Film by Chinatown native and his son continues to bring historic neighborhood’s political struggles and evolution to life

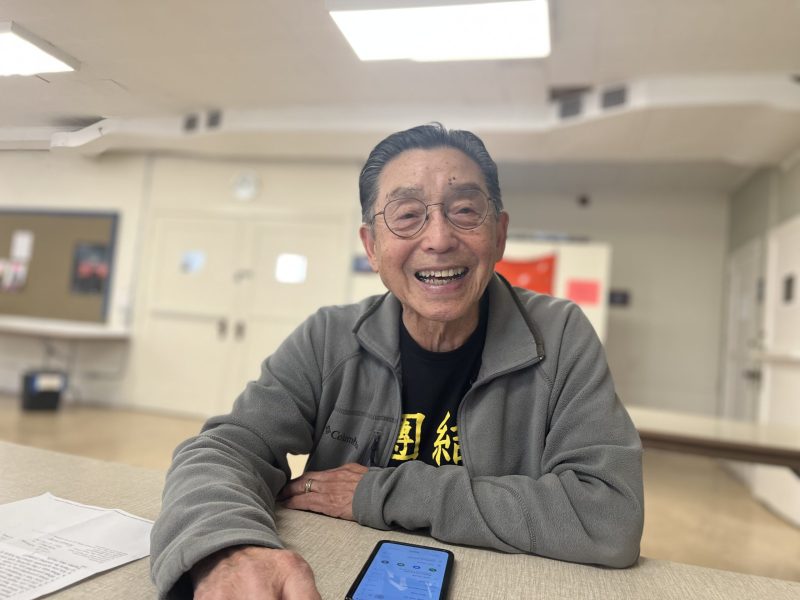

Cleaning out a garage isn’t usually the sort of task that changes one’s life. But when Harry Chuck, then 80, and his son were picking through the junk, they found something that did just that: a dust-covered, lacquered box that contained more than 10,000 feet of exposed film.

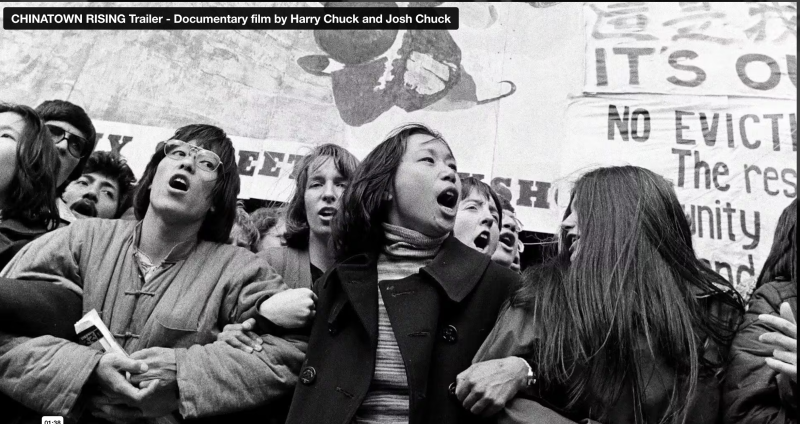

Eight years later those long-forgotten skeins of film tucked away in a rented garage are the heart of a movie that has been shown more than 150 times in cities around the U.S. and on public television’s World Channel. It’s called “Chinatown Rising,” and it tells the story of that San Francisco neighborhood’s struggle for decent housing, ethnic studies, and equality. It’s a story that’s both personal — Chuck shot much of that footage himself – and political.

“If you lose your history, you lose your identity,” said Chuck, now 88. The footage was shot during the tumultuous ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s when Chuck became enamored with film and began to carry a camera everywhere he went – sometimes as an observer, often as a participant. “When I joined a demonstration, I’d just hand the camera to someone else and tell them to keep on filming.”

It would be difficult for an outsider to tell the story of Chinatown with the intimacy that Chuck can, but the filmmaker and his family have deep roots there. Like his parents, he was born and raised in the neighborhood, as was his son, Josh, his partner in making “Chinatown Rising.” Chuck went to school in Chinatown, lived there for decades as an adult, and raised three children there.

Ministering to Chinatown

The film was originally conceived as a graduate thesis: Chuck studied filmmaking at San Francisco State College, now University, in the early 1970s. But that thesis was never completed. “Looking back, I did not have enough wisdom to understand what was happening,” he said.

Years passed. The film stayed in the box. Chuck became an ordained Protestant minister and community worker. He lived in and eventually became the director of Cameron House, which has served the needs of low- and moderate-income Chinese families since 1874.

The Chinatown of his youth – he was born in 1935 – was insular, a place where people kept their heads down. “Because some were illegal, people always said ‘be quiet, don’t make trouble’ or you might get deported,’” Chuck said. Because the population seemed passive, politicians and city officials paid it little mind.

Chuck’s grandparents were poor. To raise money, they forced their daughter, his mother, into servitude, he recounted. He doesn’t know what sort of work she was made to do, but she objected strongly. Eventually, she was rescued by authorities and lived with missionaries in the neighborhood, he said.

It was a neighborhood where people stuck together for survival, what Chuck calls “an affinity neighborhood.” Although it was densely populated, Chinatown was not very large – just 24 square blocks when he was young.

Anti-Asian violence, an issue today, wasn’t a political issue then, although attacks on Chinese and other Asians were not uncommon. “If you crossed Broadway, you’d get chased back.” But the thugs were met and repelled by Chinese if they entered the neighborhood, Chuck said.

Generation without fear

As Chuck’s generation matured and raised their children, the culture of “go along to get along” eroded. “We were the generation that became naturalized citizens, so we didn’t have that fear. We were also picking up on the momentum of the civil rights movement.”

The need for more and better housing was a spark that ignited protests and political activity in the badly overcrowded neighborhood. Many families lived in one-room apartments in dilapidated residential hotels with little or no heat or hot water, and substandard plumbing.

Although the term “NIMBY” hadn’t been coined, plans to build new housing in Chinatown were often opposed for one reason or another, Chuck said. A group of White residents who lived nearby opposed a major housing project, supposedly because it blocked views, although skyscrapers were already springing up in San Francisco.

The object of their ire was what became the 185-unit Mei Lun Yuen apartments. The film recounts a hearing before the San Francisco Planning Commission. Chuck brought a projector to the meeting and proceeded to show a short film clip demonstrating the miserable housing conditions in the neighborhood.

“Since you can’t come to Chinatown and meander through our housing, we thought we would bring our housing to you,” Chuck told the commission.

The audience applauded and the Commission voted to approve the project.

There were defeats as well, notably a years-long fight to preserve the International Hotel on Kearny Street in nearby Manila Town. The struggle culminated in a violent confrontation between demonstrators and sheriff’s deputies there to evict the tenants in August 1977. Chuck was there, and “Chinatown Rising” includes footage by him and local journalists.

Chuck’s family has been part of working-class life in Chinatown since the 19th century. His grandfather immigrated to California from China and worked on the largely Chinese crews building the Union Pacific Railroad. Born in Chinatown, his mother worked as a welder in Bay Area shipyards during World War II. His father was a cook, working for wealthy families on the Peninsula, and later in San Francisco.

Chuck attended Commodore Stockton (now Gordon Lau) Elementary School. Nearly all the students were Chinese, but teachers forbid them from speaking Cantonese. He attended junior high in North Beach, which he called “my introduction to diversity, but few of the teachers looked like me.”

Showing the underbelly

He ventured even farther from the neighborhood, attending George Washington High School in the Outer Richmond, which to a teenager from Chinatown, he said, “seemed like my idea of the suburbs.”

An informal meeting with a visiting administrator from Westminster College in Salt Lake City led to a scholarship and a degree in chemistry. Chuck said he was happy there, but recalls racist harassment by the police.

Returning to the Bay Area, he entered the San Francisco Theological Seminary and was ordained. He spent time in Hong Kong to polish his language skills. When he returned, the neighborhood had changed.

”Protests were everywhere” and increased immigration brought conflict and sometimes violent gang activity. He bought an 8mm camera and began to film activity on the streets. “I wanted to show the underbelly of Chinatown,” he said.

When he and Josh unearthed the tightly wound reels of film that had been in storage in their garage, Chuck wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with the celluloid trove. Josh, though, grasped its importance and pushed his father to make a documentary. He agreed, and it became a family project – and an expensive one. Digitizing the film cost about $1 a foot. “We paid out of pocket,” Chuck said.

Josh, a self-taught filmmaker, quit his job to focus on the documentary. “Working with Josh was a blessing as we got to know each other as adults,” Chuck said. Chuck’s wife helped support the work with her salary and became the project’s bookkeeper. The collaboration wasn’t always smooth: “There was a lot of apologizing,” he said.

“Chinatown Rising” debuted at the Castro Theater in May 2019 before an audience of about 1,200.” I can still recall how overwhelmed we felt as our production team made its way onto the stage for the Q and A. Filmfest sponsors said it was the first standing ovation they’ve ever witnessed at a CAAM film festival,” Chuck said.

Since then, the film has been shown about 150 times, and Josh thinks the number will rise to 200 by the end of the year. What’s next? Harry Chuck has no specific projects in mind, though an update to the International Hotel saga is a possibility, or maybe a documentary about busing and integration.

“Josh and I are extremely grateful for this experience,” he said. “We wish every parent and adult child could discover the joys of telling their life stories.”