Sixty years later, a writer returns to her childhood home in Mexico and savors the sights, smells and flavors of a changed San Miguel de Allende

Have you ever wondered about retiring to Mexico?

Not me, no expat life for me. But I wondered how it would feel to go home to Mexico again. More than sixty years after leaving, I spent October in my childhood town of San Miguel de Allende, in the central highlands of Mexico.

In an amazingly original move for the time, my parents took us out of our safe Northern California bubble, out of school, away from our pals, and drove us in a blue VW van through Mexico to San Miguel. I was nine years old. My siblings were six and three.

We stayed for more than four years.

Like Brigadoon or Shangri-La, San Miguel de Allende, at 6,200 feet above sea level, appears like a mirage out of the clouds. Its church spires and bell towers pierce sapphire skies studded with frothy clouds, the mild air kisses your skin, and the sun is gentle as warm honey.

After my husband and I arrived, I asked expats at Kenny’s Place — a bar owned by Kenny from Indiana – why they moved to San Miguel. Several replied that they had Googled “best weather in the world year-round” and the search engine returned San Miguel and Nairobi, Kenya.

Famous for its expatriate “gringo” community and its glorious climate, it’s no longer a cheap haven for dreamers, writers, and artists, many of whom arrived in the ’50s and ’60s. The G.I Bill paid for young veterans to attend Spanish and art classes at the newly established Instituto Cultural de Bellas Artes, and they flocked to San Miguel.

My dad, a writer, found a rich community of artists from Europe and the U.S. there in the early ’60s. Today’s San Miguel’s “gringos” – a non-pejorative term frequently used by Mexicans and many expat Americans — are those who may have learned about San Miguel in glossy magazines like Travel + Leisure, wealthy retired business people, and lots of Texans.

As soon as we walked into our rental house, the scent of San Miguel came back in a flood. We inhaled the smell of cool adobe and gas in the kitchen- that particular Mexican cooking gas odor blended with adobe/clay and straw.

Smells and tastes of home

Then the sweet fresh smell of the brief afternoon deluge: the sudden rain on the dusty stones, the sky darkening like an ink bottle turned over and spilled. The sizzling smells of braziers charring meat, chilies, tomatoes, and onions, smells that grab your nose aggressively as you walk by.

But beware of those mouthwatering smells, and rue the day you eat from those street vendors! My mother, who grew up in Shanghai and knew about dysentery, forbade us to go near those stands.

But eating fresh tortillas from the tortilla factory — the charcoal/hot corn scent like perfume — that we were allowed. And oh, how fine those tortillas tasted 65 years later.

Here comes the hail, brief and huge. Here is the light that my dad called Christ Rays, the sun slanting down in streaming golden pockets, anointing a block, a house, a park, in a brief radiant canopy.

I wanted to revisit my school, the two houses we’d lived in, the bullring around the corner where I saw many bullfights, the Instituto Bellas Artes where I learned classical guitar, the hot springs where we had splashed many an afternoon away, the ice cream shop where I’d first tasted coffee ice cream.

My little girl brain took the elderly Naomi through the streets she’d skipped along, only now I stepped cautiously on the cobblestones. I remembered our address. We’d lived at 11 Calle Huertas. Our steep block was unchanged from 66 years ago, and I was thrilled to see our green gate was painted the exact same color.

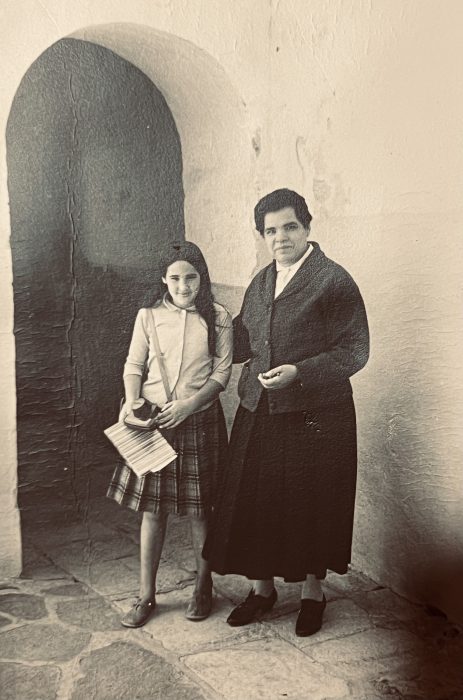

When I knocked, the now 96-year-old landlady and her caregiver opened the door. That landlady remembered el Senor Marcus “con la barba, verdad?” (with the beard, right?). We laughed as I showed her photos of us in her house in 1964.

The patio, the stairway, the plants, all the same. However, the comfortable house had been remade into three apartments, all Airbnbs run by her daughter. “Todo cambia,” she said, (everything changes).

I attended Escuela Santo Domingo, a private school run by an order of Catholic nuns. They called me “La Israelita” due to my Jewishness. During my first month there, the nuns kept bringing me to the chapel to convert me, but I always cried, till my mom stormed up the hill to the Madre Superior’s office and declared, “No mas! No conversions!”

We wore navy blue uniforms and marched in all the Mexican national holiday parades. Old Naomi wandered the playground where kid Naomi learned to march in formation (mom not too happy about that either) and sing patriotic songs.

I remember the catcalls, men calling out after me as I walked home from that school, even at age 11. “Ay mamacita, mamacita” (hey, little mama.) It was annoying but not scary. It got worse as I turned 13. Now, men on the street respectfully step aside for me to pass.

I saw no American kids at my alma mater, and I learned there is now a private Waldorf school in San Miguel de Allende. Like San Francisco, it appears there are more dogs than kids. The Mexicans who support the retirees and the tourists, mostly live in outlying villages.

As I wandered through the Jardin, (Central Square), I heard the ancient beggars wrapped in their rebozos calling out from the same corners as 65 years before, their pleas blending with the endless church bells.

While visiting the converted 17th-century convent where I learned classical guitar, I watched bustling art classes in the bougainvillea-sprayed courtyards where retirees sculpt, bronze, weave, and cast. They spin pots, paint, and sketch. Dressed in the San Miguel retirement uniform of baggy shorts, huaraches, and floppy colorful straw hats to protect their Northern skin, they appear prosperous and cheerful, like Kenny who runs the bar.

The expat life

When I was a kid, the directory of foreign residents was a mimeographed hand-bound volume called The Juarde directory, pronounced “whoaredey.”

Now, of course, there is a Facebook page for expats and one for potential expats, a Facebook page for the local yoga people, and one for the vegan people.

I visited friends, a young Bay Area couple who’d just moved to San Miguel with two sons, 5 and 3, both in the local Waldorf school.

Back in San Francisco, these digital nomads had queried me about our family’s San Miguel experience, as they were thinking of doing the same, and I’d encouraged them.

They’d had a rough entry as the boys got sick the first month, but a US-trained Mexican pediatrician (they’d bought a local medical plan) made a house call at midnight for $30, treated the boys with medicine he brought, and reassured the parents.

In 1965, when a scorpion bit my sister, our housekeeper Vincenta laughed at my mom’s fear, sucked the poison out of my sister’s chubby arm, spit it out, and said, “No es nada, Senora, no es nada.” (It’s nothing.) Then she rubbed a garlic clove on the wound. That was the end of that.

This couple was in awe of my parents’ pre-internet bravery: How did they know about schools? How did they find a place to live? How did they think about health care? How did they learn Spanish? I had no idea, but my parents never seemed daunted.

My parents hired an elegant, retired physician to tutor them in Spanish at home every afternoon in our courtyard, and they were fluent in six months. But they really wanted to speak well. When the couple told me they were studying Spanish online, I was appalled, “Are you kidding me?” I spluttered, “You are here in Mexico, get a tutor!”

I have no statistics on how many of the San Miguel expats speak the language, but my fluent Spanish has been my parents’ lifelong gift to me and my siblings. Gracias! (Estimates are that upwards of 10% of San Miguel de Allende’s 174,000 population are expats.)

At age 13, I took drama and Spanish classes at the Instituto Allende, a private arts school that had no problem letting a precocious teen pay to attend.

To my chagrin, Instituto Allende, though still offering a range of studio art classes, is now mainly an expensive wedding venue. When I made the pilgrimage to my favorite classroom, a cleaning crew was there gathering dozens of discarded bouquets, corsages, and centerpieces.

I asked if I could have one bouquet, and they pushed a bunch into my arms. The classroom and little theater where I recited passages from Shakespeare and Cervantes are now used for weddings, birthday celebrations, and other events.

Kid Naomi liked drama, and maybe that’s why she loved bullfights and went often, paying extra pesos for seats in the sombra (shade) instead of in the sol. She even hung around after to watch them slaughter the dead bulls.

Now, here at the bullring, my husband asks Old Naomi, “How could you stand that? Didn’t you feel bad for the bulls?” Correct, Old Naomi wouldn’t go to a bullfight today. She has evolved.

Mansions replaced art studios

What was astonishing was how much I remembered; how little the town had changed physically, yet how enormously the expat population had changed. Instead of art studios and ateliers, people build mansions and monster homes and shop in fancy grocery stores as elegant as any Whole Foods in San Francisco.

In the ’60s we carried a basket to the open-air produce Mercado and patronized the only Super Mercado run by the spinster Sanchez sisters.

Ah, how thrilled we were when they began to carry Cheerios and Frito Lay Chips.

Old Naomi could never live there now. My parents could never live there now.

But Old Naomi came home with a lot of compassion and respect for Kid Naomi; how well she managed the machismo, how well she navigated adolescence in a new country, and how many Mexican songs she learned to sing and play. Really well.

Old Naomi came away with a new respect for her parents’ bravery and fortitude. How I wish I could tell them that now.

Shari Morgan

I LOOOOVE this article Naomi. I feel like I was right there with you. You truly have a wonderful flair for writing. Thanks so much for sharing with us!

Gianna DeCarl

Another great piece by Naomi Marcus. I was transported to beautiful San Miguel by her vivid descriptions. I loved the juxtaposition of Kid Naomi and Old Naomi (and the perfect photos). She was so lucky to have lived there in the 60s!

Dominic Martello

Wonderful memories, I can almost smell the air. The scorpion episode was a little shocking and I'm so glad you've evolved bullfight-wise. Ole!

Melanie Grossman

Engaging and well written! Love the way the author made both the past and the present come alive!

doris bersing

This piece was incredibly moving; I felt like I was right there with you. Your voice shines through so clearly that made me reflect on my own experiences and the importance to come to terms with our life events and inheritance, as we grow older. Your essay is a masterpiece of personal writing and you really, have a gift for making the ordinary feel extraordinary. Well done and the photos are beautiful, as well. This is a testament to the power of personal storytelling. I am craving for more like this!

judith greengard

They always say that you can't go home again-- the amazing thing is that naomi found so much to be the same!