Alcatraz docent wants you to know there’s something special to see on the island – and it’s not just the cells of jailbirds

The 1.7 million tourists who visit Alcatraz every year are typically here to traipse through the cell block that held famous jailbird Al Capone. But in summer, there’s something special few are aware of.

“Tourists don’t know this is a bird sanctuary,” said Kimberlie Moutoux, a 61-year-old retired elementary school art teacher and grandmother to seven who’s in her fifth season as a bird docent on this rock island in the bay.

Alcatraz Island, a long mile from San Francisco, is a federally protected bird sanctuary and home to an awesome number of nesting seabirds, 30,000 in fact. July and August are the height of their reproductive season, which began in February.

Moutoux is one of 75 to 80 trained National Park Service volunteers. One to four work four-hour shifts any given day in July and August. They offer a brief education while providing intimate telescopic views of birthing activities in some of the thousands of nests in rookeries around the island.

But Alcatraz is just one of Moutoux’s activities involving birds. A consummate birdwoman, she’s observing, monitoring, and counting birds – “most every day,” she said.

In addition to her Alcatraz shifts, she is a bird counter and tour guide at Filoli Gardens in Woodside, a hawk monitor for the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, a monthly team bird-counting leader on an 850-acre Stanford property, an Audubon trip leader in the Sequoias.

What she loves about birds is their accessibility, she said, adding that birdwatching “doesn’t cost much.”

It starts in the backyard

“We see them everywhere and it can start in your own backyard.” That’s where she began, “watching the little brown birds in my backyard in Pacifica.”

It was the start of Covid shutdowns, and unable to do her normal volunteering – Alcatraz was shut down for a year – Moutoux’s backyard became her focus of interest.

One day an unusual bird showed up, she said. It turned out it was from Texas. “I started investigating; it was a puzzle, a challenge,” she said. “You never know what you’re going to see.”

And there was a whole new vocabulary to learn. “They have interesting lives and habitats to study. As we age, we need to use our minds more and this is a good way.”

Moutoux, about 5-foot-5 and wearing her government-issued brown jacket and hat, is ready at 8 a.m. to board the employee-volunteer Alcatraz Cruiser ferry at Pier 33. It’s a typically foggy and wind-whipped day – the temperature won’t veer far from 59 degrees.

As the boat sways toward the island, she dons binoculars and starts identifying every bird and flock she sees, quickly entering the data in her phone, a count of maybe 30 or 40, four or five species, high- and low-flyers. The day’s data will be sent to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, a prominent institution for increasing knowledge of birds and their habitats.

Moutoux is always counting birds – and intends to even on her planned European vacation. She began studying them seriously after 2017 when her father died.

He was an Eagle Scout in high school and every one of his badges related in some way to birds, she said. An avid birder and Silicon Valley engineer, he took his kids hiking on weekends, using his binoculars to find and identify birds.

A legacy from her father

It didn’t remotely interest her at the time, she said. ”I was too hyper.” But years later, as he lay dying in the hospital, she went every day with a bird she had seen for him to identify. “I did that until he died,” she said.

She inherited her father’s bird books and his record book of all the species he had identified: 273, which included birds on his trips to New Zealand and the Galapagos Islands.

She also got his binoculars, which she’s used since she began volunteering at Alcatraz in 2019.

This month, September, the seabirds at Alcatraz will be gone. Only the land birds – numbering around 350 – will remain. Among them is the yellow house finch. “It turns orange or red, depending on what it eats. I find that fascinating,” Moutoux said. “Available food sources determine the island’s population, and there isn’t much.”

As seabirds depart, so will Moutoux, shifting her focus to other birding activities, including teaching a seven-week course on backyard bird observing. And, she’ll start work on a quilt featuring 19 different bird species.

She began counting birds in her own backyard during the Covid lockdown and has yet to break a string of more than 1,205 consecutive days, with no end in sight.

“I try to do something with birds every day,” she said.

Moutoux, whose “hyper” side keeps her in motion even among the stillness of the outdoors, said bird watching “calms her.” She rarely skips a day of counting. As of late September, she had yet to break a string of more than 1,200 consecutive days, with no end in sight.

As the boat pulls up to Alcatraz, she motions toward the end of the dock. “Look over there,” she said, “It’s pigeon guillemots nesting under there. Good protection.”

These dramatic-looking seabirds – black bodies with a white patch on the wings and stunning bright red legs, feet, and mouths – love to lay their eggs in old drainage pipes and crevices in concrete rubble.

A place to rest and nest

Alcatraz, in fact, got its name from Spanish explorers in the 1770s who found a great population of pelicans, or seabirds (“Alcatraces”). But they were driven away by increased human activity around. They didn’t begin to return until after the federal prison closed in 1963. Vegetation increased and seabirds – who seek islands for nesting – returned by the thousands. But no pelicans.

The island’s map shows the nesting habitats of seven seabird species. The pigeon guillemots are waders and occupy the periphery’s water. Another wading is the snowy egret, once nearly extinct. The slaughter of millions of waterbirds for their elegant plumes to adorn ladies’ hats fueled the creation of the first state Audubon Society in 1896.

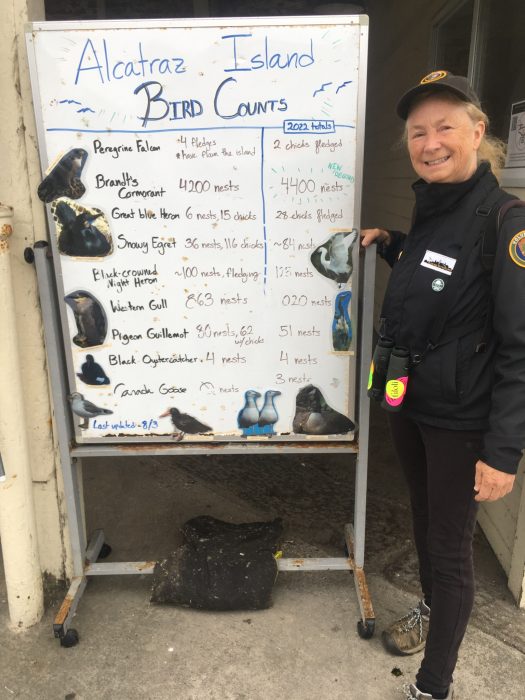

Moutoux pauses at the island’s bird scoreboard comparing last year’s census for nine species with this year’s. The most by far are the Brandt’s cormorants with 4,200 nests. She herself has spotted 509 separate species in the course of her birding.

Seabirds spend their lives on the sea but return every February to Alcatraz. “In breeding plumage, Brandt’s cormorant males have brilliant blue throat patches, which they show off by pointing their beaks skyward, according to an Alcatraz brochure.

Moutoux walks through the dim caverns of the old U.S. Army fortress – it was here before converting to the federal prison in 1934 – to an office that also serves as a break room. She checks out a telescope, tripod, clipboard, and a stack of island pamphlets.

Heading outside and up the sloping concrete pathway to the west side, she sets up to watch Brandt’s cormorants and black-crowned night herons’ nests in the bushes.

But it is cold and windy here and only a few tourists who have walked all the way around the 22-acre rock pass by.

“Two weeks ago, we had 30,000 nesting birds on the island,” she calls out to a fast-moving, puffing couple. “Now there are 20,000. Come look at a nest.” They smile and keep going. It’s the same with another couple.

Being a bird barker

“You’ve got to be something of an extrovert to do this job,” she said.

She packs up and moves around to the less windy east side, to one of eight docent-designated stations. It is a world of difference. Just below, hundreds of tourists are arriving at the dock every few minutes.

Heading for the cell blocks, tourists may first notice the Western gulls. They’re the noisiest and grabbiest for food. For this reason, some walkways have been closed to tourists, who are also advised to eat only in designated places.

Unlike other seabirds, who want the best food for their young, meaning fish, the gulls “will eat anything,” Moutoux said. “They’re the junk foodies, dumpster divers.”

They’re also the most aggressive in protecting their babies. When one of two falcons who make Alcatraz home flies over, the gulls’ incessant squawking escalates to a deafening level.

Visitors to Alcatraz sometimes have to be coaxed to notice the island’s other birds. With a telescope aimed at a five-foot-long, foot-deep great blue heron’s nest, one of six midway up a eucalyptus tree, Moutoux pleaded “Take a look,” to an on-coming pack. “The babies are peaking out of the nest!”

A family from Germany stops. “Wow,” says the dad upon seeing the heads of two babies above the nest that look to be two or more feet tall. As mature adults, they’ll reach four or more feet.

In her best voice over the next few hours, Moutoux invited tourists, mostly families, from France, the Netherlands, Italy, England, Wales, New Zealand, Canada, North Carolina, Idaho, Texas, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, “but no one from California,” she said drily, “not even San Francisco.”

Creating converts

As parents lifted their children to the telescope, Moutoux explained that the chicks would have to leave the nest in about a week, learn to fly, and start finding their own food. She surmised that the wind would knock them out of the nest and start the process.

Moutoux’s own child, a grown daughter now living in New Zealand, is less intrigued by birds, whom she says her mother spends more time with than her. But one of her grandsons has shown interest, Moutoux said. “I’m working on all of them.”

“Very cool,” said a Texas man at the scope. ”Thank you.” “How beautiful,” said his wife. “So big for babies.”

Adult herons – as do all nesting seabirds – return every year in February, just like they did before the Spanish arrived centuries ago. In two years, the juveniles will come back as adults to make their nests in the same eucalyptus tree.

The crowds keep gathering around Moutoux’s telescope. Language is no barrier.

Eventually, she estimated, she talked with more than 200 people that day. At the more accessible stations, like this one, it has sometimes been 400.

“Suddenly,” Moutoux said, “people realize that Alcatraz is not just about cell blocks.”

Seiko Grant

Great piece, very well done and I agree that it should be submitted to a birding magazine.

Geoffrey Link

Great story. Perfect for Senior Beat. Well reported, nice touch to the writing with lots of info and quotes. Should get submitted to a birder magazine as a wonderful light feature. Alcatraz is always a grabber and this one has an unusual twist with the knowledgeable docent.

Mary Ann Allan

What a great story! About a special place and a special person. And of course, about the birds. Thanks.