Painful college experience unexpectedly leads to successful career for man from Mississippi

Imagine having such a vicious toothache and no access to a dentist that you take a pair of pliers and extract your own tooth. Meet Chester Moody.

It’s 1958 in the Jim Crow South: Lorman, Mississippi, to be precise. He is 17 years old, attending Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, a historic black college. At the administration office, he is told it will be 21 days before a dentist visits the college.

In excruciating pain, he couldn’t wait to get written permission from his parents, which the school required to leave campus. “The only privilege you were allowed as a Black man was to know your parents’ name,” Moody said of the South in those days.

So, young Chester Moody broke into the campus woodshop, borrowed a pair of pliers, and performed his own extraction.

“It took me a while to get the courage, but the moment I clamped the pliers around that molar, the pain went away. It just dissipated,” he said. “I now know that it was the gas escaping, but I couldn’t walk around with pliers coming out of my mouth.” While screwing up the nerve to pull, there was a snap, and the top part of his tooth came off. “Oh, the smell was terrible but the relief was instant!”

Moody, who now has his own dental lab, on the 16th floor of the Sutter Street Medical/Dental Building in downtown San Francisco, has lived in the city for 60 years. Yet his speech still carries the thick cadences of his roots in Coffeeville, Mississippi, and his memories of the racism that prevailed in the South. Sturdily built with powerful arms and hands, he looks much younger than his 84 years.

“In those days, in the South, there were two professions open to Black men. You could be a preacher or a teacher,” said Moody, whose recollections are punctuated with easy laughs and a wide smile. He planned to teach industrial arts because, hey, he could sure wield those pliers. Dentistry had never entered his mind.

Three big breaks

Now, in life, there are all kinds of luck: dumb luck and blind luck, bad luck and good luck – and hard luck. In Chester Moody’s life, three against-all-odds–lucky breaks directed his destiny.

The first: After graduating from Alcorn in 1960 with an Industrial Arts degree, he went to St. Paul, Minnesota, to visit his aunt and cousins.

“Now, my aunt was taking my cousins to get their teeth cleaned and she said, ‘You come, too, Chester.’ This dentist did the exam after my cleaning and said, ‘Whoever extracted that back molar did a terrible job; he left the root tips in.’ I laughed and told him that was me.”

That dentist, Dr. Louie T. Austin, was the director of dental services at the St. Paul branch of the Mayo Clinic Health Services. and “he fell in love with me for my story,” Moody said. Austin offered him a job, and to train him in his lab. “He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself”.

“This guy was the greatest teacher in the world,” he said. “That’s where I got started, in the laboratory, and fell in love with it.“

Moody stayed with his aunt in St. Paul and learned the trade. Which is? Dental Lab Technology.

“I fabricate maxillary and mandibular removable prosthetics, which are inserted into the oral cavity for aesthetic and phonetic function, and hopefully to eliminate lactobacillus acidophilus,” he laughed, took a breath, and proclaimed, “In other words, I make false teeth.”

Moody worked for Austin for a few years, but in 1963 he was drafted into the U.S. Army. “I was going to defect to Canada, but my mom wept and wept and so, I said I wouldn’t go.”

And here comes his second bit of stunning luck. After finishing basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and three days before he was scheduled to be sent to North Carolina to learn artillery, his orders had been changed.

Young in San Francisco

Even today, his face beams with glee as he quotes his commanding officer, “Private Moody, you are going to San Francisco, to Letterman Army Hospital. They need a dental technician.”

He was so excited he said he stopped listening after ‘San Francisco,’ and immediately called his buddy, Jim. They had been planning a cross-country trip. “I said, “Guess what? I am going to San Francisco and my ticket is being paid by your uncle – your Uncle Sam!”

On the way to Letterman, he visited his family in Mississippi, then caught a train in Memphis, Tennessee, rode through Texas, and arrived in San Francisco in February 1963.

He lived in barracks at the Presidio, then an Army post, “Imagine waking up every morning and out your window, Your Window; you are looking at the prettiest sight you ever saw, the Golden Gate Bridge.”

Start with that view – out your own window, then being young in San Francisco in the 1960s. It was a glorious time in his life. On weekends, he and his buddies explored California. “We went north. We went all along the south coast. We went east. Oh, I was in the service, yes, but I was enjoying every minute of it.“

He always intended to return to Minnesota after his service, but he met his wife Georgette in San Francisco. “There were two ladies in the waiting room at the dental clinic at Letterman, and I overheard them discussing issues with their daughters. I went up and said, ‘Tell you what: You give me your daughters’ phone numbers and I’ll take them out and tell you what’s up with them!’

One lady sniffed, “No Way!” he said, but the other gave him Georgette’s number.

$75 a week

They met in February 1965 and were married that May. They divorced in 1980 and remain good friends. Their 15-year marriage produced three children, now in their 50s and living in the Bay Area, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandkids.

He got out of the Army the month he met his wife, rented a two-bedroom apartment on Golden Gate and Steiner for $135 a month, and got a job at the largest dental lab on the West Coast – “right here in this building, 450 Sutter, Pacific West Lab,” he said. “I was paid $75 a week. I told the owner I would only work there till the snow melts in Minnesota.” He grins and adds: “I tell people the snow never melted, so I stayed in San Francisco.”

Pacific West Lab was busy, with 100 dental technicians serving dentists in California and all of Hawaii, which had no lab. “Every Monday three gigantic mailbags arrived from Hawaii filled with dentures that needed fixing.”

And here comes his third stroke of great luck: A friendship with a co-worker that would last 60 years and would change his life.

As technicians at the Pacific West Dental Lab, Roman Braunfeld and Moody developed an instant rapport. On the surface, they could not have had less in common.

Braunfeld was a Polish Jew, a Holocaust survivor. He weighed 60 pounds, had tuberculosis and was almost dead when he was liberated from Buchenwald. One of the American soldiers who rescued him was a Black sergeant, also named Chester.

After recovering in sanitoriums in Switzerland, he moved to Geneva, became proficient in dental lab technology, and married. The couple emigrated to the United States in 1953. Working together at the Pacific West Dental Lab, he and Moody developed an instant rapport. When a mega-corporation bought the lab, Braunfeld left and in 1970 started his own, Far West Dental, a few floors above.

Moody stuck it out but got fed up when the new corporate ownership began laying off technicians and expecting the remaining ones to work faster and cut corners. He called his old friend Braunfeld, who said, “What took you so long?”

A lab of his own

By this time, Braunfeld had a thriving business. He also did pro bono work for those who couldn’t afford it, including recovering addicts who had lost teeth to drugs.

Moody sees his work as a public service but also an art. He remembers a 19-year-old patient, born with an extreme split in his upper lip, or a cleft palate. Despite multiple surgeries, he could barely open his mouth, making his speech difficult. Moody was able to manufacture an upper denture flexible enough to fold up into his mouth.

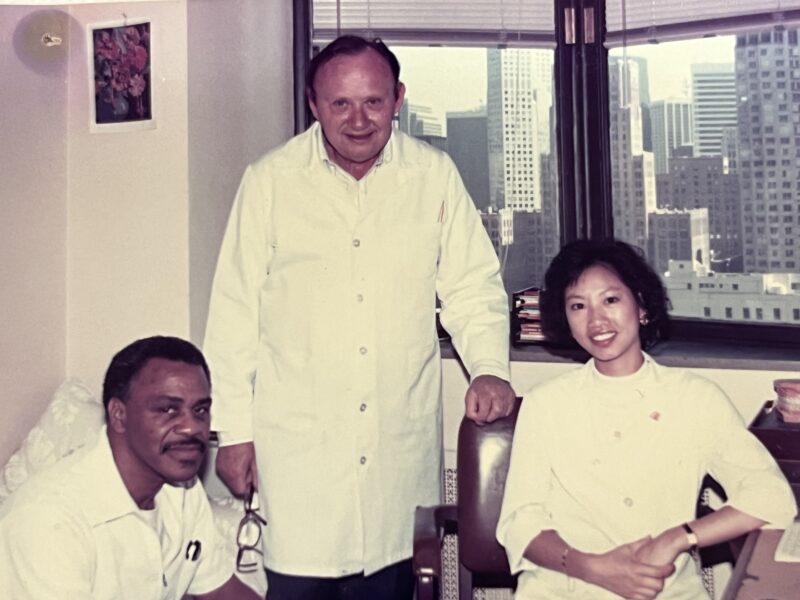

In 2006, Braunfeld sold the lab to Moody and his co-worker, Lily Louie, but remained working with them until he died in 2016.

Today, he and Louie work full-time and employ four to five people, but it’s harder and harder to find skilled craftsmen. City College of San Francisco once had a dental lab technician program. Louie graduated from it 40 years ago. Now, the only such program in the Bay area is at Diablo Valley College.

Moody said he has to retrain everyone, even new graduates, who can be slow, taking too long over each piece. “Even when I get graduates, I have to teach them to be productive.”

Today, Moody‘s small studio is an anomaly. The number of dental labs in the U.S. has declined as much of the work has been off-shored, mostly to China, Moody said.

Yet, the need to replace retiring workers here will continue to create about 8,300 openings a year over the next decade for dental and ophthalmic laboratory technicians and medical appliance technicians, according to the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics. However, demand for dental laboratory technicians may drop as 3D printing and other technologies are increasingly used to produce dental parts and appliances.

So far, Moody’s lab is still busy, humming and buzzing with the sounds of grinding and polishing. He gestures around the office when asked about retiring: “I am having too much fun to quit.”

Pointing to a breakroom table where boxes of Godiva chocolates, gourmet cookies, and other sweets join thank you cards from clients and dentists, he tells a visitor, “Help yourself; more work for me.”