Deborah Drysdale: social justice evangelist, bridge instructor, and amateur mixologist

Summers for Deborah Drysdale meant idyllic days at her grandparents’ cattle ranch in the Blue Ridge mountains of Virginia.

“My friends and I were ecstatically happy playing bridge, my grandmother’s favorite game, after riding farm horses, swimming in the river, and listening to “Oklahoma “and “My Fair Lady” on the record player.”

Home was Whitefish Bay, a suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where nothing much happened. She chafed at its small-town homogeneity, which she and her friends called “White Face Bay:” population 14,000, all white except for 22 Black residents.

They were both great influences on the person she would become: an “evangelist” for social justice – and bridge. Today, the 78-year-old retired family therapist is a teacher of the game and co-creator of an online instruction platform called Planet Bridge. She also works on the East Bay Community Foundation’s “race, gender, and human rights fund” and the Women’s Foundation of California’s social justice committee.

It was at Wells College in upstate New York that those twin devotions grew. “I played bridge all through college, there was always a game going on in the dorm.”

She was active in student government, pushing to make birth control available at the college health center. And she learned the real extent of racism in America on a one-week voter registration drive organized by her history professor. “Visiting North Carolina and knocking on doors in Raleigh opened my eyes to racism. Driving down, I saw chain gangs of colored men, and colored bathrooms. It wasn’t right.”

Fighting racism in New York

Back at Wells, she changed her major from history to political science to better understand racism. After graduation, in 1967, she took a two-year position with the Vista volunteer program registering Black voters in the South Bronx and East Harlem.

The late ‘60s were a volatile time. Young people began questioning American values and politics, making up the bulk of Vietnam War protesters. Though she described herself as “a minor player in the movement,” she was arrested three times. Released after her last court appearance under her father’s supervision, Drysdale briefly joined him in Oregon. It didn’t take long though for her to convince him she needed to “find her own way.”

After a brief sojourn in Santa Cruz, she moved to San Francisco, where she was hired as an abortion counselor at a local clinic. Deciding on counseling as a career, she enrolled at San Francisco State University. She got her master’s degree in Rehab Counseling in 1975 then a Ph.D. in Family Therapy from the California Graduate School of Marital and Family Therapy, now Alliant International University. Thus began Drysdale’s over-30-year career as a psychotherapist for families, couples and individuals.

Though her work, marriage and the raising of two children kept her busy, Drysdale found time to work on equity issues. She joined the social justice committee of the Women’s Foundation of California, where “a group of us finagled our way to the 2001 World Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa. We followed up by forming a group to talk about the lessons learned.” Later, she joined the donors’ circle of the East Bay Community Foundation, which was addressing prison reform issues.

In 2012, she closed her practice and “came back to bridge,” she said. “I didn’t want to wait till the nursing home to find bridge partners.”

Brushing up on bridge

She brushed up her game at a bridge class at Most Holy Redeemer Church in San Francisco. Neither of her two sons plays bridge, but, echoing her own introduction to the game by her grandmother, Drysdale’s eight-year-old granddaughter completed 13 lessons on a phone app, she said. “We’ve been playing Mini bridge online. Make my day!”

In no time, she began offering bridge classes in the San Francisco public schools and at local community centers. Online instruction, however, provided an even greater opportunity to grow the game.

Drysdale explored existing instructional platforms before teaming up with Indian software developer Amaresh Deshpande to fine-tune the platform he was working on. They had met in 2019 at a national tournament in the basement of the San Francisco Hilton. The result was Planet Bridge, a step-by-step approach for teaching the game both online and in person.

But the pandemic years were not the right time to introduce an online bridge program to adolescents. “With the schools closed, young people were over-Zoomed, unable to concentrate. They couldn’t handle another lesson on Zoom.” So Drysdale turned her focus to adults, training volunteers to help run Planet Bridge’s 24-week curriculum.”

How Planet Bridge works

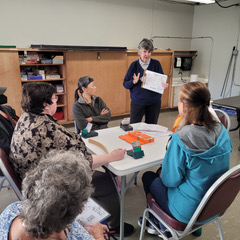

She has introduced Planet Bridge at the Coterie Cathedral Hill, the Chinese American Center and the Golden Gate Park Senior Center, as well as the Doelger Center in Daly City where she is currently teaching. A particular crusade of Drysdale’s is re-introducing “rusty newbies,” with shorter and perhaps fewer classes for players who were “traumatized by bridge in their youth and made to feel inadequate.”

Planet Bridge is a curriculum for teaching bridge. Each lesson addresses a particular theme followed by an opportunity to practice those skills. The new student curriculum covers such topics as counting winners, bidding, and making a plan in no trump, majors and minors. A sample curriculum can be found on their website. https://planet-bridge.org/curriculum

Building on her counseling skills and her belief that “socializing is the glue of bridge,” every session begins with a meet-and-greet. “I want to re-create that sense of a supportive, welcoming and safe environment where we help one another.”

Mistakes are seen as a learning opportunity, not a fault, and every session concludes with a game. Instruction is free, and Planet Bridge’s next beginner session begins on Sept. 3.

Friday evenings, she opens her Ingleside Terrace home to players from her many classes, both real and virtual. The evening allows newcomers to experience the camaraderie of the game. The “why did yous?” and “what ifs” flowed one night with 16 players, four at each of four tables, plus the inevitable kibitzers.

Phil Abrahamson, a competitive bridge player sat first with one table and then another, asking questions and giving advice. During a brief break for crackers and cheese, Pamela Resser, a relative newcomer, online learner, and soon-to-be empty nester, talked about a birthday dinner and online bridge game she shared with her mother in Chicago on Zoom. They ate the same meal before settling down to play bridge, said Resser, who lives in San Mateo. “I almost felt like I was there with her.”

One player had attended Drysdale’s classes last year with his parents at the Coterie. Tonight, his wife joined him. She had begun taking classes with Drysdale at the Doelger Center.

And there were others who were eager to share their stories. Though she had probably heard them many times before, Drysdale took pleasure in their retelling and in being surrounded by fellow bridge enthusiasts. “What could be more fun early on a Friday night than a “pick-up” bridge game? All we need is four players.”