Parkinson’s patients gain strength in darkened boxing gyms as well as light, airy ballet studios

Rebecca Lum never thought she’d find herself in a boxing gym. But there she was in a dark room, one wall plastered with pictures of “mean-looking” boxers and heavy metal as background music.

But it’s where she first found relief from the stiffness of Parkinson’s Disease. After years searching for a diagnosis for the wild tremors she began experiencing in her right hand and foot, she found a doctor who recommended she give it a try.

“I loved boxing at the beginning,” said Lum. “It’s such a good workout and I felt so energized afterwards.”

Rock Steady Boxing, now available in 300 gyms nationwide, was founded in 2006 by an Indiana prosecutor who developed Parkinson’s and designed by his friend, a Golden Gloves Boxer. It was the first program of its kind in the country to specifically address Parkinson’s Disease.

But it took Lum seven years to discover it. She had consulted several neurologists, all of whom said they didn’t know what was wrong with her but it definitely wasn’t Parkinson’s. It wasn’t until 2015 that a neurologist identified it as the source of her problems. “I mostly felt relief, because now I could pursue treatment,” she said.

For many years, exercise was thought to be of no value for people with Parkinson’s, a progressive deterioration of motor skills, gait, balance, speech and sensory function. Visible symptoms include tremors, stooped posture and a shuffling gait. In fact, it was thought exercise might injure patients or aggravate the condition.

In the 2000s, however, physical therapists began to incorporate into their practices new research on body-brain connections revealing the plasticity of the brain. In 2018, a Mayo Clinic review of research found aerobic exercise to be particularly useful in slowing disease progression, even recommending it as routine advice to patients.

Big movements to the rescue

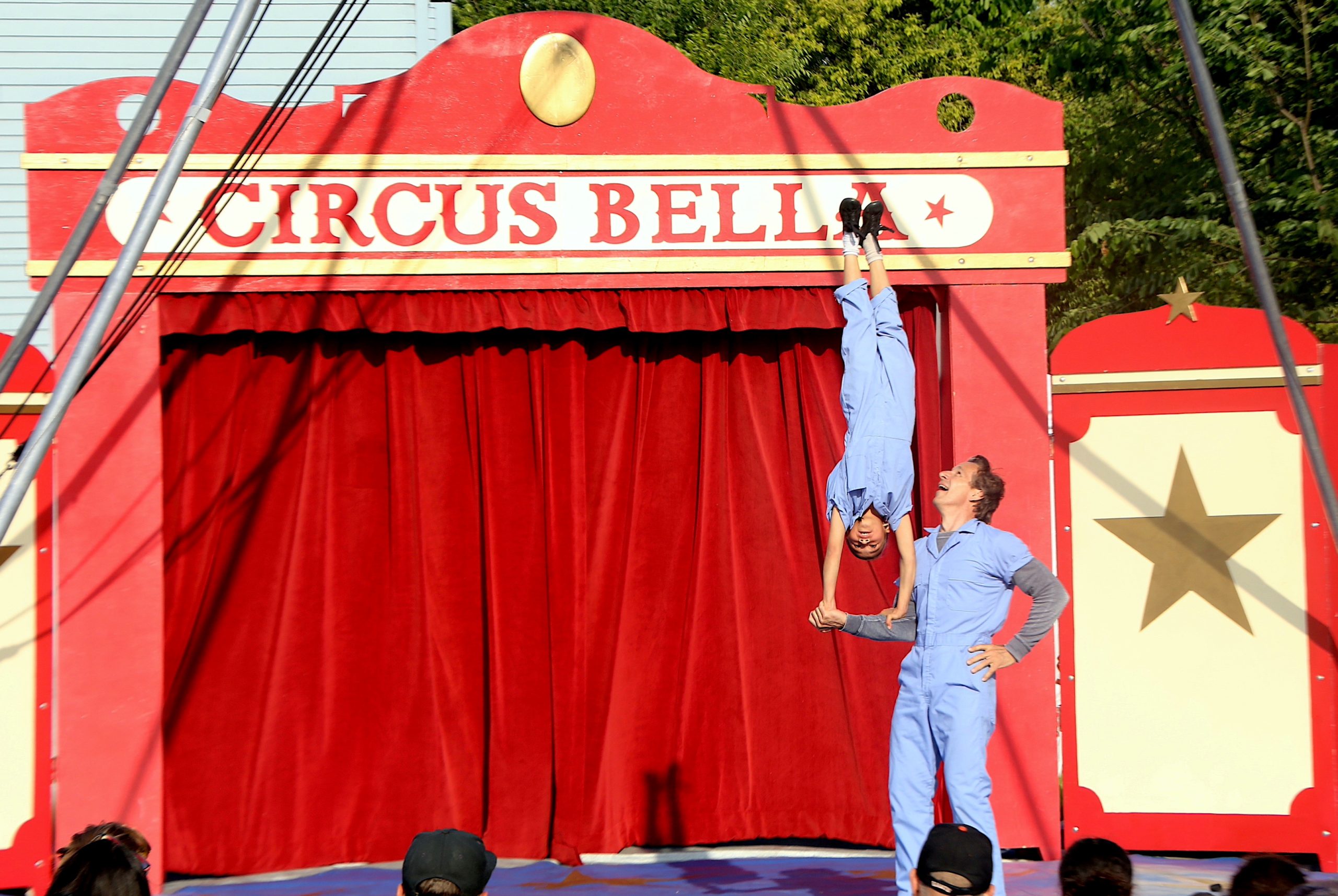

Boxing and dance, especially ballet, have in the past several years been gaining a lot of adherents among people with Parkinson’s. Both deal with balance, flexibility, coordination, strength and mental agility.

For instance, stepping with high knees while swinging the arms widely on opposite sides of the body counteracts the crunched steps often seen in people with Parkinson’s. Big gestures in general help deter shuffling, as well as constricted posture and cramped writing, or micrografia.

Deep stretching encourages flexibility and deep breathing, expanding the lungs.Trunk rotation counters stiffness in the neck and torso and is also good for the brain. Extension of the arms is helpful, whether in balletic movements or punching a bag.

Combinations of movements are mentally as well physically beneficial: Remembering moves in the correct sequence builds cognitive skills, whether dance steps or Muhammed Ali’s fancy footwork.

At Rock Steady, Lum did boxing drills with punching bags and medicine balls. The gym is open to anyone to come in and train, she said, “and you hear a lot of ‘Huhs!’ and ‘Hai-yas!’ from the regulars.”

But she admits the atmosphere took some getting used to. “It’s not a place I’d want to hang around all the time,” she said.

So, when she came upon a flyer at the gym for a ballet class for people with Parkinson’s at the San Francisco School of Ballet, Lum signed up immediately.

Dance for PD®, founded in 2001 in New York, is specialized dance for people with Parkinson’s, their families, friends and care partners. It has affiliates in more than 300 communities in 25 countries around the world.

See the KPIX video on Parkinson’s and ballet.

Kaiser Permanente sponsors classes at the San Francisco School of Ballet. Director Patrick Armand, whose mother had Parkinson’s, set up the program. Cecilia Beam, retired after 40 years as a ballet instructor, is the teacher. She worked with the Mark Morris Dance Group in Brooklyn and with Kaiser physical therapists to develop the class.

Both boxing andf ballet have helped Lum, “but ballet!,” she said, “if they offered it every day, I’d go every day. Ballet suits my temperament better; it takes me into such a beautiful world.”

The studio is so light and airy, she said. “When the music starts, you just want to go flying across the room!”

The class starts with big, exaggerated gestures, such as bowing to the people in a balcony, or picking flowers then tossing them away. Then they do chair exercises to warm up before going on to choreographed movements.

Ballet doesn’t come as easy for Richard Wortman, 73, who also takes boxing classes. “I’m always glad I’ve made it to the class,” he said, “but I think I take it too seriously. I really want to get it right. I need to let myself have more fun while I’m doing it.”

What he most enjoys about boxing is putting on the gloves and punching the bag. “It’s a great workout and you can just about convince yourself that you could really become a boxer if you put your mind to it!”

What he likes about both classes is being part of a community. “I really look forward to seeing these people every week.”

It’s the community

Lum agrees that if there is anything good about having Parkinson’s, it’s the collegiality of people facing the same challenges. “It’s a real plus for me to be able to get to know the others better and to share resources and techniques for managing Parkinson’s,” she said. “You see how wonderful people can be, how supportive and helpful.”

After two years of both boxing and ballet classes, Lum reports, “My balance is better. I can count on two to three hours a day when I feel pretty normal. Then, you always have to wonder is a new symptom Parkinson’s, or is it a normal age-related problem? Or just anxiety.”

The Parkinson’s Disease Foundation estimates there are more than 1 million people in the United States with Parkinson’s. More than 60,000 people are diagnosed each year. But published medical research has shown that intense exercise can reduce, reverse and delay Parkinson’s symptoms.

“It’s only when you look back do you realize how much you’ve changed,” said Lum. “A woman in my ballet class was in a wheelchair when she started taking ballet two years ago, and she doesn’t need the wheelchair anymore.

“So we won’t get cured but the quality of our lives can improve through exercise.”