‘Wild writing’ softens clinical healthcare leader’s shift to solo career and enriches retirement

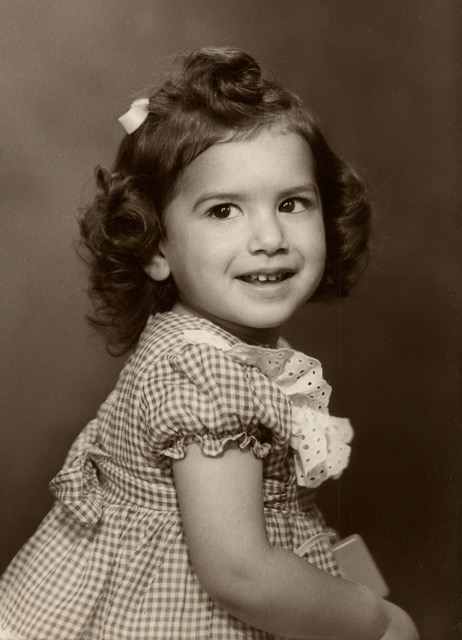

Kathryn Santana Goldman showed an affinity for science as early as grammar school when she captured and chronicled a variety of insects found in her backyard.

“My parents had one of those 30-volume encyclopedia sets that I used to look up the insects and document my findings in a small notebook,” she said.“I especially liked beetles, and I would pin them on a Styrofoam board and keep them on a designated shelf in my bedroom closet just below my dress shoes,” she said.

Her working years began in nursing, one of the few careers open to women besides teacher and secretary, she said. She started with the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War then on to work as director of nursing at a home health and hospice care company in the city. “It was a demanding job, and we were providing home care for patients at the height of the AIDS pandemic.” She later joined Kaiser Permanente as a national clinical team lead and Genentech as a leadership development consultant.

She wound up her career in 2022 after 12 years in her own executive coaching firm, KSG Consulting in San Francisco, which served scientists and doctors in the biotech and healthcare industries. One example of her work was using neuroscience techniques to help her clients cope with interpersonal tensions within the groups they led.

She taught them the ABC technique: becoming aware of their body’s responses to stress, such as headache, neck or chest tightness; consciously pausing by taking a deep breath, lowering the sympathetic nervous response; and being curious about what triggered the response. It’s a technique, called the Learning Mindset, often offered to heads of business to improve their leadership skills.

Poetry as panacea

As for the stress of going it on her own in business, Goldman also relied on poetry. Since 2020, she has been facilitating a monthly, five-person poetry group, “San Francisco Wild Writing Women.”

“Writing poetry helped me navigate the mercurial nature of running my own corporate consulting business,” she said. “Releasing my thoughts without constraint helped me process my feelings about not working with the safety net of a corporation.”

The group formed in 2017, after meeting at a poetry class at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. They just published a first collection of poems, “Season Lightly with Salt.” Members share input on one another’s poetry at once-a-month meetings rotated at one another’s homes.

That includes Goldman’s apartment in The Presidio Landmark, which she shares with Fred, her husband of 24 years, a retired tech entrepreneur. They also own a home in downtown Napa, where she holds poetry workshops at her synagogue, but keep a frequent foot in San Francisco. In addition to her poetry group, she teaches poetry writing once or twice a year at the Osher Institute.

Twice a week, Goldman visits her 97-year-old mother, who lives in an assisted living facility in Burlingame. Her brother, who is nine years younger, also lives in Burlingame and just became a grandfather. “My husband and I, having no children of our own, are thrilled to have a new grandnephew,” she said.

She also has eight cousins who live in the Bay Area with their families.

Bayview beginnings

Goldman grew up in the Bayview District in the 1950s and remembers her father hoisting her five-year-old self up onto a cowboy’s horse as he was driving longhorn cattle down Third Street towards the slaughterhouses. “I was terrified of the long horns, but the cowboys thought it was quite a lark,” she said.

Goldman’s mother’s family, the Martinucci’s, lived on one side of Third Street and her father’s family, the Santana’s, lived on the other. Her own family lived on Kirkwood Avenue until moving to suburban Belmont when Goldman was a junior in high school. “My mother drove me into the city daily so I could finish school with my friends,” Goldman said.

Goldman’s dad was a teamster for the Pacific Motor Trucking Company. Her mother was a keypunch operator for Schlage Lock in Visitation Valley, and then for Cal Trans in Foster City.

Despite being a poet, rock singer, and keyboard player in a high school band that leaned toward Jefferson Airplane and Janis Joplin, Goldman made the honor roll in her Catholic high school, acted in some high school plays, like “South Pacific,” and “didn’t get into trouble,” she said.

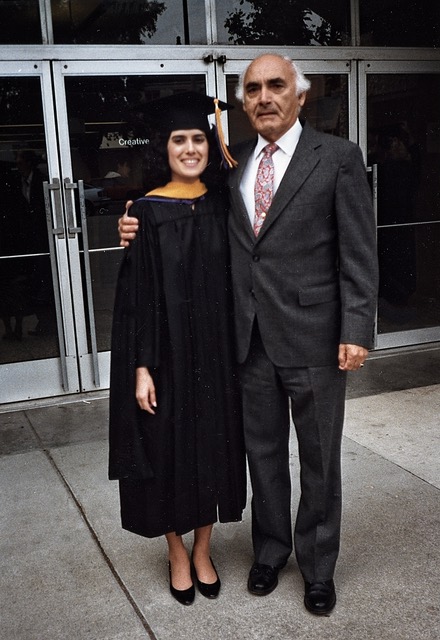

Goldman got her registered nurse license at St. Luke’s School of Nursing in San Francisco along with an Associate of Arts degree from City College of San Francisco. After graduating in 1973, she joined the Air Force, which stationed her in the U.S. working with wounded soldiers returning from the Vietnam War.

Goldman, 72, describes herself as “outgoing but not an extreme extrovert.” Being in the Air Force boosted her self-confidence. “After that, I felt I could go anywhere, take care of myself, and do well,” she said.

Mexican heritage

Her challenges didn’t just come from the rigors of military life. “With a deep tan and long curly brown hair, my Mexican heritage defined my looks at the time,” she said, “and I was refused service in restaurants, kicked out of bars, and called derogatory names.”

After three years in the Air Force, Goldman took advantage of the G.I. Bill to earn a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and a Public Health Nurse Certificate at San Jose State University. While studying, she worked in intensive care at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View.

By this time, becoming interested in being able to influence healthcare systems, she enrolled in San Francisco State University’s master’s program in health education. After getting her degree in 1985, she began working at Health Resource Management in San Francisco, a private nonprofit healthcare company where she said she “loved wearing three hats.” There, she managed staff, oversaw home care at the height of the AIDS pandemic, and worked with business partners in public health policy and care delivery.

In 1991, she joined Lifesource, a private homecare infusion company in Larkspur, to manage their home infusion therapies program. The next year, she was recruited by Kaiser Permanente to help develop their home infusion teams in Santa Rosa, San Rafael, and South City. From this job, she moved into other positions within Kaiser, eventually working around the country on disease management interventions to improve patient conditions.

Value of community

In 2000, she was recruited by the biotech company Genentech, where with a staff of 70, she helped patients secure insurance coverage for medications, and followed that with project management work, organizational improvement activities, and working with leadership teams. After Genentech merged with the Roche Group in 2009, going from a small to a global company, Goldman left to become a consultant, including to Genentech.

Those years instilled in her the value of networking, she said, which helped her establish community while being out on her own in her consulting business. She considers her involvement with San Francisco’s SMART a program, which mentors bright but opportunity-challenged fourth-graders all the way through high school, “one of the most important things I’ve done in my life.” She personally mentored a girl for six years who eventually won a full scholarship to Pomona College.”

Poetry has been a backstop throughout her life, from high school through her working years and into retirement. She had been taking poetry classes at the Osher Institute for a few years when, in 2020, she discovered a five-month, online class for writers who want to facilitate the process for others.

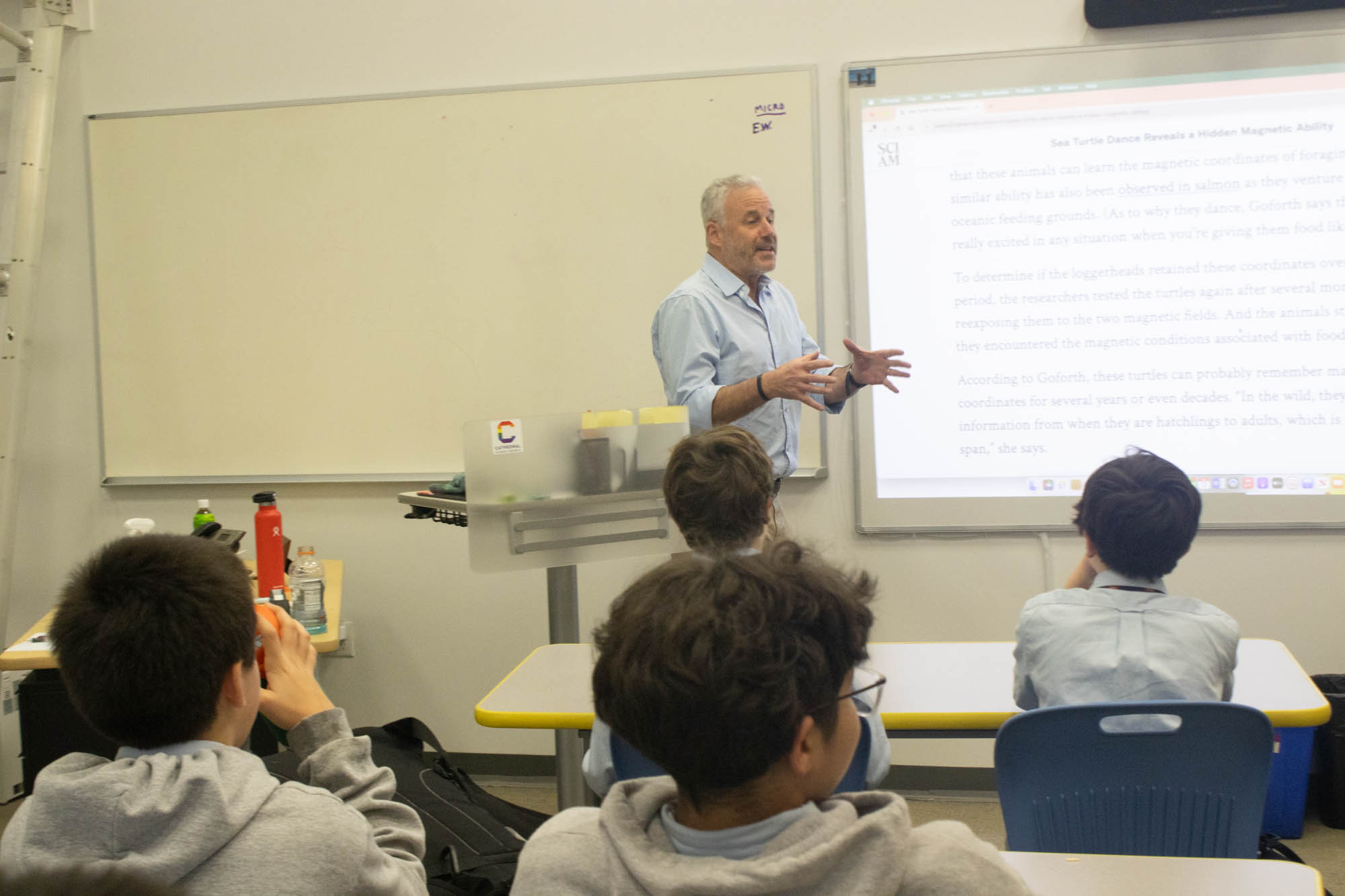

The teaching model, for which she earned a certificate, fit her idea of “a wild writing process with health care benefits of expressive writing.” She started a private class on Zoom, much of it based on the work of Dr. John Pennybaker, who espouses the psychological and physiological benefits of journal writing through trauma or hardship.

Unfiltered expression

It was the beginning of pandemic isolation. “I identified a need to help folks generate resilience during a time of uncertainty,” she said. “The class provided participants a tool to ground themselves through unfiltered expression.”

Goldman begins each 90-minute session with a grounding meditation, she said, then “we set an intention of whatever is bubbling up that we need to address.” She reads a few lines of poetry from a list of her favorites – Leonard Cohen, Jack Kerouac, Ellen Bass, James Crews, and Mary Oliver among others – as a prompt for members to write “wild, sloppily, loose and imperfectly” for 10 minutes.

“I do three rounds and then we stop. We close with a short meditation during which I invite them to reflect on what they have written and what action they may want to take on what they discovered,” she said.

Goldman started writing poetry in high school, where her English teacher had them create their own works in classical styles. ”I must admit, iambic pentameter was never my favorite style,” she said, but she did enjoy reading her work at assemblies.

As for herself, she writes free-verse, poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme. “I’ve had some success with some of the poetry formulas like sonnets,” she said, “but I prefer a format where my thoughts are not constrained by a structure. “

Not My Father’s Pasta by Kathryn Santana Goldman

“In Sicily, we were poor but resourceful!” – Chef Paolo, Taormina, 2023

Chef Paolo was a younger version

of my father with a shiny bald head,

strong arms and intimidating grimace.

He was teaching us how to make pasta.

Gesturing with one hand he plunged the other

into a bag of semolina, tossing a handful on the table.

He caressed the flour, teased it into a swirl,

then gently rained water onto the dry powder.

Like a matchmaker, his broad fingers

coaxed the two strangers into a marriage.

Kneading the resistant grains and warm liquid until

they yielded to his touch.

With a roll and twist,

Fusilli, Bucatini, Orecchiette

spilled from his hands

small, delicious sculptures.

Like his pasta,

we are transformed.

Ready to follow his lead,

we grabbed flour and water.

I dig my fingers into

my raw materials and I am

in my childhood home,

my father beside me.

He chuckles as he wipes flour

off my nose. The ghost-scent

of his Old Spice mingles with

the aroma of fresh basil.

Dad watches me

as I pull and tug on my dough,

a glass of red wine in his hand,

offering “It needs and egg.”

Then he is gone.”