After the ‘food shock’ and a challenging beginning in U.S., Mexico City emigre finds her way back to her life of art

When Esperanza Villanueva arrived in Lake Tahoe from her native Mexico City in 1994, her hardest adjustment was to the food.

“That was a shock,” she said. “There was no food I liked here, not many Mexican products.”

She joined her siblings and their families who’d come years earlier and she laughs as she recalls an early incident. Her brother took her to the grocery store in Lake Tahoe where he lived and worked. He told her to get anything I wanted.

“I wanted a papaya to make a salad. We got home and he took a tiny little dried thing from the bag and laughed, ‘Here is your papaya,’ he said. That’s a papaya? I said. Not where I come from.”

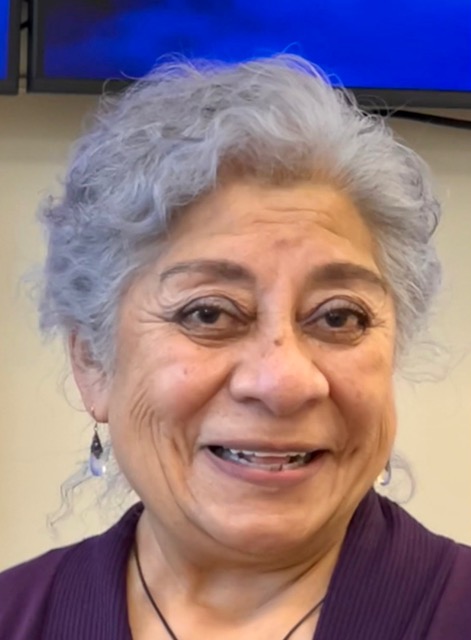

Villanueva, 77, is petite with deep-set dark eyes and wavy silvery hair. She dresses simply with an eye to color, showcasing her artist’s sensibility. An accomplished professional artist in Mexico City in her youth, she now teaches art part-time at the YMCA on Mission Street, the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, and the On Lok 30TH Street Senior Center. Her students range from age six to 86.

“Art has been my constant companion, my life partner,” she said softly, as she watched over a table of her students.

Thirty years ago, when her whole family left Mexico to work in California, Villanueva stayed behind to care for her niece and continue her career as an artist and art teacher in Mexico City schools. When the family was granted amnesty under a federal program in 1994, her three siblings asked her to join them in Lake Tahoe.

But it wasn’t easy to re-integrate back into the arts in the United States after leaving her life as an established working artist in Mexico City with a studio in her home, and commissions to work on public buildings.

Still, with amnesty and sponsorship in hand, Villanueva decided to join her family in the U.S. But her new life was tough and lonely, and her eyes filled with tears talking about it.

Her first job was as a babysitter. “When I came here, I had no English, and my sister suggested I hang up notices on bulletin boards.”

Rough start in Lake Tahoe

But she felt exploited by some of the families who hired her. “They left small babies with me until late at night,” she said. “I was stuck for long hours, and they didn’t pay me all they owed.”

Later, she worked as a room cleaner at the Nugget casino in Lake Tahoe, which she could walk to from her brother’s home. But she found the work “hard and demeaning.”

She bought art supplies and began creating art in her brother’s house. She approached the local schools to inquire about teaching.

“I already had my immigration interview and the legal right to work. I had all my diplomas translated and evaluated, but they just looked down their nose at me,“ she said. “It was humiliating. There’s less racism now, but then I felt dismissed.”

A woman she met helped her get a part-time job teaching art after school in a Boys and Girls Club. There, a dancer organizing a folkloric ballet enlisted her to paint the costumes and capes. She also mentioned the many opportunities for artists in San Francisco, which was experiencing a boom in mural painting.

So, after about a year, she told her siblings she was going to San Francisco to do an art job. “I didn’t tell them I wasn’t coming back,” she said. “I just left on the Greyhound bus at the end of 1994, and I’ve never lived in Lake Tahoe again.”

Growing up in Mexico City

Villanueva recalls a happy middle-class childhood in 1950s Mexico City. Her grandmother and parents ran a small fruit and vegetable stand out of their house, and her grandfather worked on the national railroad.

They had no television but gathered around the radio. Their favorites were a program that played whimsical children’s songs, and a ‘telenovela’ called “Leyendas de Mexico,” or Mexican Legends.

She attended local public schools, where in an art class she discovered a talent for drawing. “It came easily to me, whether pens, pencils, paints. Anything they put in front of me, I could draw – flowers, fruits, pots, jars, live models.”

Her mother died when Villanueva was 14, and as the eldest of four, she was expected to run the household, taking care of cooking, shopping, and cleaning.

“Now I look back and wonder how such a young girl was given that much responsibility. I was an adolescent, after all, but I dedicated myself to my family.”

A typical day meant leaving the house at 6 in the morning to get to school by 7 a.m., then a return trip home to prepare the family’s lunch, followed by three more hours of school. Sometimes she got up at 5 in the morning to hand wash their clothes.

Her secret joy was attending an after-school program at the Art and Design Vocational Institute “where I spent all my afternoons taking ceramics, silkscreen printing, jewelry making, and industrial design.”

She told her father she was doing homework in the library for those hours, and he never questioned her. She studied there for two years. Upon graduating from high school, she earned a certificate from the vocational art program as well.

Her father, she thought, would have argued that art school was a waste of time that would never lead to a decent living.

“When I got my two diplomas, I went to my dad and said ‘See, this is where I have been all those afternoons.’ He didn’t say anything at first, very reserved he was, and unemotional. Finally, he said, ‘OK, you will need to figure out how to support yourself. There is no inheritance or big money for you to be an artist.’”

Degrees in art

Knowing she was on her own, Villanueva went on to get a bachelor’s degree in visual arts and a master’s in mural painting. She lived at home and supported herself by teaching art part-time in the schools.

She was part of a team that painted a huge mural in tribute to all the races that populate Mexico. But it was destroyed in the Mexico City earthquake of 1985, a disaster that also changed her life

Her siblings lost their jobs as a consequence of the subsequent economic downturn and made the difficult decision to move north. Villanueva was left in charge of her sister’s daughter, 5-year-old Lydia Carmen.

Some five years later when her family urged her to join them, she moved to Lake Tahoe. “I brought my niece to join her mom, and I locked up the house, and just left. I was planning to return, but it didn’t work out.”

Villanueva stayed and worked in Tahoe for one year, then moved to San Francisco. For a few years after moving to San Francisco, she took a Greyhound bus to visit her family in Tahoe until that line was discontinued. “I haven’t seen them for a long time,” she said. More recently, Covid restrictions and her family’s busy work life have made getting together difficult.

She began her life in San Francisco renting a small room for $250 a month next to the Burger King on Mission Street. She moved eight times in 10 years, always renting rooms in marginal areas. “I was always worried about paying the rent, that was my big worry.”

She finally got an apartment on Folsom Street, where she still lives, through Mercy Housing for low-income families and seniors. She moved in on Sept. 15, 2015.

Independence Day

“That date is very important to me, because not only is it Mexican Independence Day, it became my independence day,” Villanueva said. “I finally had housing security and could work on projects I loved.”

Knowing no one in the city when she arrived, she stopped in to a church asking for work. The pastor suggested she try the Salvation Army, where she got a job arranging and sorting clothes. Determined not to lose her artistic life, she soon found her way into the local art scene.

Her first important contact in the local art world was Susan Cervantes, the director of Precita Eyes Muralists, with whom she painted the mural on the Women’s Building on 18th Street in 1994 and 1995.

She sorted art supplies for a summer art program for kids at her church and was able to earn a living teaching part-time in the Mission Cultural Center’s Art in the Schools program.

Three of her students won first-place awards in a Mexican poster competition, Asi Es Mi Mexico (This is My Mexico). “None of them could go to Mexico for the awards ceremony as they were all undocumented,” she said, “so the committee sent their prizes here, and we had a ceremony at Mission Cultural Center.”

It’s all about her students

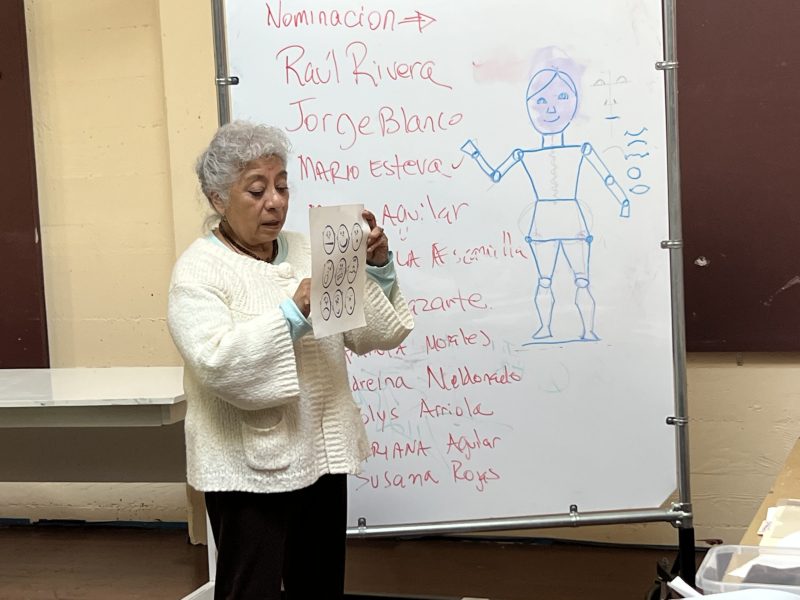

Villanueva oversees her students with patience, purpose – and humility.

“I bring postcards and calendars to give them ideas, then I start with the Chromatic Color Wheel,” she said. “I want them to understand colors; later I guide them to have their own ideas.”

When asked where she has exhibited her own artwork, she instead talks about her students’ group exhibits. “For me, it’s important that my students show their work, I don’t show my work with theirs, I want them to shine.”

She has never had a gallery represent her. “I am not good at promotion, I never had an agent or anything. I can’t do that.”

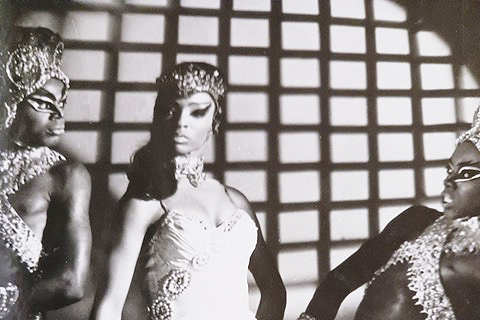

But a neat binder contains her artistic history: diplomas, certificates, commendations, photographs of paintings, etchings, drawings, scenery backdrops, and the many Carnaval floats she has painted over the years.

She has not been to Mexico to visit her numerous cousins in 15 years. But now, she is planning a trip to parts of Mexico she never visited as a young woman.

“I want to take a month to see Chiapas, Campeche, and I want to ride the newly inaugurated ‘Mayan Train’ that runs in a rough loop around the Yucatan peninsula,” she said, then with a big smile added, “I know I will be inspired there to create work I have not even dreamed about yet.”

Harriet Zisman

Great article. Strong woman. She is to be commended for her tenacity in never giving up and finally find a place to demonstrate her talents as an artist and skills as a teacher.