Chronicling seniors upended author John Leland’s notion of happiness in later life

After I read John Leland’s new book, “Happiness is a Choice You Make,” I went out and bought copies for my children. I don’t want it to take them as long to learn what he did: that the years after middle age are just another chapter in a long life. What happens to an aging body is not tragic, but it might mean some adjustments.

After I read John Leland’s new book, “Happiness is a Choice You Make,” I went out and bought copies for my children. I don’t want it to take them as long to learn what he did: that the years after middle age are just another chapter in a long life. What happens to an aging body is not tragic, but it might mean some adjustments.

Most seniors, as Leland discovered, don’t focus on their infirmities. We’re too busy enjoying the pleasures of the day and what we’re doing right now.

An award-winning journalist with the New York Times, Leland in 2015 began an assignment that was to change his life. His series “85 & Up” looked at what it was like to be elderly through the lives of six New York City residents. What he experienced upended his own notion of aging, along with his relationship with his mother and his way of being in the world. And it evolved into his latest book.

When Leland began the assignment, his own life was presenting challenges, leading him to question the meaning of life and relationships. His mother had moved to senior housing near him after his father died, but he didn’t visit as much as he thought he should have. The few dinners they did share were uncomfortable for both of them. “My role as caregiver wasn’t one that either of us asked for,” he wrote.

Before even starting the assignment, Leland was certain it would be a story about loss, loneliness, deterioration of mind, body and quality of life. Instead he found a new way to look at aging: Debilities don’t have to define people; they are just extra things to deal with. Leland now believes we’d do ourselves a big favor to embrace – not fear – the mixed bag the years have to offer, however severe the losses.

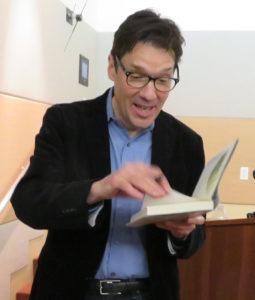

John Leland is a funny, engaging and enthusiastic storyteller. I spoke with him before his April appearance at the San Francisco Institute on Aging.

How did you choose the people for your Times’ series?

I was looking for ordinary people. I asked for referrals from senior centers and nursing homes, the YMCA and the JCC (Jewish Community Center), law firms addressing senior issues, home-care agencies and personal web pages. I selected Fred, Ping John, Helen, Ruth and Jonas because they represented a diversity of race, class, gender, sexual orientation and living situation. All had lost something: mobility, vision, hearing, spouses, children, peers, memory. But few had lost everything. It should be noted that Jonas Mekas, 93, is an accomplished filmmaker and writer, and definitely stretches the definition of “ordinary.”

How often did you visit them?

I visited them once or twice a month for a year. Initially I was afraid that my visits would tire them out. But in the end, we had become family and that wasn’t a concern.

How did being your mother’s caregiver influence this assignment?

When she moved to Lower Manhattan, neither of us was well equipped for the stage of life we had stumbled into together: She, at 86, without an idea of where to find meaning, and me without an idea of how to help. But there we were.

It was a huge benefit to me to see people who weren’t my mother navigating this stage. When I was with them, all I had to do was listen and accept them as they were. I didn’t have to fix them. When I applied that lesson to being with my mother, when I began listening to her rather than trying to fix her, I found we both enjoyed our time together.

What characteristics do people who navigate aging well possess?

When I started the assignment, I thought I would be showing the pains and hardships of age. What else, I reasoned, was old age made of?

What I found was that the elders I spent time with didn’t focus on these hardships. It didn’t mean they didn’t deal with loss and disability, only that they did not define themselves by it. Like all of us, they got up each morning with wants and needs, no less so because their knees hurt or they couldn’t do the crossword puzzle like they used to.

Small pleasures may only seem paltry because we haven’t lived long enough to see their value, or survived enough losses to know how surmountable most losses are. … Whether the lens is a telescope or a microscope, the wonder lies always in the eyes of the beholder.

Old age wasn’t something that hit them one day when they weren’t careful. It also wasn’t a problem to be fixed. It was a stage of life like any other, one in which they were still making decisions about how they wanted to live, still learning about themselves and the world. If you think of life as an improvisation in response to the stream of events coming at you – that is, a response to the world as it is – then old age is another chapter in a long-running story. The events are different, but they’re always different, and always some seem too much to bear.

Tell us more about Ruth and the issue of interdependence

Part of Ruth’s dread of living too long was that she might become a burden to her children. It’s interesting because she would never have considered her children a burden to her when they were young; nor did she consider it a burden to care for her husband and her sister through their illnesses. You know, it’s harder to accept help than to give it.

Ruth clung to her independence, not wanting to use a walker or have help for her finances. At the same time, she was grateful when her daughter took her to her doctors’ appointments or when any of her four children visited. At her children’s insistence, when she was 92, she moved to an assisted living facility near her daughters.

Ruth’s conversation over the year tended to fall along three lines. On the one hand, she talked about things happening to her, especially as she got older: leaving friends and activities she used to enjoy, loss of ability to set her own schedule. The worst part was that she knew these losses presaged more substantial losses to come, a last chapter characterized by ever-diminishing autonomy and control.

She talked often about the past. Gradually I noticed that when she shared past memories, it was to talk about the things she did for herself: raising her four children, attending square dance classes with her husband, caring for her mother or sister. When she remembered setbacks from the past, she wanted me to know how she overcame them.

Her other line of conversation focused on the things she still could do for herself: mastering new skills on the computer, the books she was reading, joining a protest outside her new building, even small things like ironing her clothes or balancing her checkbook.

Over the year, Ruth began to reveal a third line of conversation, involving the support network of her family. When her children were younger, the more Ruth did for them, the fuller her life was. Now she was discovering that the more her children did for her, the more satisfaction they got out of it. Instead of insisting on independence, Ruth was trying to navigate being interdependent, which meant accepting help with gratitude. It gave her a sense of purpose that often eluded her in the assisted living facility, where all she really had to do was show up for meals.

We all need to learn how to be interdependent in old age. The idea that we have to be self-reliant and stand up on our own two feet is over-rated. Let people do favors for you, accept help. It’s given with love. Ruth’s daughters (like Leland and like me when I took care of my mother) saw her every ailment as an obstacle to overcome, a tragedy to be averted. They didn’t realize what a full life their mother lived. While they focused on day-to-day changes, which were almost always for the worse, Ruth looked more in the continuum: Her history of overcoming past challenges gave her the confidence that she probably would overcome the current obstacle.

What societal changes do you think could make aging easier?

I think there should be more opportunities for cross-generational activities, for us to get together in a way that benefits everyone. Old people are an asset, a repository of wisdom. Let’s think of them as a resource.

Your book has only a handful of quotes from gerontology experts. Why is that?

The seniors who are living aging are the experts, not the experts who write about it.

How have you changed your life since writing the book?

I’ve changed in several ways. For one, I’ve become more patient; I’m almost able to declare victory over my curmudgeons. Like meditation, which I’m just beginning to study, aging teaches the importance of putting a space between stimuli and your reaction to the stimuli.

So often we measure the day by what we do with it … and overlook what is truly miraculous, which is the arrival of another day. On the days when the elders’ wisdom sinks in, I sleep peacefully – and help a stranger, call an old friend or tell my partner I love her, write in joy rather than in struggle. Gratitude, purpose, camaraderie, love, family, usefulness, art, pleasure – all these are within my grasp, requiring of me only that I receive them. These days I am kinder, more patient, more productive, less anxious, possibly closer to being the person I always should have been. Whatever aches I had, or fears, are still with me, but they’re now supporting instruments in my soundtrack not the music itself.

I learned that the old don’t have time for delusions, including the delusion that they have time. They’re too busy living like there’s no tomorrow. For any of us, there might not be. I came to realize with John (one of the elders) that accepting death – wishing for it, even – didn’t devalue the days he had left, but made each count more because they were so few. That’s why talking about wanting to die could cheer him up. Death gives everything its value.

Theirs was a lesson in giving up the myth of control. If you believe you are in control of your life, steering it in a course of your own choosing, then old age is an affront, because it is a destination you didn’t choose. But if you think of life instead as an improvisation in response to the stream of events coming at you – that is, a response to the world as it is – then old age is more another chapter in a long-running story.