Senior Beat examines in-home caregiving crisis: High costs leave most middle-income seniors in the lurch; worker supply lags demand

Because of its importance – and continuing concern – Senior Beat has decided to re-publish in whole this series produced last May by staff writers Mary Hunt and Judy Goddess.

Their stories look at a complex health-care system that leaves most middle-income seniors on their own for in-home help affordable only for the wealthy and which the impoverished get through MediCal. It depicts a trend that’s only expected to mushroom as the population ages: that the need for in-home support will far outstrip the caregivers willing to accept typically low pay with few benefits. The result is that the burden of in-home care largely falls on family members – of all income levels.

As of 2020, there were 2.3 million home care workers in the United States, according to April Verrett, president of SEIU Local 2015 in California, the nation’s largest long-term-care union. And if we are to meet the needs of our aging population, she wrote in TIME magazine, we’ll need another 1.2 million by 2028.

THE STORIES:

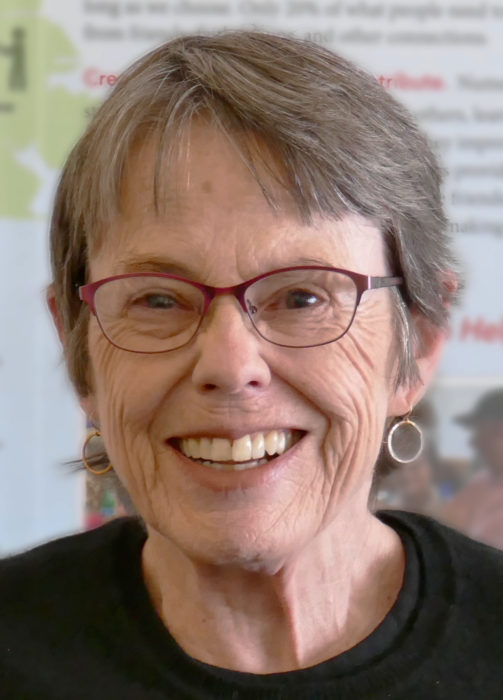

High costs and dearth of financial assistance programs for middle-income seniors leave them in the lurch when help at home is needed. The Rev. Eileen Kinney is one of the many Americans, those of middle-income, for whom costly in-home care is unaffordable. She began having trouble with basic tasks like cleaning and cooking when her neuropathy worsened. But not being wealthy enough to hire care, nor poor, which would have qualified for in-home care through Medi-Cal, she had nowhere to turn – until she was able to get into one of the rare programs that offer financial help for seniors in the middle-income gap.

‘I’m too young to need a walker!’ A fall and fracture jolt an independent life in a comfy Stonestown apartment. Mary Hunt didn’t think of herself as old at the age of 76. Even when she broke her wrist in a fall, she didn’t see the need to hire a caregiver. She lived alone but had friends around and a sister in Daly City. Her daughter lives in Georgia. Having some stranger come in felt like an intrusion.

Tending to aging seniors in their homes a necessary and noble but undervalued occupation – rewarding but challenging, emotionally and physically. Debbie Gilli had always loved being around her grandmother and her in-laws. She simply liked older people. It wasn’t much of a stretch to become a caregiver. Anna Kivalu likes the look into other lived worlds she gets when helping clients. Lourdes Dobarganes gets clients to salsa dance with her to strengthen their balance and keep them moving. She’s also been known to have them hug trees for a positive energy experience. They have few complaints about their work, but would like to make more money and have benefits like sick leave or workers compensation. Those obstacles are barriers to the supply of caregivers keeping up with the demand for their services.

Family members make up majority of in-home caregivers due to help’s high cost, taking on all-consuming, sometimes overwhelming role. The high cost of in-home caregiving has led many families to take on the burden themselves. In fact, the vast majority of caregivers serving Medi-Cal clients in San Francisco – hired through the city’s In-Home Supportive Services program – are family members. While most become members of the caregivers union and make slightly more than minimum wage, it is still an all-consuming, physically exhausting and sometimes maddening job.

Neighborhood and ‘village’ networks provide mutual support for seniors as aging makes daily tasks more difficult. Within eight years, a third of San Franciscans will be 60 or older, and according to various studies about a third will live alone. In 2020, that would have been about 54,000 seniors. The ones who have no family, or none that live nearby, are turning to neighbors to form support networks for help with everyday tasks they’re having trouble with – getting to a doctor’s appointment, shopping for groceries, changing a lightbulb –temporarily or long term. Some of these neighborhood networks are informal; others involve low-cost memberships that offer support as well as activities.