From the Kennedy assassination to New Age practices to medical issues to San Francisco and the Coast, Lithuanian emigree covered it all

Rasa Gustaitis was among 900 other displaced persons who arrived in America in September 1947 on the SS Ernie Pyle. With her own long career in journalism, it now appears serendipitous that she entered the country on a ship named for a Pulitzer-winning war correspondent.

Gustaitis touched all the bases in her journalism career —she worked for major newspapers, wrote five book and taught at two universities. And she has another book about to be published.

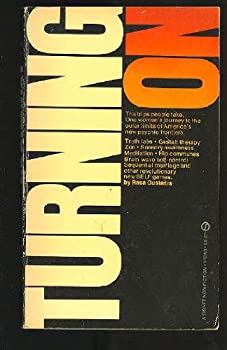

From 1960 on, Gustaitis wrote or edited for newspapers including the Washington Post and the New York Herald Tribune as well as the Pacific News Service in San Francisco. She taught journalism at the University California-Berkeley and San Francisco State University. And, she authored five books, including “Turning On.” In this personal romp through the New Age, she explores the iconic Big Sur havens – the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center and the Esalen Institute and its outdoor baths – and experiences new bodywork and healing practices, such as Rolfing.

Her last paid job was as Editor of California Coast and Ocean, a quarterly magazine published by the Coastal Conservancy Association. She led the nonprofit’s editorial staff from 1986 until it closed in 2009.

Gustaitis was born on May 19, 1934 in Kaunas, Lithuania; she is 86 years old. She describes the first six years of her life as “peaceful and comfortable.” But in 1940, the Russians invaded and occupied her country, deporting hundreds of thousands to Siberia.

Russian invasions and a tragic loss

Her father, Antanas, was an aeronautical engineer and brigadier general, chief of the Lithuanian Air Force. Much to the chagrin and forewarning of colleagues who had fled, he stayed behind. Eventually, he tried to cross into Germany to get visas for the whole family, planning to relocate them all safely in Argentina, where he had job offers. But he was caught at the border. The family never saw him again.

In 1968 after a tireless search, the family learned he had been taken to a prison in Moscow and executed in 1941.

Now independent, Lithuania suffered three invasions between 1940 and 1944: first the Russians, then the Nazis, and then again the Russians. Gustaitis sees both as tyrants. “The difference is that the Nazis were systematic in their terror,” she said.

Gustaitis talks about this chapter in her life in “Flight,” her upcoming memoir. It’s a familial tale that takes the reader into Eastern European history all the way back to the 19th Century, as a daughter searches for her father, who disappeared in a Moscow prison during World War II.

Sailing to America under aunt’s auspices

In 1947, after several relocations, a 12-year-old Gustaitis, her two sisters, mother and grandmother sailed to America. It was one of many moments in her life that she felt she had guardian angels looking after her. The family was sponsored into the U.S. by an aunt in Brooklyn. A cleaner of offices on Wall Street, she pressed hard for the family’s entry, and guaranteed they wouldn’t need public assistance.

At first, it was a hardscrabble life, the family of five living in her aunt’s tiny apartment. Her mother worked as a nurse and her older sister got work as an attendant at a mental hospital.

As soon as her mother earned enough, they moved into a basement apartment. Gustaitis was enrolled in public school but being tagged as a “displaced person” helped her win a full scholarship for her senior years to an elite girls’ boarding school in Wellsley, Ma. In 1956, she earned a bachelors’ degree in Government at Oberlin College.

After a five-month backpacking sojourn throughout Europe, she returned to the States, ready for work. Having been a writer of stories even as a child, she chose journalism

Curiosity is her driving force

“What drives me in my work then and now is curiosity,” she said. “Something catches my attention; I pursue it to learn more and understand. If it is something I care about, I plunge in.”

In 1960, she got her masters’ degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. long before such degrees were common among journalists. “This is where all the work was entirely `hands-on’; you were out in the field getting and writing stories,” she said.

As soon as she graduated, she got a job reporting for the Washington Post, covering city news. And in the nation’s capital, that could be of local interest – a slum landlord in cahoots with city officials; national interest – the Kennedy assassination, the March on Washington or international – following Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selasie around town after he visited the White House.

After five years with the Post, Gustaitis joined the New York Herald Tribune. It may have been the underdog to the New York Times, but it was filled with “good writers, and I learned a lot,” she said. As a general assignment reporter, for both the Tribune and the Post, she covered a “grab-bag” of stories, she said.

The Tribune folded in bankruptcy in 1967, launching Gustaitis on the next phase of her writing career – as a freelancer, author and Professional Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.

Stories to be proud of

She is especially proud of an article she wrote for New York Magazine. “The Fight for Beth Liuni” describes how ethnicity almost scuttled a wanted adoption. When an Italian couple who had fostered the fair-haired, blue-eyed Beth from birth tried to adopt her, the ethnic difference was challenged by adoption authorities. It ended up in court: The ruling supported the adoption.

Freed in a way from daily journalism, Gustaitis turned to writing books, which gave her “an opportunity for deeper exploration,” she said. “Turning On” was published in 1970. She also worked with co-author Ernlé Young on “A Time to be Born, A Time to Die: Conflicts and Ethics in an Intensive Care Nursery.” Published in 1986, it was named “Book of the Year” by The American Journal of Nursing and earned a Meritorious Achievement award from the Northern California Professional Journalism Society.

In 1976, Gustaitis returned to full-time work – at the Pacific News Service, a nonprofit focused on youth and the marginal in society. But she had what she calls one of her most influential years in 1983-84, after leaving the news service and before joining California Coast and Ocean.

In a competitive process, the paid fellowship at Stanford took in a handful of working journalists each academic year. The goal was to give them a breather from the daily news grind, to pursue any paths of education or exploration they chose.

In seeking the 1983-84 fellowship, she wrote: “I was voracious, as journalists tend to be, I suppose, and also scattered because the nature of our work propels us from one theme to another, hitting high spots, moving on before we can fully explore anything.”

When her fellowship was done, she went to work for California Coast and Ocean. Along the way, she married a professor of sculpture at the California College of Arts & Crafts in Oakland. He had a daughter from his first marriage; together they had another daughter. Today she lives in Noe Valley; her daughter’s family – husband and child – live in a cottage behind her home.

Family and martial arts keep her grounded

Family has been a mainstay since she retired in 2009. But she misses seeing her stepdaughter and family, who live in Alaska and northern California. Writing and martial arts also keep her healthy, productive and curious.

“For me, the study and practice of Aikido and T’ai Chi Chuan has had a direct bearing on my work, my enjoyment of life, the way I move through the world; the way I relate to people.”

She still follows the news. Her parting words for consumers: (1) Question everything, (2) Distrust authority, and (3) Look for different perspectives.

As for today’s journalism, she said, it has become more hazardous.

“News people have been targeted and killed in many countries in recent years. Excellent reporters are doing courageous work in media that did not exist when I was a daily newspaper reporter, as well as at such print media as still survive. Such work is more important than ever.”

You may contact the author at myrakrieger@sfseniorbeat.com.