Things of heaven and earth – but mostly earth – have captivated neuropsychologist who once pondered the priesthood

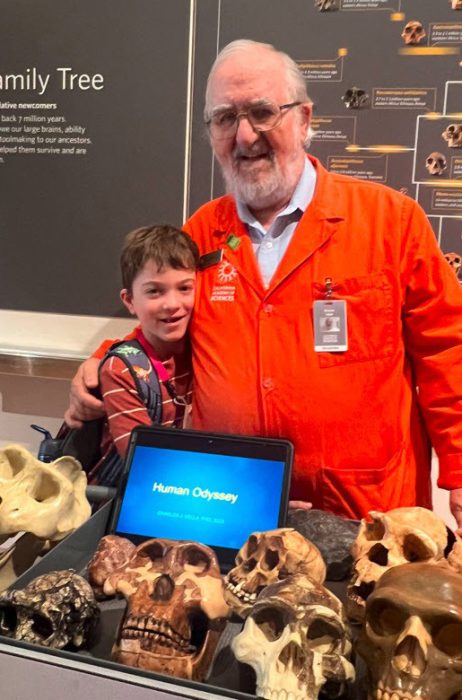

When he retired in 2009, Charles Vella began volunteering at the California Academy of Sciences. He became known as the “amateur paleontologist.”

His first volunteer job was sorting freshwater snails in the basement, which he did for a year. Then with a week’s training, Vella became a docent for the Evolution Group on the main floor.

“I stood there for four hours, with my display cart of skulls from Neanderthals and other hominid species that lived before Homo Sapiens,” he said, “and talked with people interested in human evolution.”

Aside from his current attraction to paleontology, the study of life in the geologic past, he has 3,000 samples of minerals and a collection, begun in childhood, of 5,000 stamps from the U.S. and his ancestral Malta. He also has gathered a database, the only of its kind, of Maltese immigrants to the Bay Area. His family genealogy project has more than 100,000 names. He also has preserved in photos the hundreds of intricately carved pumpkins his family and neighbors have created over the Halloween holidays.

A self-described “autodidact” who is “mildly obsessive-compulsive,” he is rarely bored. He “loves to stay intellectually busy” and is always in learning mode, amassing and organizing information.

But as a teenager, Vella took a chance at service to the divine. Growing up Catholic, he was encouraged to join the priesthood. After attending a seminary high school, he became a Franciscan novitiate, donning a habit, tonsuring his scalp, taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and enduring long periods of silence.

He completed seminary college but left the order at the age of 25. Earthly interests had prevailed. He had fallen in love. But he had also bristled at church conservatism and its belief in the afterlife.

Turning to psychology

A lecture by an admired Rabbi convinced him that his moral and ethical behavior did not depend on believing in Heaven. And, he was unhappy with an order to him and his fellow seminarians to back off from investigating discriminatory housing conditions plaguing African Americans. “In my senior year in seminary college … “the conservative Archbishop told us to stop political organizing,” he said.

And on a practical level, he felt unequipped to help teenagers with significant psychological issues that were in the adolescent group he oversaw. So, he turned to the field of psychology.

“It was also a way I could help others, and my theological training taught me that in helping others I created a meaning for life,” he said. “I still believe that is fundamentally important.”

Vella began working as a licensed clinical neuropsychologist at Kaiser Hospital, San Francisco, in 1978. He was Chief/ Psychologist/Behavioral Health Manager II from 1988 until retiring in 2009. He was also the founding director of Kaiser’s Neuropsychology Service, which conducts psychological testing.

Although Vella’s first romance fell apart when it became long-distance, in 1972 he married Marilyn Uran, whom he met on a blind date. She’s a quilter and “great cook,” he said. “I am the baker and dessert specialist.” They have two daughters, one a clinical psychologist, and the other a cardiothoracic radiologist. “My family has been the center of my life,” Vella said.

Vella’s parents emigrated to San Francisco’s Bayview District from Malta, an island country in Southern Europe, in 1950 when Vella was five. “My parents learned English in Malta and didn’t require my three siblings and me to speak Maltese at home when we emigrated, so within a year I was speaking exclusively English,” he said. “But I can still count to 10 in Maltese.”

The Vella’s resided in a large community of Maltese in the Bayview District. His mom worked as a seamstress for R. Spear & Company, becoming a foreperson. She produced a 1993 YouTube video making Maltese pastizzi that garnered 9,000 hits. Vella’s dad was a jack-of-all-trades, specializing in metalworking.

In 1962, while he was in seminary, his parents moved to San Leandro where they lived for the next 40 years.

At 80, Vella’s energy is boundless. Although he was the family’s oldest child, he is the only one left of his three younger siblings.

Maltese ancestry

One of his more recent projects is the Maltese Immigration to the San Francisco Bay Area database. He began it upon discovering the San Francisco Maltese Club had a Historical Society. He can trace his surname, still one of the top four in that country, back to 1600. The database now has over 13,500 names.

“I enjoy compiling all the fascinating historical tidbits,” he said. For example, Maltese American John Pass helped John Stow recast the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia in 1753 after it first cracked. It’s inscribed with their names, “Pass and Stow.”

Vella got the genealogy bug in 1982 when, after purchasing his first IBM computer, he input his wife’s grandmother’s family history, which she had compiled in the 1950s. It’s now 36,000 pages long, with 103,778 names at last count.

Another of his projects, started 40 years ago, is a mineral collection that includes Aegirine, orange with gold and cream; Amethyst balls, lavender on a bed of gold; Apophyllite-Stilbite, white on white; and Aragonite, a creamsicle color. Several decorate the fireplace mantel in the living room and the shelving on his front porch. The rest are stored in 80 scientific specimen boxes in his basement. “I take some out at every opportunity and show guests.

In retirement, while a docent at the California Academy of Sciences, he enjoyed paleontology so much that he took several online courses, read dozens of books, and subscribed to pertinent periodicals. He continues to review all the new major research articles on human evolution. He gave talks to other docents, and when COVID-19 hit, he created a once-a-month Zoom class on evolution.

He also created a five-week class on “The Brain and Its Functions,” and one on “Pre-Homo Hominids like Lucy” at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute in San Francisco, where he had taken classes. He also leads its Human Evolution Interest Zoom Group on the 4th Wednesday of every month.

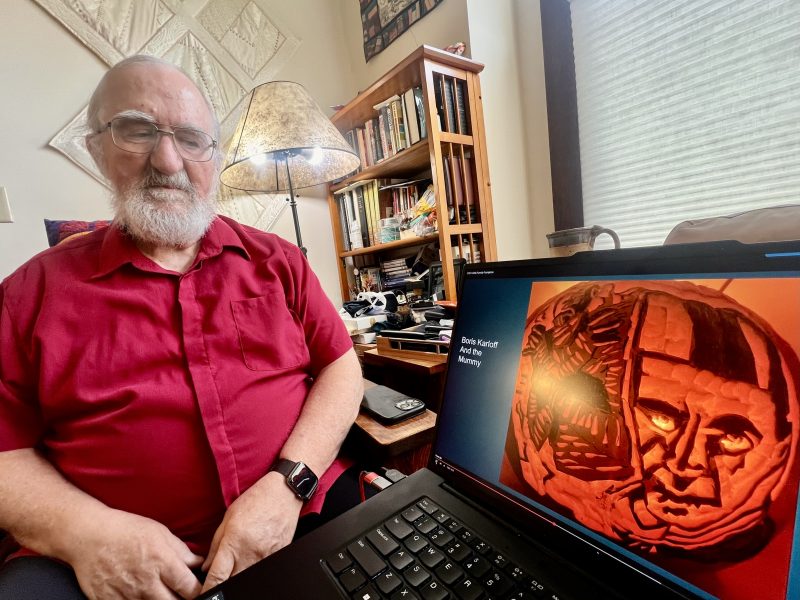

Pumpkins galore

Closer to home is the Vella family pumpkin carving tradition, begun in 1995, which has made them Halloween celebrities in their Glen Park neighborhood. “Last Halloween, I stopped counting after 1,500 people walked up our street to view our pumpkins,” he said.

Various family members, friends, and neighbors pitch in to carve more and more pumpkins each holiday. For Halloween, 2024, the Vellas displayed 175 votive-lit and Christmas bulb-lit pumpkins, 40 real and 135 foam. They began adding very realistic-looking foam pumpkins five years ago. One advantage: he’s able to save them over the years.

Foam pumpkins are carved with a Dremel drill. Real pumpkins are carved with sharp wood carving tools, four days in advance of the big event to avoid mold. They began as your typical carved pumpkins but 10 years ago, Vella began using a technique is borrowed from Renaissance mural painters.

“You take a drawing, painting, or photo, 8 X 11, tape it to the pumpkin, take a sharp pin, and outline the image, using a permanent magic marker to connect the pin prinks,” Vella said. They have evoked African masks, Egyptian art, the Devil, Harry Potter, King Kong, Mr. Smith from “The Matrix” and more. “I never thought of myself as artistic, but I am improving each year,” Vella said.

Vella values family time above all else, which includes visiting with his two grandchildren, and family trips to Mendocino, Carmel, and Yosemite. He and his wife have enjoyed much international travel but have cut back a little due to knee and back issues. “I’m optimistic we have a lot of time left to enjoy life as our parents lived into their 90s,” he said.

His youthful interest in the priesthood had more to do with time and place than any specific yearning. Vella said that smart young boys going to Catholic schools in the 1940s and 1950s were singled out by priests to join the seminary life. “I liked the attention and was rather naïve as to what lay ahead for me,” he said.

He attended St. Boniface Elementary School in downtown San Francisco, which was run by Dominican sisters and Franciscan priests. At 14, persuaded by vocational talks presenting service in a compelling light, he agreed to enter the Franciscan seminary in Santa Barbara in 1958 for high school.

He graduated from San Luis Rey College in 1967 with a bachelor’s degree in Scholastic Philosophy. He had completed one year of graduate school in Theology at Old Mission Santa Barbara when he left to face the draft during the Vietnam War. “I was willing to go to prison, but I won a state appeal to secure my Conscientious Objector status,” he said.

‘Too little health care’

Instead of being drafted, Vella worked as a counselor in the Conard House in San Francisco, a 20-bed halfway house for patients with severe psychiatric illness, while studying Education Counseling Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He graduated with a master’s degree and a Ph.D. “It was an incredibly great experience for my psychology training,” he said.

In 1977, after three years working at the University of San Francisco’s Counseling Center, Vella started a predoctoral year at Kaiser San Francisco’s Psychiatry Department, where he received his psychology license. The next year, he was hired as a full-time clinical psychologist doing individual and group psychotherapy and testing.

During his tenure at Kaiser, he supervised psychologists and post-doctoral students, facilitated groups for depression and adult children of alcoholics, did many regional talks on neuropsychological topics such as dementia and memory, and gave public talks for Kaiser Senior Education and organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association.

Vella’s view of the current state of mental care in the United States is that while there are now “many treatments that are scientifically based and actually work, not enough people have anywhere near acceptable access.” Drug addicts should be in treatment, not jail, he added

He believes free public health care, food, work, and health care are a human right.” There’s “too much poverty, too little health care,” he said. “I believe in a universal basic income.”