With more than 28,000 movies and TV shows on hand, Colin Hutton’s Video Wave store has survived the onslaught of Netflix and Amazon Prime

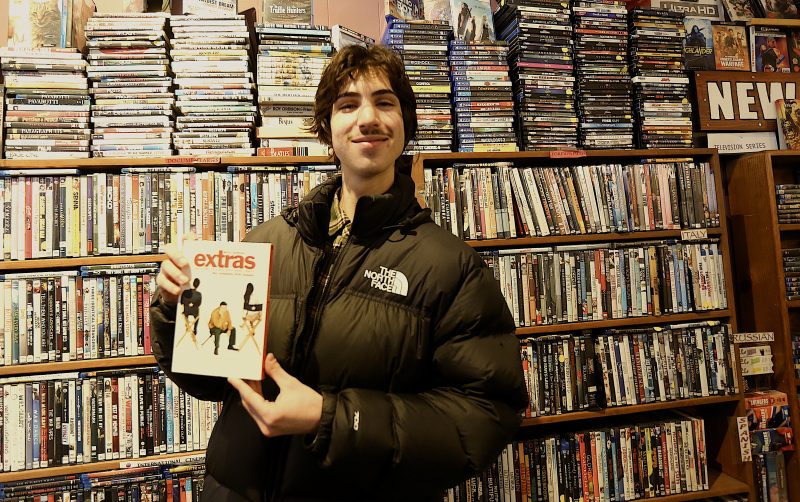

It was a rainy winter afternoon, and it wasn’t until Video Wave, the last standalone movie rental store in San Francisco, had been open for about 30 minutes that the first customer wandered in. A young man named Mateo looked around and quickly spied a copy of “Extras,” a collection of episodes of an obscure Ricky Gervais series.

“I used to watch this with my dad, but I haven’t been able to find it anywhere,” he said before buying the DVD. “I just stumbled on this place. I love stores like this.”

Score one for Colin Hutton, who has owned Video Wave for about 20 years and has survived the onslaught of streaming giants like Netflix and the never-ending evolution of video formats. “We have things that aren’t streaming and will never stream that you won’t find on Netflix,” he said.

That’s not just a boast. His tiny Noe Valley storefront is crammed with 28,527 movies and television shows on DVD and even VHS, roughly five times more than are available on Netflix, according to Justwatch, a marketing company serving the entertainment industry.

For Hutton, 56, the store is more than a living. It’s a mission, a way to preserve “our shared cultural history. Movies are stories; people should have access to as much of our storytelling history as possible,” he said.

Fulfilling that mission doesn’t come easy. Video Wave is a solo act that generates just enough income to stay afloat. The store is open five days a week. But there’s plenty of work to do when it’s closed. His work week is about 60 hours, not including time spent watching movies.

Plentiful screen time bolsters his deep knowledge of films, a big selling point. Hutton offers personalized film recommendations to customers, a level of service that Netflix, Amazon Prime, and other streaming services that rely on algorithms can’t match.

Not that watching movies is simply a chore. “I’m a movie geek,” he said. Hutton was raised by a single mother who loved movies. “She would take me along, and I probably got to see a lot of movies I really shouldn’t have seen,” he said, recalling a probably inappropriate Richard Pryor film he saw as a kid.

Running lean

His precocious exposure to film turned into a lifelong obsession. His tastes are eclectic. “Movies are a mood thing.” Depending on his mood, he’ll watch action, suspense, or comedy. “I even like Marvel,” he said. Does he have a favorite movie? “Not really.”

Video Wave is about as lean as a business could be. The 24th Street storefront has no heat, no employees other than Hutton, a munchkin-sized bathroom not open to customers, and only one chair. Every available space is crammed with DVD and VHS boxes. One of the clocks on the wall is broken, and his computer system is a relic. The software, he said, is more than a decade old; the laptop that runs it is even older and not connected to the Internet.

Video Wave is one of the oldest businesses in Noe Valley and has survived the neighborhood’s gentrification and the turmoil of the pandemic years. “People care about Video Wave; they want it to remain in the neighborhood.” More than once, he’s resorted to a GoFundMe campaign to get through a rough patch.

Like a streaming service, Video Wave runs on a subscription basis. The monthly fee is $8, which includes one free rental. Additional rentals cost $6 to $8. Some of his customers rarely rent a movie but continue to make regular payments. It’s their way of supporting the store, Hutton said.

The subscription fees generate a predictable, though sparse, income stream. He lost subscribers during the pandemic shutdown and now has just 520. He’d like to have 600 or 700. It can be nerve-wracking, he said. “Some months I lose money.” And rebuilding the customer base from the pandemic’s decline is slow work. Even Mateo, the San Francisco State student who bought the Gervais DVD left without becoming a subscriber, Hutton said later.

Hutton wouldn’t look out of place as a department store Santa. He’s tall, with a full white beard, glasses, and a bit of a paunch. A native San Franciscan, he grew up in the Avenues and went to George Washington High School. He did his undergraduate work at the University of California, Santa Cruz, followed by graduate studies at San Jose State University, where he earned a master’s degree in library and information science.

Never married and an only child, Hutton lives in Park Merced. When he’s not working, he enjoys cooking, playing video games, and listening to music. He rarely streams video. When he does, he’s evaluating content that one of the services is likely to make available on DVD.

He worked as a reference librarian at the San Francisco Law Library for about 10 years. But there was little opportunity for career advancement, and by the early 2000s consolidation of the library’s three branches and possibly layoffs were looming. His girlfriend at the time wanted to be her own boss, so they explored buying a business. Video Wave, then a few blocks away from the store’s current spot on 24th Street, was for sale, and the couple bought it for $80,000 in 2005.

From VHS to streaming video

There were dozens of video stores in San Francisco at the time, but the rental business was on the cusp of major changes. VHS had long since vanquished Betamax as the dominant format, but by the early 2000s, DVD was rapidly gaining popularity. Hutton and his partner needed to upgrade Video Wave’s aging inventory soon after they bought the business.

Even though they take up a lot of space, Video Wave still has 3,200 VHS tapes on the shelves. They’re still popular with some young aficionados who dislike DVDs, although there hasn’t been a new movie released on VHS for about 20 years, Hutton said. Older customers tend to be rather eclectic in their tastes, but Oscar season is always busy and nominated movies fly off the shelves.

Not long after Hutton and his partner – she is no longer with the business – took over Video Wave, a new format arrived, one that would eventually destroy the video rental business: streaming media. Netflix, which had been renting movies by mail, began streaming a few titles around 2007 and was later joined by Amazon Prime, Hulu and many more.

By 2015, San Francisco’s best-known video store, Le Video, went out of business and transferred its collection to the Alamo Drafthouse theater. And in 2023, Netflix finally ended its rent-by-mail business. Seattle’s Scarecrow Video, reputed to be the largest remaining movie rental business in the country, recently told its customers that without substantial donations it may well close its doors.

Asked if Scarecrow’s troubles are a bad omen, Hutton shrugged and said: “We’ve had lots of bad omens.” He believes Video Wave’s customer service and quality – DVDs offer better resolution than streaming platforms, he maintains, will keep customers loyal. “Streaming services are the worst part of the Internet. You have no control. We offer something much better.”

What about retirement? “Nope. I expect to keep working until I die.”