM

So well written - terrific insight into the long life and multi-faceted nature of someone that balances work with creation!

Normdeplume

Jerry ran an available, friendly, honest, fair to all bail bond business. He and Debbie made it work for all the customers without delay. His artwork can be seen by looking through the large windows outside the studio on Bartlett. A renaissance guy. From there you can walk around the corner to Purple Star to buy whatever makes you feel good.

Doris Bersing

I have heard about "Jerry" the beachcomber artist who offers salvation to the hopelessly lost trash. However, this piece, so well written is full of nuances and portrays not only the artist's many layers but the man behind a rich existence. The writer really knows how to discover the core of her subjects... and the photographs are another piece of art. Thank you Naomi and Colin.

Judy

Another fascinating profile from naomi marcus! beautiful photos, too! keep up the great work.

Olga Zilberbourg

What a fascinating artist and the piece is so well written! I love knowing about the deals he's made in the Black Forest! So much creativity. Will keep an eye out for his art.