No more hugs since Covid, but caregiver to chronically ill compensates with art projects, interesting activities, and for himself, a filmmaking sideline

The last 20 of Stan Stone’s nearly 70 years have been devoted to the lives of the chronically ill and dying. It’s a job that can present more than a few heart wrenches. Luckily, Stone is not only caring but upbeat. He’s got a sense of humor. He’s good-natured.

If there’s anything that bothers him, it’s some of the changes wrought by Covid. “I’ve been a hugger for as long as I can remember,” he said. “Touch has always been so important, and now there feels like there is too much self-imposed distance between me and the world”.

So, his hugs these days take the form of the entertainment, outings and activities he organizes to brighten the days of the 32 people living with HIV at Catholic Charities Peter Claver Community. In another sense, they can be felt in the sometimes quirky, sometimes poignant short films he produces as a longtime member of barewitness films, an award-winning improv collective, many of them available on YouTube.

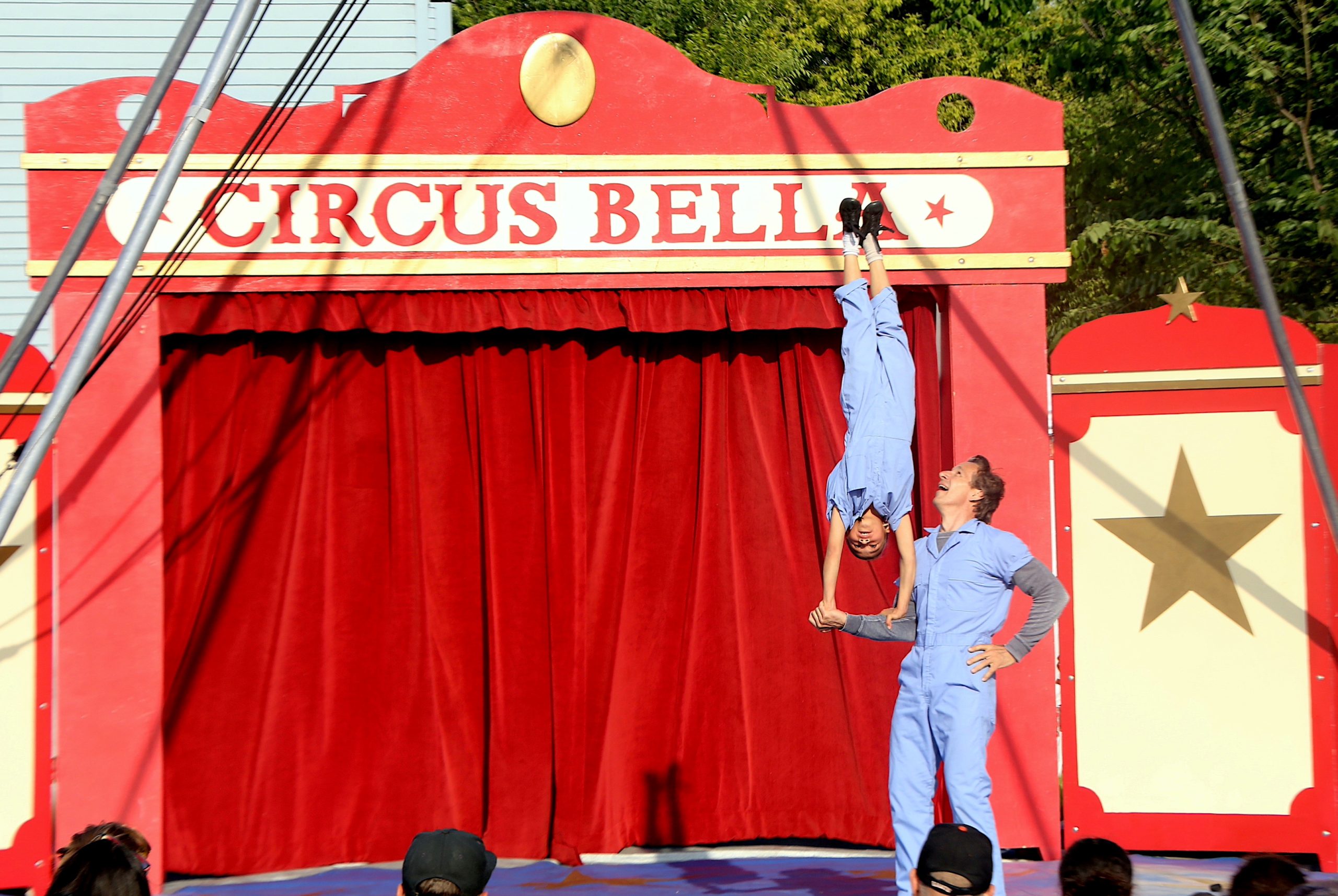

As activities coordinator at Peter Claver, he innovates art projects, light exercises, movies, bingo, and outings to museums, Stow Lake, downtown plays and live entertainment. He recently brought in an opera singer. Using the company van, he has taken groups down to Santa Cruz.

The work of a helping hand to the dying and chronically ill can be enlightening, at times unexpectedly funny, but also emotionally exhausting. “Don’t sweat the small stuff,” he says, because “everything changes in a minute.”

He recalls getting a patient ready to take to his doctor. “He was jokingly conversational and appeared to be on track with me. I excused myself for a few moments to call a cab and collect my things. I returned to his room within five minutes. His head was leaning backward, tipped over his wheelchair. I thought he was asleep; I took his pulse…he was gone.”

Creative outlet

Stone counters the melancholy of such scenes by tending his own life balance. He exercises for about 30 minutes every day and swims a few times a week. When football season arrives, he’s well situated in front of the television. He nurtures his creative juices with sketching, artwork, writing short stories and poems.

On a windy Thursday afternoon in a crowded cafe, the sounds of the Beatles’ “Let It Be,” drifting in from a passing auto, Stone dips into his backpack and hands over his poetry book, “Unlikely Saviors.” It’s a gift, he says.

In addition to writing poetry, he conceives ideas for short films, writes the scripts, directs and sometimes acts in them. In “Buddy,” he stars as a man taken prisoner by his “smart” home. It won 2018’s Best Director award from The 48 Hour Film Project, a sort of flash mob of weekend filmmaking. Like “Buddy,” his most recent film showcases a sense of irony. In “Hanging Chad,” members of a once popular TV ensemble `hoping for a reunion episode ponder whether the star, Chad, will sign on. Stone, as Chad, wraps up with his decision.

That’s one way he shakes off the harder parts of his work, he said: “Get away from the introverted me and into the extroverted me.”

Still, he doesn’t avoid emotional subjects. In “Gone,” a woman whose husband has died finds that remembering him is sometimes too much to bear. In “Johnny & Scrap,” he acts both parts of a romance between two southerners. The show, written in celebration of his mother, who died in 2014, was staged at the Studio Grand in Oakland in 2016.

A yen to serve

Stone turned to the social services sector after college and positions in graphic art, package design and print advertising in Philadelphia, New York and San Francisco, He wanted a job that was more interpersonal, one of service. He first became a certified massage therapist, building a loyal client base for about 10 years. “It was as therapeutic for me as it was for my customers,” he said.

The need for health benefits, a steady income and regular hours led him to a job as activities coordinator at Continuum Health Care in the Tenderloin, supporting people with HIV, addiction and mental health issues. “I loved this job. I learned a lot about people living with addiction.” He also worked at Maitri, a hospice that supports people living with HIV, before joining the Peter Claver Community.

In his childhood, Stone wanted to be an art teacher. In some ways, he has achieved this through his work.

At Maitri, where art supplies were available, he encouraged residents to discover their hidden talents. He reached out to community partners to introduce poetry, journal writing, storytelling, and meditation. He also headed up volunteer teams that helped in many capacities, including sitting at the bedside of the dying.

Michael Pullis, a 13-year resident of the Peter Claver Community, said, “Stan is the best. He helped me get into my own art in ways I didn’t even know I had; I made sculpture out of clay and used oil paints for the first time.”

A loving family

A few years ago, a local art gallery made space for the work of eight residents: collage, sculpture, drawings, oil and ceramic paintings. Stone framed and staged them all for a one-day event. “All these emerging artists sold at least one piece in their collection,” he said, “and the monies went straight back to them.”

Stone is his family name, but it didn’t come from family. It came from the Alabama plantation boss who enslaved his ancestors, according to research by his brother.

Although there were times when Stan Stone was growing up that the heat got shut off because the bill wasn’t paid or the local grocer ran a tab so the family could eat, he and his four siblings lived a middle-class life. His mother was a homemaker, his father a lifetime U.S. postal worker. He still talks to his father, now 96, once a week and visits him in his hometown of Philadelphia twice a year.

It’s with a wide grin that he describes an exceptionally loving and supportive family. In his early 20s, when he struggled with his sexual identity, they came through.

“I felt so much guilt and shame. I had thoughts of harming myself,” he said. “One day my mother sat me down. She asked me if I was `funny.’ I replied, `Of course, I am. Don’t I make you laugh all the time?’ `You know what I mean,’ she said.”

It didn’t matter to her that he was gay. She said she loved him anyway.

“In an instant, the weight of the world was lifted,” he remembered. “I felt free. “

His father, brothers, sister and cousins all responded the same. “To say coming out saved my life is not an overstatement,” he said. “I was given permission to my authentic self.”

In “Unlikely Saviors,” his book of poems, Stone writes:

“I am the son of a Black man

who embraced me

when I confessed to

loving another man.”

Stone married William Salit in 2017; they have been together for 22 years in their Castro home.