Early computer nerd – now a regular at future-focused public space with bar – slowly realized he “was in the middle of something big”

Contact her at myrakrieger@sfseniorbeat.com

When Theo Armour was a young boy, he played a lot, but not with the popular toys of the day like Mr. Potato Head, Silly Putty, or Hula Hoop. Even at six or seven, he said, he was doing “technical stuff.”

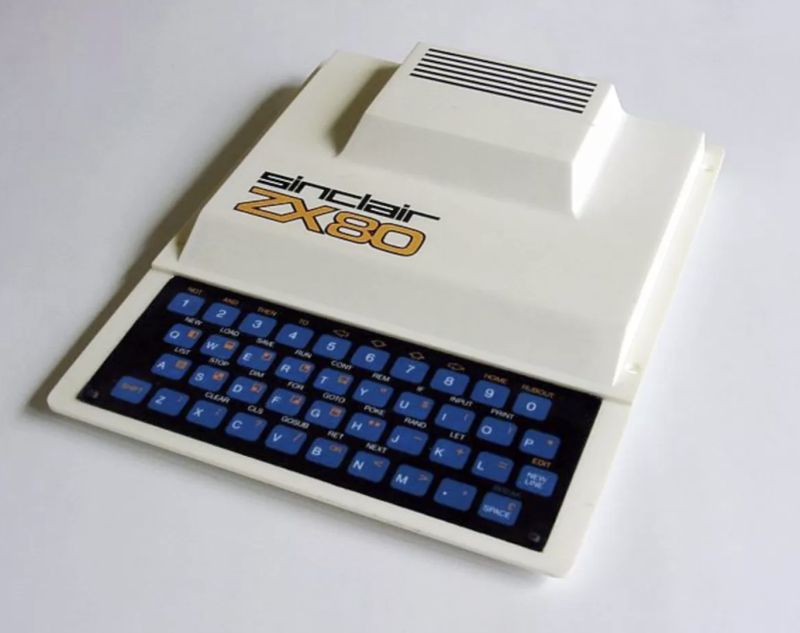

“I was already playing with my calculators, using little baby computers,” he said. “I was just mucking around with this stuff, to see the pleasure in seeing in what I could do.”

He eventually wrote programs in BASIC on a Sinclair computer to produce tiny, three-dimensional structures.

Even though he says, “I don’t know how I got to be who I am today,” it seems he was destined to be involved in the computer revolution in some way. With a start in architecture, he eventually became a pioneer in a leading-edge technology that made mind-numbing design work cost- and time-efficient as well as precision-oriented.

Armour’s early work in 3D modeling and visualization was critical to modern CAD systems and the now widely used AutoCAD, a general drafting and design application with which architects, project managers, engineers, interior designers, graphic designers, city planners, and other professionals prepare technical drawings.

Changing the world

“I have helped change the world. What does this mean, or what it’s worth is beyond me,” he said. “While each change was happening, I slowly realized that I was in the middle of something big. I was not the only one, but each time, I was just one of perhaps a few dozen people getting these things going.”

It was while working for a group of English architects in 1981 on a commission for a mass transit subway in China that he saw how software could expedite what was once grueling and time-consuming work. Up until then, drawings by structural engineers, architects, and draftsmen were a paper-and-pen affair.

AutoCAD, which was launched in 1982 by the Sausalito company Autodesk,” expedited everything,” he said. “With many changes, you usually would go with a razor blade and scratch out the ink. But if you move the columns, it’s too many lines. Another 40 hours working on the same drawing so that three columns can be moved over.”

He became the first dealer of AutoCAD in Asia at a storefront called PC Plus, managing about 20 people selling IBM computers, PCs, and Macs. He subsequently became the first dealer in Asia for AutoCAD and stayed in this role up to 1998.

Most of Armour’s career has been devoted to projects that involve technology, including Artificial Intelligence. He has also been the site designer and webmaster for other designers, artists, curators, and galleries. After leaving Autodesk, he became an angel investor and a technical advisor to some 20 startups. “All of which pretty much failed or had limited good outcomes for me,” he said. “Though some individuals did go on to prosper.”

In the mid-2020s, Armour was invited to events organized by Google to show audiences the capabilities of WebGL, its software interface for rendering interactive 2D and 3D graphics without the use of plug-ins.

Bar for brainiacs

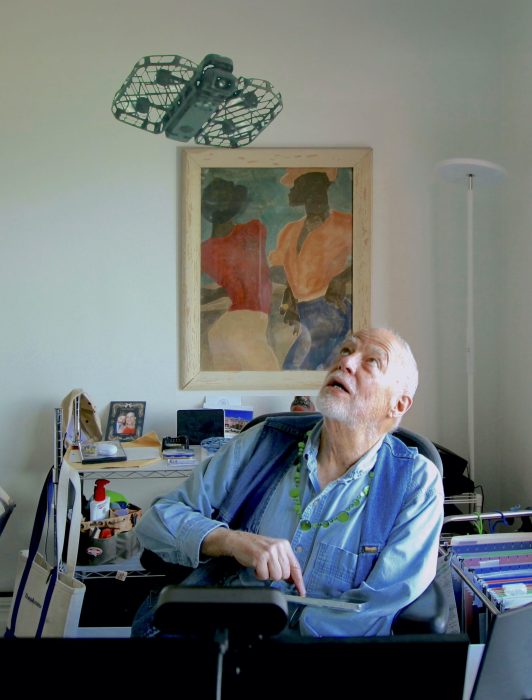

These days, he enjoys flying a drone that’s easy to control with just one hand. He uses it to take pictures and “see things from a vantage point of view that I, as a disabled person, could not otherwise be able to envisage,” he said, such as architectural details like “the capital of a Corinthian column or a window at the top of a building.”

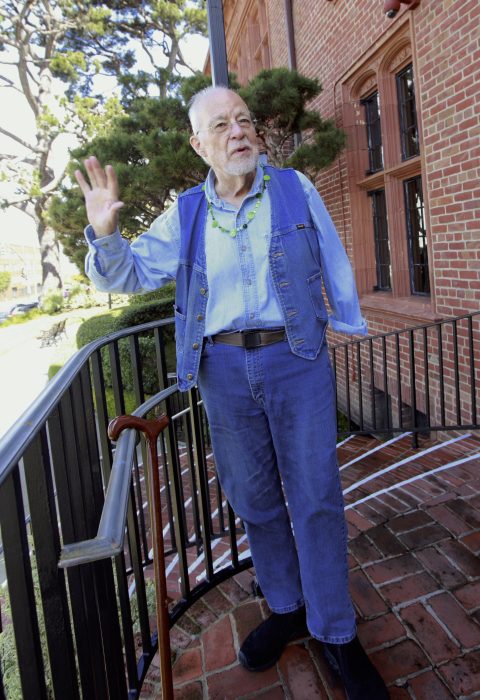

The gregarious retiree is also a regular at several bars within walking distance of his retirement home, the Heritage on the Marina, where he is the “resident techie,” and editor and publisher of the resident directory and 20-page monthly newsletter.

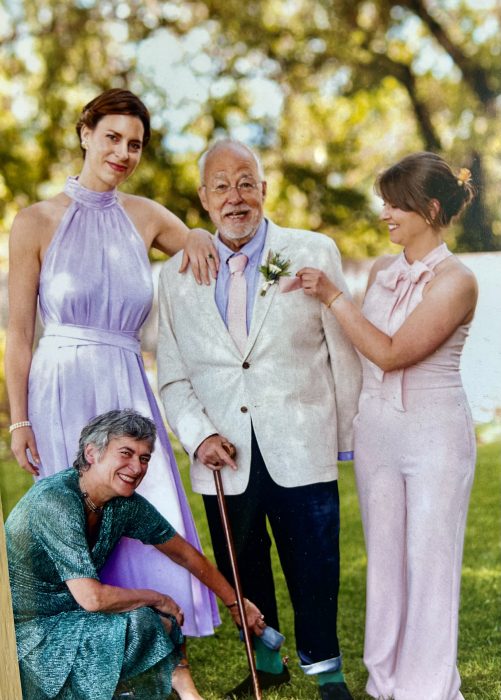

One of those is The Interval at Fort Mason, an artisan bar and space for a community of long-term thinkers and projects supported by the Long Now Foundation, a global nonprofit launched in 1996 by Mother Earth Catalogue co-founder Stewart Brand and esoteric music producer Brian Eno. He recently took one of his three daughters, who was visiting from Amsterdam, there.

Backdrop to the bar is a floor-to-ceiling library of books that might be needed to “restart civilization from scratch” and prototypes for a clock meant to last 10,000 years, now being constructed inside a mountain in West Texas.

Armour enters The Interval on a walker with wheels and easily engages familiars and strangers in conversation. He has managed with a faulty gait and one hand from a terrible accident in college that put him in the hospital for a year.

“I guess you could say that tripping over the parapet of the roof of my dorm and falling four floors could be termed a `misstep’,” he said. “I broke my back, lost my arm, spent a year in the hospital, and still don’t walk well.”

He has a prosthetic device he can attach to the stump of his left arm, but he rarely uses it, he said. “It’s not particularly comfortable and of no great use to me since I’m so well adapted to living with one hand a stump.”

But that’s not kept him from work – or play.

“When you’re disabled and you can’t walk and you’ve got only one hand, there aren’t many sports you can do, right?” he said. “And through the process of elimination, I found that I like swimming anyway; it’s a nice, clean feeling.”

Champion swimmer

Armour, in fact, excelled at swimming. In 1980, he was awarded the Van Audenernaerde Tankard Prize for Best Disabled Swim in the Channel Swimming Association contest. “I swam 19 miles out of 21” across the English Channel. “Almost made it.” In 2006, he came in first place as the fastest disabled swimmer in the annual “Escape from Alcatraz” competition hosted by the Dolphin Swimming and Boating Club on the city’s northern waterfront. Compared to the English Channel swim, he called this event “a piece of cake.”

An extra bonus: “You meet good people, too, at the Dolphin Club,” he said.

Since the 1970s, Armour has served on several boards, including the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2001 to 2011; the Sports Association for the Physically Handicapped in Hong Kong, 1982 to ’87; Websight Design in San Francisco, 2016 to 2024; and gbXML.org, 2016 to present.

Now 78, Armour was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and grew up in a blended family: two sisters and six stepsisters and brothers. His father was a career diplomat and Assistant Chief of Protocol for the United States State Department. His mother was a homemaker.

After attending several schools in the United States, including Syracuse University, Armour traveled abroad to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, England.

Right out of school with a bachelor’s degree in 1975, he got on board with a tenant cooperative in South London, where he helped launch a large-scale community project renovating and rehabbing 80 old houses in South London’s Clapham neighborhood, where plight and poverty prevailed: toilets outdoors, stairs broken, brick walls crumbling, classrooms failing apart, etc.

“With three partners, we did all the designing – a whole row of terraced houses, including one in which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had lived for a while.”

As the South London project wrapped, Armour took a sabbatical during which he met Isabelle Ferté, whom he married in 1981. They had three daughters now in their 30s. Though the marriage dissolved, he said he is great friends with his wife.

The year they married, they left for China, mainly because Armour was curious about socialism.

China calls

“I wanted to be part of making something good happen, and in many ways, I did. But not the revolution I thought it was going to be. Not the socialist revolution, but the revolution in getting China to go from a pre-industrial economy to a fully-fledged industrial economy.”

Armour arrived as Cultural Revolution policies were being replaced by reforms intended to modernize the economy and open it up to foreign investment. “I became a capitalist,” he said.

Within three days, he had landed a job, doubled his English salary working for Yorke, Rosenberg Mardall, the firm designing a new subway line going out of the harbor from Hong Kong to Kowloon.

Yet, it was when he began working for Autodesk, he said, that “my life was changed forever. I was invited to China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Korea to demo to users and CEOs. I showed them that with AutoCAD, you can design a factory on your computer, and when the factory is built, you can design the products the factory manufactures.”

Hundreds, sometimes thousands of people would come to see his seminars, pick his brains and challenge him, he said. “My nickname in the region was `Dr. ACAD.’

“By 2000, almost every architect and engineer in the world was drawing on a computer screen. And most of them were using AutoCAD Release 14, a program I helped design, build, and ship.”

The latest version of AutoCAD, 25.1, was released in March.

Playing a part in the development of a software now used by designers the world over was “all encompassing,” he said. “There are moments of joy, moments of despair, moments of fear, moments of elation.”

And he hasn’t given up on being part of something big again. “I am lucky. I care. I dream,” he said. “What is next? I don’t know. But I am ready.”

Colin Campbell contributed to this report.

Theo

And as Robert Frost said, "And miles to go before I sleep. And miles to go before I sleep."