Writing checks to pay the family bills doesn’t seem out of the ordinary. For most of us, it’s a monthly chore to which we don’t give much thought. For Virginia Cheng, that routine task is a symbol of recovery from a crippling auto accident and a measure of her willingness to lend a hand to her family.

Cheng, who is nearly 70, is partly paralyzed and needs a good deal of help with routine tasks. But she prides herself on being helpful and refuses to resent her physical limitations. “It’s part of God’s plan,” she said. “Gratitude” is a word she uses a lot.

Six-hour surgery

She’s worked hard at rehabilitation and with the aid of adaptive technology – enhancements to devices or technology to make it accessible to people with a disability – she can now use a computer, feed herself, and write checks. The checks she writes are to pay her family’s bills, a task she assumed soon after leaving rehab. Overwhelmed by the injuries to his wife, Cheng’s husband had let household bills pile up. Now they are paid on time, a step that Cheng says makes her feel like a contributor to her family’s well-being.

The accident that changed Cheng’s life occurred in 2007 while she was driving to her job at a San Francisco Unified School District childcare center. She was on U.S. 101 near Silver Avenue when an uninsured driver cut across three lanes of traffic and careened into the side of her car. She doesn’t know and says she doesn’t care what happened to the man who caused the accident.

Her injuries were extensive. “My neck was knocked out of place, my feet couldn’t move, the nerves in my fingers were damaged, and they didn’t expect me to ever speak again.” After a six-hour surgery at San Francisco General Hospital, she began arduous rounds of physical therapy and rehabilitation.

Recovering the use of her voice was her first challenge. She didn’t want a speech box inserted in her larynx. Instead, she did her best to speak naturally. Every morning she’d say, “Good morning, how are you?” She didn’t care if anyone understood her, she kept on using her voice, “I wanted to get a smile.”

One Saturday night, as a new nurse was taking her vitals, Cheng announced, “I have a voice.” But the nurse was busy and didn’t look up.

‘God gave it back’

She got a different reaction the next morning when she greeted her regular nurse: “She screamed and cried and called everyone in to celebrate. They wanted to know how I got my voice back. I told them, God gave it back to me. It’s amazing.”

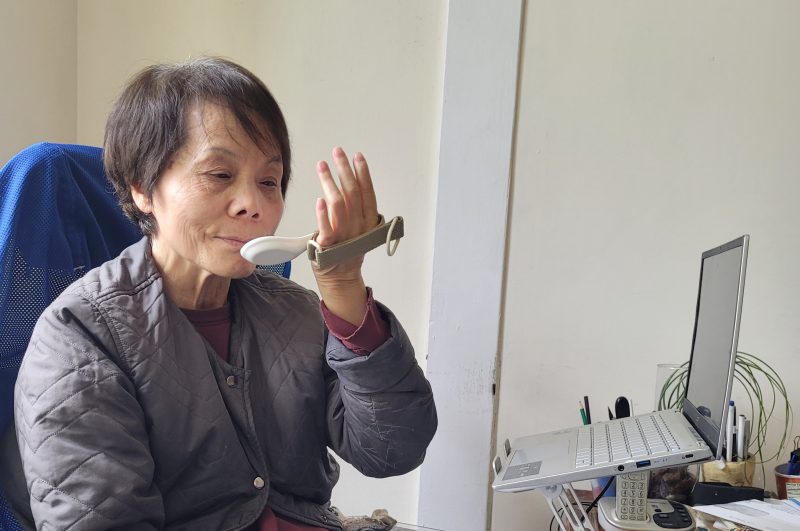

Seventeen years later, her speech seems free of the effects of the trauma. Her English is functional, but she’d like to improve it to have more sophisticated conversations. She’s become adept at using low-tech tools to control the movements of her hands. At mealtimes, she dons a brace and uses a weighted spoon to hold her hand steady. A strap holds her pen and a pointer affixed to her hand helps her type.

A native of Hong Kong, Cheng is a petite, energetic woman, dressed comfortably for sitting in a wheelchair all day.

She spends most of her time in a crowded, two-bedroom apartment in the central Richmond District. Her wheelchair is too bulky to easily move down the stairs to the street, so she rarely gets out. Although her life is physically restricted, she finds ways to enrich it, stay busy, and help her family. “I really enjoy myself now,” she said.

A caregiver comes in the morning and helps her exercise. She helps her out of bed and puts her in the wheelchair by a living room window overlooking California Street. Then it’s time to read the news on her computer, check email, and write checks. She and the caregiver chat and watch Chinese movies together. She attends an online English class once a week.

She’s able to use Zoom, chat, watch programs, and an iPhone thanks to an online technology class offered by the San Francisco Community Living Campaign.

When she first moved to the apartment after being released from rehabilitation, Cheng wondered what she would do with the rest of her life. She had always been a caregiver. Now she was the one being cared for.

She recalls noticing “a mountain of bills” or maybe it was just “a small hill of bills,” some of which were long overdue, and creditors were charging interest.

Now she makes sure the monthly bills are paid on time. She can’t bring in additional income, but she takes pride in saving money for her family.

Family comes first

Cheng has always had to work and help with family chores. When she was 10, she and her 9-year-old brother were responsible for all the housework in their Hong Kong home. Both her parents were working, and her two older sisters were already earning money, so it fell to the younger children to clean, shop, and cook. But there was little gratitude in return. “My parents never thanked us. They never appreciated our work,” she said.

When the family moved to San Francisco, Cheng, then a teenager, worked long hours in a succession of family restaurants. She studied English but dropped out because of the 12-hour days they demanded. “I wanted to earn money and help my family,” she said.

At her aunt’s restaurant, a busy place with long lines, she waited tables and answered phones. “I put my heart in the restaurant. I was tired after a long day, but I wanted to help my family.” But no matter how hard Cheng, her father, and her younger sisters worked, her aunt always called them “slow.”

After five years, her father opened his own restaurant in the Mission District. Cheng joined him, working the long hours she had become accustomed to. Marriage to a classmate she met when both were students in Hong Kong, did not change her work hours. Although her father was certain she’d want children and leave the job, she stayed on, assuring him she was there for him and the family.

After her father retired and sold the restaurant, the couple had three children, two girls and a boy. But she and her husband, Sherman Cheng, a plumber and handyman, couldn’t afford childcare, so he worked days, and she worked nights to support the family. Finally, she landed a good-paying job as a childcare worker for San Francisco’s school district, which ended with the accident.

Learning English

Cheng started attending church on Zoom during the pandemic. She now attends Bible studies twice a week. “When I’m depressed, it tells me what to do to calm down.” She even exercises her voice by joining the choir in song before the classes begin.

Last year, she enrolled in an English class for Chinese speakers. “My English was limited. I wanted to speak more than simple English. “Weekly classes offer an opportunity for her to learn new words, improve her pronunciation, and converse with English speakers. “My family likes that I’m learning English. Voila, it’s all good.”

Best of all, there’s Teddy, her first grandchild, not yet 2 years old. “Teddy is so smart. He’s no trouble. He loves to be read to. You put on his sleep coat, and he goes to bed without crying and sleeps through the night.”

But there are dark days. “Sometimes I don’t want to stay in the world because there are so many more people helping me than I’m helping.” But then she thinks of God and says, “I realize He must have a plan for me.” And she begins thinking of other ways she can contribute to her family.