Seventy-one-year-old Richard Marino is on the cusp of retirement. And it’s making him anxious.

He’s gone through other transitions, from coming out as gay, moving from his family home in the Bronx to New York’s East Village, and then leaving New York City for San Francisco. He traded a rambunctious gay lifestyle for a rather lonely professional life behind the information desk of the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library.

But the move into retirement feels different and difficult.

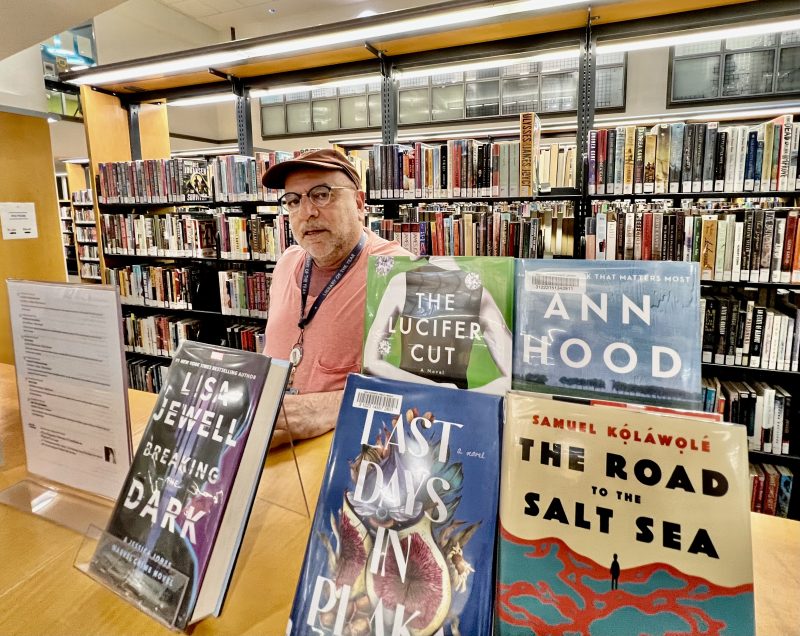

Marino planned to retire last June, but when the library assigned him to a job weeding out fiction books that hadn’t been checked out for five or more years, he decided to stay on. While his job title hasn’t changed — he’s still a library tech working under the supervision of a librarian — “it’s fun to play librarian and handle books.” The job should be finished by late this year, and he plans to retire next June. “It seems distant, but that’s only 10 months away,” he said.

Retirement looms

He wonders what he’ll do when the time comes. Will he be lonely? Will he be bored? He has some savings, and the library offers good retirement benefits, so finances don’t concern him — a notable change from his early years when money was a major concern.

“A job gives you stability, somewhere to go, and something to do,” he said. “Life without a job will be very different.” His brother assures him that he’ll be ready. “He told me, ‘You’re doing the right thing by exploring options’,” Marino said, counting those options on his fingers. “Writing my memoirs, acting, losing weight, and regaining my health.”

In 2014 he discovered a talent for writing when he joined Openhouse’s Gay Gray Writers group, where he has been writing his memoirs and getting to know other gay and lesbian seniors.

One of his memoir pieces was published in the Openhouse journal Write On! A second journal with more of Marino’s work may be coming out this fall. He joined the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) and had the pleasure of seeing two of his memoirs published in the spring 2024 issue of Vistas and Byways.

He enjoyed photography and painting when he was younger and may take art classes. A film buff, particularly when it comes to film noir, he’d like to join a film group. There’s a world out there for me to explore,” he concludes. “It might not be so bad.”

Early life in the closet

Marino was born in the Bronx to a close-knit Italian-American family. And even now, when all the family except his brother are dead, he misses those boisterous family dinners and card games. He would have enjoyed them even more if he didn’t have to hide his gayness.

There was that family dinner when his aunt blurted out, “Do you know what I saw on television? A h.o.m.o.” She spelled out the word to avoid saying it. “I don’t know why the network allowed those people to appear in decent peoples’ living rooms,” she added. Only his brother, wiser and always an ally, kept silent.

At 16, outed by a phone call overheard by his father, Marino came out to his family. “Your son is gay,” he said. After tears were shed by Richard and his parents, his mother looked for a therapist to “fix him.”

“Gay is not your problem,” Richard remembers the therapist saying. “You’re changing. You’re having an anxiety attack. You and your parents are deeply depressed. You need to understand your folks, give them time.”

After graduating from high school, Marino cashed in his savings bonds and rented an apartment near Christopher Street in the East Village, sleeping on the floor until his mother gifted him with a convertible sofa /bed.

Initially, gay life was as exciting as he had hoped it would be. Easy friendships, gay bars and dances, lovers and quick hook-ups, cross-dressing. “There was always something going on.” And, as someone on the street pointed out to him, “You have the security of an apartment to go back to.”

Leaving home was painful

Marino’s coming out years coincided with the AIDS epidemic ravaging the gay community. The combination of friends and roommates dying, the City’s cold winters and hot summers, and a nervous breakdown convinced Marino that it was time to leave New York. His older brother had moved to the Bay Area, and in 1983, Marino packed up and followed him. “Leaving my home,” he admitted, “was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.

He lived and worked in what he called a “fleabag hotel,” near the Civic Center. “For $5 an hour, I took out the garbage, broke up fights, answered incoming calls, and unplugged toilets.” He was able to supplement that income by working part-time answering phone calls at the much more upscale Hyatt, which eventually offered him a full-time job.

Neither the work nor his lifestyle brought much satisfaction. After considering his work options, Marino entered the library tech program at City College of San Francisco, where he earned a credential that enabled him to hold a full-time job with the San Francisco Public Library.

Job stability allowed him to move to a better apartment in the Richmond District. His first roommate was his widowed mother who had been diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease.) Marino and his brother convinced her to leave the Bronx and move into the new apartment with Marino where they could both take care of her. Although he had seen friends die, caring for his mother was the “most moving experience,” he said. “My brother and I cared for her until her death.”

As he aged, the gay life became less satisfying. Meeting people is particularly difficult for “an older gay male who is not sexually attractive,” Marino said.

The holiday season is the most difficult. Christmas was usually spent alone at a theater, watching old movies, and crying. While Marino is proud of leading a “unique life, not doing what others do,” he readily admits that he’s lonely. He’s begun to look for other outlets, like his newfound penchant for writing that might support him emotionally in retirement.

Finding his creative side

He had tried acting when he first moved to the Village, and though his onstage experience was limited to declaring, “the troops are coming” in “Caligula,” he recently joined the Community Living Campaign’s Zoom theater project Drama with Friends. His first role is as Danny, a depressed older man in the play “Where Do We Go?”

“Sometimes when I get depressed, I say, ‘Oh oh, I’m into the Danny character.’ It helps pull me out of that state.”

He explored photography in his youth, and he may return to it when he retires. Marino is a film noir aficionado and the library’s go-to person for film questions. “Perhaps I can join a film club,” he said.

And finally, there’s his weight. Marino joined a weight loss group at Kaiser that helped him lose 50 pounds; unfortunately, he regained 38. This time he’s built a support group — friends, co-workers, and his brother — to hold him accountable, and he is more confident that the weight loss will be permanent.

All in all, his outlook is beginning to brighten. “It might not be so bad. I have things I want to do, friends I want to see,” he concluded. He thinks he might even enjoy it.