Writer unearths family ancestry in novel exploring Pacific Northwest when fur traders and American settlers collaborated and clashed on Indian lands

You might say Alix Christie’s first historical novel was inspired by her interest in words. “Gutenberg’s Apprentice” charts the creation of the printing press in medieval Germany and the men behind it.

She began her writing career as a journalist. She was a reporter and columnist for the Oakland Tribune and foreign service editor for the San Francisco Chronicle in the late ’80s/early ’90s, as well as a freelance and short-story writer.

Her second novel, just out in bookstores, captures the cultural upheavals in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest through the story of one of her own ancestors. “The Shining Mountains,” begins in 1838 as Angus McDonald, the younger brother of her great, great, great grandfather, arrives from the Scottish Highlands at age 21 to work as a fur trader for The Hudson’s Bay Company.

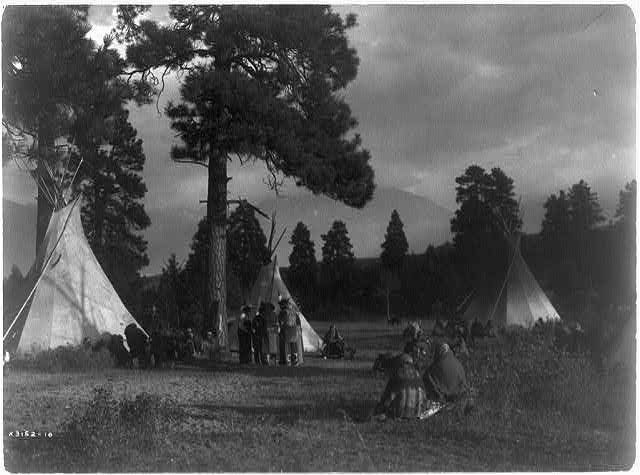

He’s among the many British and French traders building relationships and business with the hundreds of native tribes who have occupied the region for millennia. As American settlers begin arriving, backed by the military in their quest for land, Angus and his wife, a relative of a powerful Nez Perce chief, are caught up in the clash.

What you don’t learn in school

On a rainy day in March as she sat in a Noe Valley dining room, raincoat over a kitchen chair, damp hair pushed back, Christie shared how her family story came to be, her extensive research and her life as a novelist.

When Christie began her research, she said, she had “no idea of the region’s multicultural spread in basically a successful society” of many different tribes and the unions of European fur traders with Indian women. “But that was torn apart by the arrival of the Americans,” she said. “You don’t learn that in school.”

The valleys and plateaus west of the Rocky Mountains, which later became British Columbia and the U.S. states of Washington, Oregon, and parts of Idaho and Montana was then called Oregon Country. Originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain, the United States and Great Britain took joint control for 10 years under the Treaty of 1818, which allowed free trade and opened the lands to claims.

Christie had started researching her family background after her brother wrote a series of articles about Angus’ son, who was born in Montana. She found a trove of descriptive details of Angus’ experiences in his Hudson’s Bay ledgers, stored in the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana.

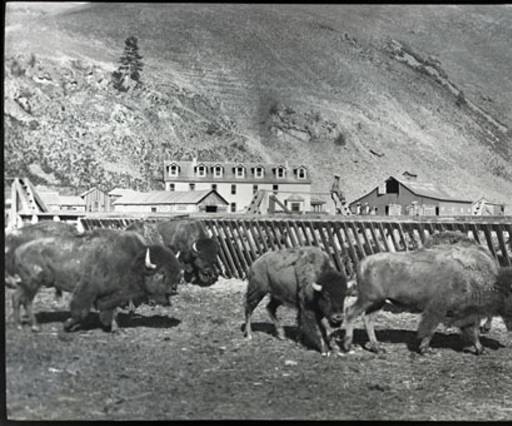

“Angus was highly romantic and highly educated, as many Scots of that time were,” she said. “He wrote copiously in his HBC ledgers” of incidents on the trails, and buffalo and cougar hunts and flowery even romantic poetry, suiting the Victorian age. And at every social opportunity, Angus played bagpipes.

The land is a central figure

The novel winds through two generations to 1877, marked by love, honor, treachery and violence as embattled Indian land continues to shrink.

Christie makes it a point to note that the land is as much a character as her ancestor in this drama. “I just wanted to write the story of my family. But I wanted people to know the history of the area. That’s important to remember.”

Christie, 64, was born in Redwood City but lived in Montana from age five to nine. She learned to ride horses and ski in the vast landscape. She returned to Montana three or four times for the project, driving great distances to interview distant relatives, tribal historians and pore over history books and newspapers of the times.

She was awed by the landscape’s majesty. “It was a beautiful place in the 1960s and still very wild.”

Both of her books took seven years to write and publish, she said. “It’s seven or eight times you write a book. It’s like being a potter; you have to find the shape. And that takes a lot of work.”

And for historical novels, that includes a lot of research. “I start from zero, knowing nothing,” she said, adding that for her latest book, “I photographed history books page by page and newspapers. Extremely arduous. I was taking physical and digital notes all along the way. Being a journalist helped, but this is just bigger.”

Exercise is her way of keeping her mind clear and energy high. She swims up to an hour three mornings a week in the Bay’s frigid 53-degree mix of fresh and saltwater, jumping in at the South End Rowing Club. It’s a routine begun a dozen years ago when she lived in London. Afterward, she writes for two hours.

A little help from friends and fitness

“Few things can bother you after a long swim in saltwater,” she said. On the off days, she does pilates and flexibility exercises. “They keep me in balance.”

She also meets on Zoom every other week with 20 women for online writing sessions. In another Zoom meetup with a small group of artists and writers, her drafts get a monthly checkup. “We talk a lot about process,” she said. “I have always belonged to a group – you need to have people react to your work.”

Christie was without a book contract while working on “The Shining Mountains.” She was supported by her husband, Ludwig Siegele, a German journalist who’s been a staff writer with The Economist for 23 years. “I couldn’t do it without my husband’s salary,” she said. “I have a stable life. You can’t just freelance and make a living.”

They met at a journalism fellowship in Paris in 1991. Christie has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of California-Berkeley as well as one in Fine arts/Fiction Writing from St. Mary’s College in Moraga.

Just one person saying ‘yes’

The couple lived in Berlin for five years when he was the paper’s foreign correspondent. Christie, who is fluent in French and German, wrote articles on Nazi Germany for The Economist and the Washington Post, and on Germany in general for Salon.com. She still writes on culture and reviews books for The Economist.

They were living in London when they moved back to San Francisco in 2019 and now live now in North Beach. They have two children, a daughter working on a master’s in social work and a son who recently graduated from art school.

Christie is currently promoting “The Shining Mountains, including at The San Francisco Public Library, 6th floor, at 6 p.m. May 17.

Peeling back her own history was challenging but not a chore, Christie said. “It’s fun because it’s family – you want to know. It’s a treasure hunt.” And she found open arms in her quest.

“The most rewarding part of researching the book was meeting relatives in Montana and Idaho – all the native descendants,” she said. “It gave me huge insight into the struggles they had gone through.”

Her book acknowledges “the tremendous friendship and support extended to me by my distant cousins on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana. Without the encouragement and advice of tribal and clan leaders, this tale of a Scots Indian family could not have been written.”

In between book signings, she’s keeping her hand in present-day events that will one day be history. Her next stop on a tight schedule this rainy day was a protest downtown against big banks supporting gas and oil exploration. “I answer the call,” she said. “Time to stand up.”

Christie is also working on a memoir. She had had short stories published before, but her first historical novel, “Gutenberg’s Apprentice,” was a career breakthrough.

“I was 55 – my second career– it was a miracle,” she said. “You just need one person saying ‘yes.’ I was tickled.”