Host of group that supports women forge new life after retirement fitting out her Dodge van to recapture the joys of childhood camping

It’s 11 o’clock on a Saturday morning and Janice Wallace is on Zoom hosting the Bay Area chapter of Women’s Connection, a national network that supports those looking for new life opportunities past retirement.

Wallace joined in part to make new friends. Her husband wasn’t all that social, she said. His main interest was collecting stamps. He also wasn’t much interested in camping, which comprised all her family vacations, and is something she has returned to since retiring.

Women’s Connection is based on Gail Rentsch’s book, “Smart Women Don’t Retire – They Break Free,” a guide with practical advice and stories of women who have redefined their lives. For Wallace, this has partly meant ramping up her social life and reacquainting herself with her childhood camping adventures.

After a year of grieving her husband, who died seven years ago, Wallace, now 67, said ‘yes’ to all social invitations, and immersed herself in volunteering. She dotes doted on the three sister cats she rescued three years ago and is retrofitting her shiny, new white Dodge Ram ProMaster into a camper van.

“I’ve been going on short camping trips in the Bay Area, starting to recapture those feelings from early family camping days,” she said. “When I’m up and running in my camper, I plan on going to many more.”

It’s all part of a re-invention that began when an 18-year career at Arthur Andersen accounting was felled by the accounting company’s conviction in the Enron scandal. The business dissolved and while caring for her mother, who developed Alzheimer’s, she hit on a new career: eldercare coach, which she did until 2015.

Love of nature

Wallace was born in Kansas City, Missouri, where her parents met working in a pharmacy with an old-fashioned soda fountain, just before her dad served in WW II. They married when he returned. Her dad’s insurance job took them to Scottsdale, Arizona, where she lived from five until 11.

Her parents made sure she and her sister, who was 10 years older, learned about the local culture, including the Native tribes. “I love the desert to this day,” she said. She was 11 when her father was transferred to Glendale, California. Her older sister, who had married, stayed in Arizona.

Family camping trips and Girl Scout outings imbued Wallace with a love of nature and its sometimes unexpected surprises.

“I remember one trip where my sister and I were tucked up inside our station wagon, and our parents were sleeping in a tent. Some kind of animal rubbed up against my mother and excitement ensued,” she said drolly.

Her recent camping trips have been more serene, and focused on “nature journaling, observing plants and animals, and drawing them.” She took a class in Pacifica and still meets with that group once a month. “We use apps for plant identification; it’s art and inquiry,” she said.

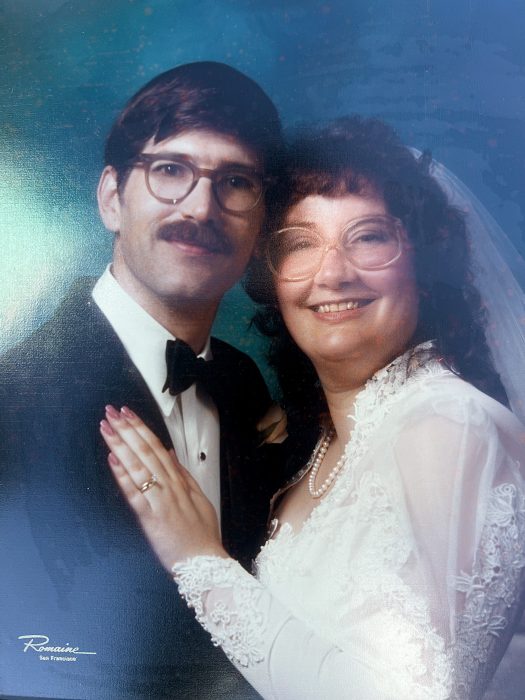

Camping went by the wayside when she married Bill, who she met through an ad in The Bay Guardian news broadsheet. “He was hotel all the way,” she said, “and I was kind of delighted – bathroom, shower. This is all wonderful.”

She had moved to San Francisco, where the insurance agency she was working for offered her a job. It “was a big turning point in my life because it was tough leaving my family and long-term friends behind, but “I found my husband here and I love the Bay Area.”

Stamping in Zimbabwe

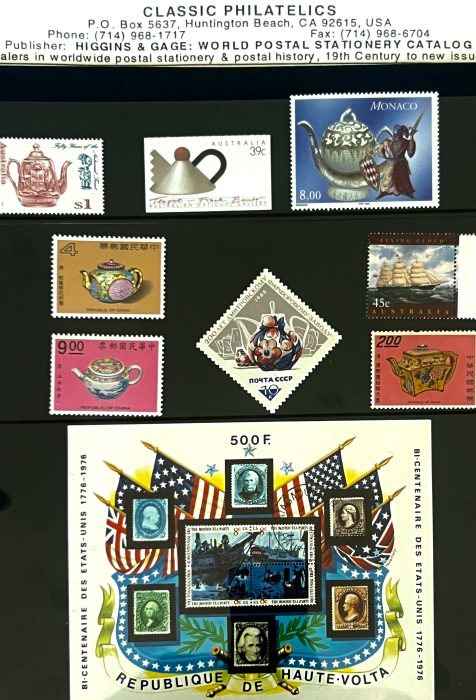

He introduced her to the esoteric world of stamp collecting. After their honeymoon in Western Canada, they headed to Zimbabwe to look for stamps from the colonial era, when the country was named Rhodesia. “We met with fellow collectors and did some stamp trading and buying,” she said.

“A particular interest of my husband was trying to collect postmarks of small rural post offices. Friends took us all over showing us the country and mailing letters from every small post office we could find,” she said. “We visited the only stamp store in the country in the capital Harare.”

Stamp collecting in itself didn’t particularly appeal to her. “Bill had suggested I collect cat stamps, and I tried for a while, but that wasn’t my passion,” she said. But being part of the collectors’ club was.

She’s still very much a part of the San Francisco-Pacific Philatelic Society. As board secretary, she produces its monthly newsletter, maintains the roster, and plans its annual holiday celebration. “Even though I’m not actively collecting, I’ve been friends with members for over 30 years.”

From her Girl Scout days to managing a corporate team to volunteer leadership roles, she has always thrived working as part of a team. She has hosted the Women’s Connection Zoom meetings for the past four years.

“After everyone checks in, we might discover that a member needs advice, or we may focus on a current event,” Wallace said of the weekly hourlong meetings. “The discussion varies but what is constant is we are very supportive of each other.”

She also leads the local chapter of “Together Women Rise,” a national nonprofit that awards grants empowering women and girls in low-income countries and is treasurer of her Toastmasters Club.

Her parents encouraged her to work while going to high school and college at the University of California-Los Angeles, where she graduated in 1979 with a major in social science and a minor in economics.

Path to leadership

She eventually got a job with Arthur Andersen, once one of the five largest accounting firms in the world, where she worked for 18 years. She started as a temp and worked her way up, running its employee technology help desk and tech training programs, becoming the first manager of operations.

“Both my mother, a bank officer, and my father were in leadership roles,” she said, “and I just imagined my work life would resemble theirs.”

But in 2001, the firm was convicted of obstruction of justice for shredding documents related to a federal audit of the Enron energy company, which hid from shareholders billions in debt from failed deals and projects. Although that conviction was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005, it wasn’t enough to save the damaged business.

The hardest thing Wallace said she had to do was lay off her team of 10 employees. “It broke my heart to see hardworking, great people lose their jobs for something out of their control.” The layoffs were so traumatic for her that, at 45, she vowed never to work in a corporate setting again.

Still, Wallace remembers it as a good place to work. At the time of Andersen’s demise, Wallace was also leading an international technology training program remotely in Singapore and Europe.

“It was a positive learning environment because as new technologies became available, employees were given the first opportunity at mastering them,” she said. “If it wasn’t for the Enron debacle, I would have stayed there for my entire career. I loved the people and my work.”

New challenge, new career

Although the layoffs and losing her job shook her to her core, Wallace called upon an inner reserve as her mother began to display symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. “She was repetitive, but we thought she was just depressed from not working anymore.” After a crisis where her mother spent two weeks in a psychiatric ward, the family placed her in memory care in an assisted living facility.

The experience revealed what she saw as a need for help through unfamiliar and challenging territory.

“People, like our family, were lost trying to figure out what to look for in a facility and how to deal with management,” she said. “My father got angry at the facility’s directors when things went awry, and I explained to him you get better results when the authorities are on your side.”

She calmed things down by relying on her corporate team-building skills. She began working with a coach, then decided to train as an eldercare coach herself. She networked with people in the care community and joined a business networking group.

Coaching aligned with her longtime interests and values: working with people, problem-solving, guiding clients to self-reflect, and helping them make good decisions. She coached adult children and spouses of the elderly for 11 years, closing the business after her parents passed.