Deloris Perlmutter was only 20 years old when two young Cuban men selected her as the third member of their Wattusi Trio, a newly formed Afro-Cuban dance act that would catapult them to fame in the exploding international club scene of the ’50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s.

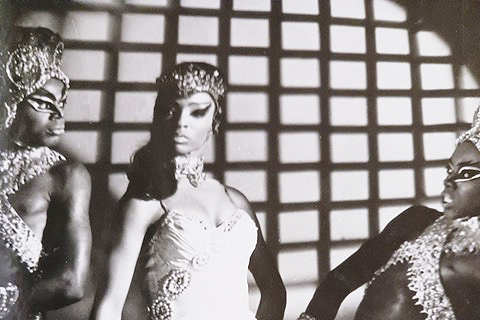

“Every club had its own house band. Acts competed to be the most elaborate and to have the most interesting original music and gimmicks,” she said. “We were over the top in presentation and costumes” – from bikinis covered with bright red spangles and bejeweled red crowns to colorful, robes and spectacular headdresses.

It was an era in which Africa conjured fantasies of the deep, dark jungle, a dangerous and unknown continent. Their act was drawn from a Tutsi tribal dance witnessed by Deborah Kerr and her safari guides as they search for her missing husband in the 1950 film “King Solomon’s Mine.” The movie dance, as was the Trio’s, is a derivation of the tribe’s actual dance. For one, only men participated in the actual Watusi dance.

Jungle fantasy

“We were after the fantasy, the fantasy of the danger, aggression, and exoticism of their movements.” In one routine, Perlmutter had to crack a whip over the two men and the audience. An animal trainer from Barnum and Bailey Circus was called in to teach her. It became one of their more popular acts.

About to turn 84, she no longer wields a whip, and her ankle is not in great shape, she said. But as a regular at dance exercise classes, like Zumba and jazzercize, around her Noe Valley neighborhood, she’s regaining her balance and strength. “Plain exercise doesn’t do it for me,” she said. “We’re born moving, and we want to keep moving.”

Most of her performing career was in Europe. She turned to teaching at the age of 35, settling in a small village in Spain with her husband and daughter. She moved to San Francisco just three years ago to be with her daughter, son-in-law, and grandson, with whom she’s become close. The two regularly exercise together. “He’s a football player,” she said. “We both use our bodies in what we do so we understand each other.”

And they’ll be watching Super Bowl LVIII together.

Perlmutter took dance lessons from the age of eight through high school. Her proficiency led to scholarships with the New York City Ballet, a move to the city, and a place at the prestigious Katherine Dunham Studio. At 19, she was selected as part of an avante-garde performance of dance and music led by Miles Davis and other jazz musicians.

The European embrace

She was at the right place and time to join the Wattusi Trio. In no time, they became stars in Europe’s thriving club scene. They opened for such headliners as Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., and Nat King Cole. They had their own publicist, manager, pianist and arranger. Candido Camero, a pioneer of Afro-Cuban jazz and innovator in Cuban drumming, toured with them.

During her 15 years with the Trio, they never performed on a U.S. stage. So beloved were they by Europeans that they made Spain their home base, first in Madrid, then Seville. They had planned to return to the U.S. after developing resumes that would open doors in America, but offers to perform in Europe kept coming in.

“Europeans had such respect for artists; they opened their arms. We would be about to leave, and there would be a contract from Denmark, from Morocco, from places we wanted to visit.”

Perlmutter was born in 1940 in Washington D.C., in the kind of neighborhood, she said, “where when one of your friends learned something, we would all run over to their house, and they’d show you how to do it.” One afternoon, after a friend demonstrated steps she had just learned in ballet class, Perlmutter immediately asked her parents if she, too, could take lessons. “A class cost a nickel, but that was a lot of money for my parents,” she said. “Yet somehow, they found it.”

Those lessons continued through high school when she received a scholarship from the New York City Ballet to attend their summer program. The following summer, the New York City Ballet awarded her a second scholarship. By this time, Perlmutter realized that she had to move to New York to realize her dream of dancing on stage.

Classically trained dancers have two career options: perform or teach, Perlmutter said. Though the NYCB appreciated her talent, she said, they were training her for the classroom. In the ’50s and ’60s, Black performers were not typically found on the classical ballet stage. There has been some progress but as recently as 2018, 21 ballet organizations felt the need to launch a project to advance racial equity in professional ballet.

Still, at 5-foot-five, Perlmutter was the right height and thin as any of the classical dancers on stage – and that’s where she wanted to be.

The Katherine Dunham Studio came into her life at the right time. Unlike many such institutions at the time, it opened its arms to Black dancers and trained them to be performers as well as teachers. A full scholarship allowed Perlmutter to devote all her energy to dance.

Dancing with Miles Davis

Dunham’s school was popular with artists in search of new talent. It didn’t take long before Perlmutter was recruited for the gig with Miles Davis. “First the dancers would create movements to accompany the rhythm of the great master’s music, and then Davis and the other musicians would add melody to the dancers’ movements,” she said. “Each show was based on pure improvisation.”

Those months, she said, were one of the most important things she ever did in her life and “the beginning of her launch. It was also the only time she ever performed on a U.S. stage.

Her next big break came a year later when the Wattusi Trio picked her out of 10 dancers who auditioned. “It was a pleasure to perform as an Afro-Cuban dancer – the stomping, the thrusting, the rhythm,” she recalled. “It connected with my energy.”

She stopped performing at 35. Married to a Dane in the hospitality business and the mother of a young girl, she settled in Estepona, a small village close to Seville. At first, she taught dance from her home, but it was not long before she opened her own studio down the street. “Help was not expensive, which made it easier to work,” she said.

After seven years, her family moved to London for her husband’s import business and to expose her daughter to urban life. While there, she offered classes at several studios, but primarily took care of her daughter and helped her husband with his business. The move and the business lasted only two years before they returned to the peaceful, small-town life of Estepona, where she reopened her studio.

In 2014, after her husband died and an injured ankle limited her ability to teach, Perlmutter closed the studio and retired. “I thought I’d stay in Estepona where I had many good friends, but my family began urging me to return to the U.S.” Most importantly, she wanted to be near her daughter and grandson in San Francisco. “I had never had an opportunity to be his grandmother,” she said.

Unexpected honors

But Estepona was not ready to say goodbye. The town had decided to honor her contribution to the community by naming a plaza after her. A crazy period followed, she said, with local papers as well as Spanish and dance magazines reporting the event. T-shirts, sweatshirts, hats, and umbrellas were sold. ‘Deloris red,’ the color of her Trio costumes and the nail polish she still wore, became a big thing in Estepona.

The ceremony and the “Deloris craze” that followed delayed her move to San Francisco, but today she is happily ensconced in her daughter and son-in-law’s Noe Valley home. While her daughter never connected to dance like her mother did, the two of them enjoy going to movies and theatre and renewing the mother-daughter relationship.

Noe Valley mirrors the warmth and convenience she experienced in Estepona, Perlmutter said. “The people are kind and friendly. It’s repeating the life I had in a small village. Everything is here. A great vegetable store, a pharmacy, school, the church, dance classes, and the 30th Street Senior Center.“

There are many Spanish speakers at the center, and its exercise classes are free. And, sometimes, an instructor will give her 25 minutes at the end of class to introduce some different movements. “The whole point of all this doing and teaching is to be able to share it with people.”

She envisions teaching again – gospel, funk and Afro-Cuban dance – when her ankle and energy are stronger. But just being able to share her memories with friends is reward enough for a “wonderful” life, she said. “I had a long and wonderful career. You put it out, it will be given back. The fact that you can touch peoples’ lives – It’s a gift.”