Intent at eight years old on making art everyone can see, Mexican artist forges path to widespread public acclaim

When he was eight years old, Victor Mario-Zaballa told his family he was going to be a public artist when he grew up. “I wanted to make art that everyone can see and enjoy.” Today, his tile and cut-metal works adorn the entrance to the 16th St. Mission BART station, the gates for the Visitacion Valley Club House, and many more public spaces around the country.

A self-described “self-disciplined nerd,” Zaballa began studying art books when his classmates were still learning to read. Instead of devoting his free time to playing ball or rough-housing, he studied art books at the library or hung out with his two favorite adults. His grandmother made chocolates in her handmade molds. His great-aunt was a toymaker. “They were artists, always creating something,” he said.

They made an unusual threesome walking to town – two women in indigenous dress and the exceptionally tall, young boy. “My aunt would also be peering around for discarded cloth and metal to make toys,” Zaballa said. “That’s art, you use what you have.”

It marked them as something of an anachronism in the rapidly urbanizing Mexico of the 1960s.

The apt apprentice

Zaballa was born in the Mexican state of Morelos in 1954 and grew up in Cuernavaca, the “hippie haven” of Mexico. Zaballa’s father was Aztec, his mother was Mexican. The third of six children and the most independent, Zaballa taught himself to paint by studying art books. By the time he was 12, he decided it was time to learn from the best.

One of Mexico’s great muralists, David Alfero Siqueiros, had a studio in Cuernavaca. Zaballa “prepared a portfolio and rang his doorbell. “I said, I’m an artist, too, and want to learn. I admire the work you do, and I want to work with you.” Siqueiros allowed him to hang around. “That’s the way you do it, you get a job with someone who is paid to do the work you want to do, and you learn the trade,” Zaballa said.

Rather than art school after graduation, Zaballa decided to attend a polytechnic institute, hoping to acquire engineering and applied science skills. “When you do public art, you need to understand design and how metals function,” he said. But a year later he dropped out. “They were training bureaucrats who would sit behind desks and approve plans.” He wanted to create things. “There’s always something I want to do: images I want to see, sounds I want to hear, flavors I want to eat,” he said, uncovering a pot of mole sauce on his stove.

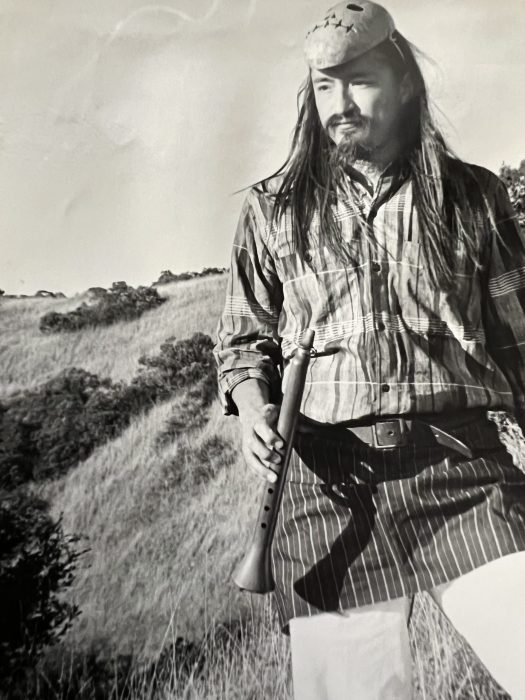

Because “an artist needs to be able to see,” Zaballa set out to learn photography. When he knew enough to benefit from an apprenticeship, he once again approached the best in the field. He was hired as a “gofer” for what he deemed the best commercial photography studio in Mexico City.

When he wasn’t carting coffee or sweeping the floor, Zaballa studied the professionals. When the time was right, he showed one of the partners his work, gaining both a mentor and a limited partnership in the firm. But photographing ads for magazines, while lucrative, became too routine. After two years he moved on.

The Toltec influence

An internship at the Siqueiros Foundation of the Arts in Mexico City allowed Zaballa to participate in the exciting counterculture of the city. “Nothing impacted me more and freed my heart and mind more than the Toltec philosophy,” Zaballa said, of being true to oneself rather than learned beliefs and expectations.

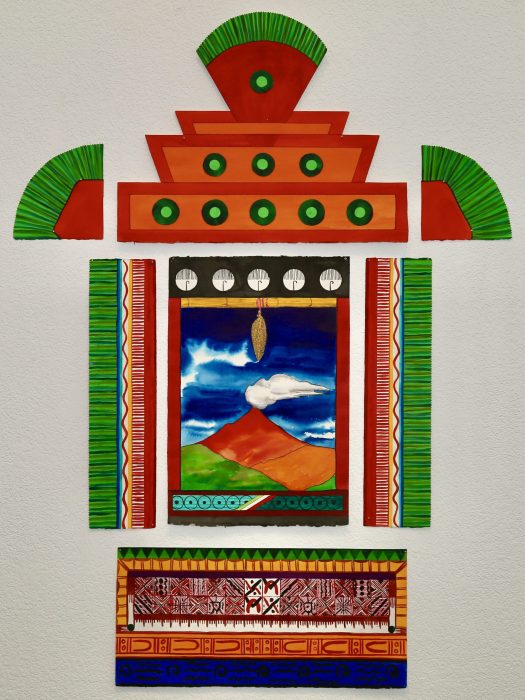

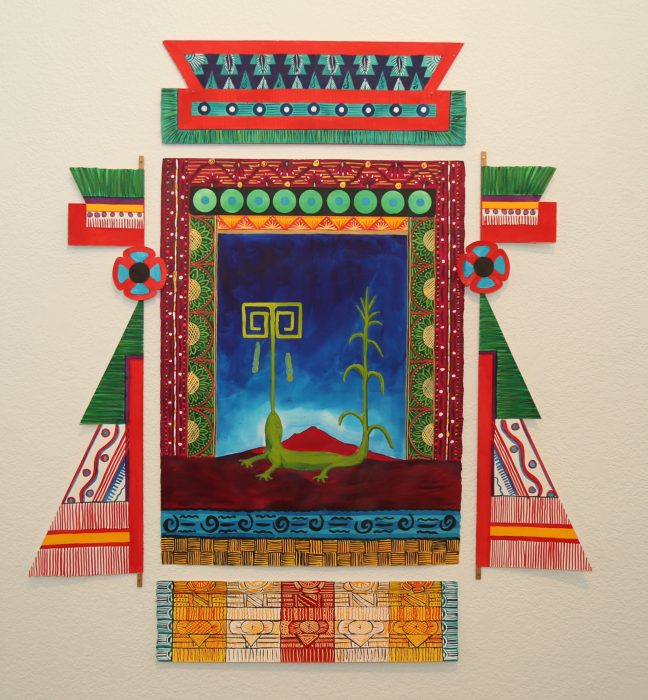

He had been focused on painting landscapes but began incorporating the Toltec belief that we exist simultaneously in multiple dimensions. He added information on the phases of the moon, the planets on the horizon, and the time of the day and season of the year – all represented as a picture inside a picture.

The painting on the left is El Popo, (the male volcano or warrior). At right is El Sueno, (the dream). (Photos courtesy of Victor Zaballa)

In 1980, when he was 26, Zaballa traveled to the United States to find a gallery where he could show his work. He liked the “vibes” of San Francisco, “so similar to those of Mexico City,” but the galleries he visited suggested he try the Mexican cultural center. But he wanted his works in an art gallery: “I’m an artist.”

Back in Los Angeles, the first gallery owner who saw his work bought his entire portfolio. For several years, he traveled across the border to bring his work to the U.S. But his work went on hiatus for five years when a U.S. Passport agent in San Francisco wrongly insisted that Mexican artists could not work in this country. While waiting to be issued another passport, Zaballa remained in the Bay Area, volunteering for film, music, and art projects while supporting himself as a handyman and window washer.

When his papers came through, he was finally able to apply for public art contracts.

His earliest commissions were for train stations in Arizona, Michigan, and Washington, and the 16th Street BART station. Other contracts included the wall and floor tiles at the San Jose Mexican Heritage Plaza, and the “sunrise” grills decorating the façade of Sacramento’s Capitol Garage.

His most recent contract is for a manhole cover next to a lake in San Francisco’s McLaren Park. He’s designing a kinetic stainless steel and plexiglass butterfly on a post that will move with the wind. “They wanted copper but that is too attractive to resell, so we’re doing it in stainless steel.”

Reviving pre-Columbian music

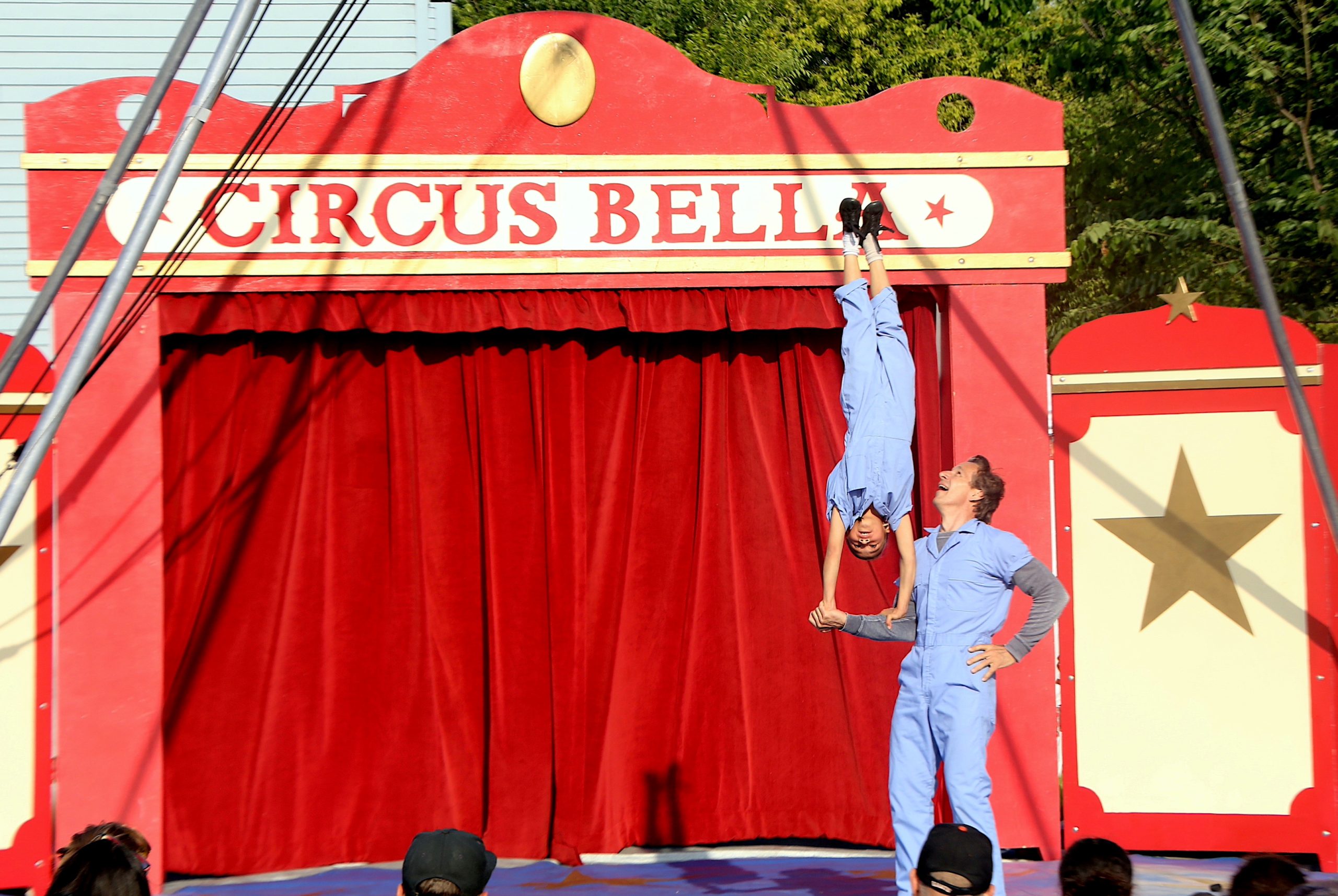

He continues painting and exhibiting in museums from Monterey to San Francisco. He’s called upon to build public altars and other pieces for El Dia de los Muertos, and other Mexican holidays. This year, he built a giant hummingbird altar for SOMArts and a giant kite for Davies Symphony Hall. Both were made of cut paper and paper mâché and glowed like stained glass under the changing light.

Yet Zaballa is never satisfied with the status quo. He’s always seeking something new to learn or create. In 1989, after studying pre-Columbian wind and percussion instruments in museum collections, he developed replicas, composed music, and recruited an ensemble to introduce these sounds to today’s audiences. Cancion de Obsidian, with Zaballa on the clay pot, flutes, and gongs, opened the 2023 San Francisco Symphony’s El Dia de los Muertos celebration and has previously performed at the Lincoln Center in New York, the DeYoung and Mexican museums in San Francisco.

He’s also taught art history at the University of California-Berkeley and the San Francisco Art Institute.

Zaballa married well-known Swiss writer Melina Moser a few years ago. They met through mutual friends. He is not close to remaining relatives in Mexico, but counts fellow artists among his family – as well as a few doctors along the way. He’s gone through some serious health scares: kidney failure followed by eight and a half years on dialysis waiting for a transplant; and a stroke that forced him to relearn to walk and talk. “My doctors are my friends; they’ve advocated for me and saved me,” he said.

They saved a life uniquely created by Zaballa himself. “I always knew what I wanted to do, all I needed was to be true to myself and start moving forward to achieve it.”

Pilar

Excellent art and excellent writing!