He rode the rails, he slept on the streets, Kevin Fagan spent decades reporting on the homeless for the San Francisco Chronicle

It’s a Friday night at Chief Sullivan’s, an Irish-themed bar in North Beach, and The Irish Newsboys are about to perform one of their signature Irish tunes. But don’t expect to hear a song about leprechauns and pots of gold. The Newsboys’ repertoire favors songs about Irish freedom like “The Rising of the Moon” and celebrates rascals like the road agent in “Whiskey in the Jar.”

Those musical choices reflect the taste and experiences of Kevin Fagan, the group’s lead guitarist, who has written extensively about the unhoused and the down-and-out during three decades as a reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle.

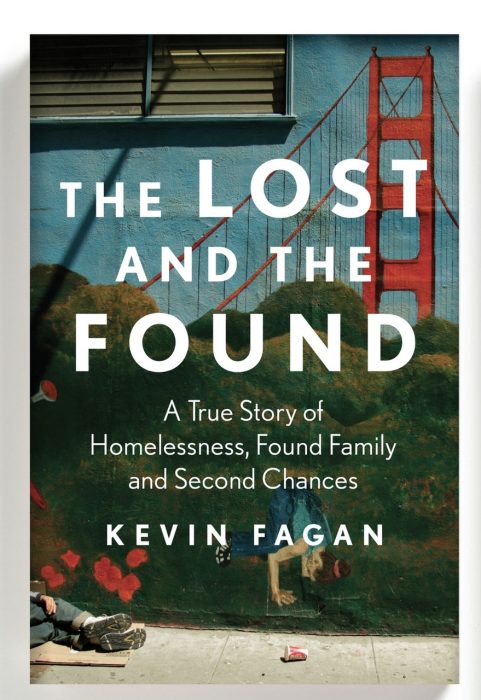

Recently retired, Fagan, 67, is the author of “The Lost and the Found,” a deep dive into the lives of two of the homeless people he met while covering San Francisco’s pervasive and seemingly intractable housing crisis. No longer bound by the strictures of objective newspaper journalism, Fagan, who experienced homelessness as a youth, writes with passion and sympathy. “Homeless people aren’t just one-dimensional caricatures. There’s much more than that; everyone was somebody’s baby with a lot of hope.”

For years, he was one of the few reporters in the U.S. with a beat focused on the homeless. He and Chronicle photographer Brant Ward spent months on the city’s streets, even camping many nights on “Homeless Island,” a traffic island on the edge of San Francisco’s Mission District.

Their time on the street was the basis for a prize-winning 2003 series, “The Shame of the City,” that received widespread attention and raised embarrassing questions about how San Francisco was able to spend hundreds of millions of dollars helping the homeless with such disappointing results.

His stories about two of the homeless people he met while reporting the series and subsequent follow-ups – Rita Grant and Tyson Feilzer form the core of “The Lost and the Found.”

His hopes for the book were modest. “I just wanted it to sell enough copies that I wouldn’t be embarrassed.”

Released in February, the book has been well received, garnering positive reviews in major publications, including the New York Times, The Guardian, and The New Yorker. Fagan has been a guest on NPR, interviewed by numerous publications, and was honored by outgoing Mayor London Breed, who proclaimed “Kevin Fagan Day” shortly before he retired.

The shame of the city

The “Shame of the City” series was compassionate but unsparing in its depiction of human misery and despair. In part one of the five-part series, Fagan wrote:

The day everyone learned Tommy’s rotting flesh killed him was pretty much like any other day on the traffic island.

Vina, the one-legged woman with broken teeth, weaved her wheelchair in and out of traffic all morning, panhandling with a cardboard sign that read, “Anything helps.”

Michelle, the willowy transvestite, dozed alongside her heaped shopping cart, occasionally waking to stare at the cars.

Little Bit Susan, the tiny prostitute, wasn’t at her usual spot on the sidewalk — but that was only because she was in the hospital again from another feverish flareup of one of the abscesses on her neck.

” I wouldn’t say I became numb, but I did become toughened,” said Fagan, when asked how witnessing such scenes affected him. “As a result of my upbringing as well as my work, nothing, and I mean nothing, surprises me anymore.”

He describes his youth and motivation for writing about the homeless in the first chapter of “The Lost and the Found,” writing: “As the saying goes. ‘Write what you know.’ I know what it’s like to be poor and not have a home.”

He grew up in various parts of the East Bay and Nevada, the child of blue-collar parents “who never really understood how to relate to kids.” His father grew up on farms in rural Oregon and Washington. His mother was raised “in hardscrabble mining-camp tents and shacks in Nevada.” They divorced when Fagan was 13.

His dad left the country after the divorce, and Fagan was left with a mother who was more interested in going back to school than being a single mom with a difficult teenager. The relationship didn’t work, and when he was 16, his mother told him to get out. (They later reconciled.)

Fagan had a part-time job cleaning houses and moved to a garage in Union City. After a stint in junior college, he enrolled at San Jose State University, where tuition and dorm fees were low. But when school wasn’t in session, students had to leave the dorms, so Fagan sold his motorcycle and generally slept in the cramped back seat of his Volkswagen bug on the outskirts of the campus.

“It was cold and wet and scary for a kid,” he said. “I washed up in gas station bathrooms and cursed the world.”

On the road with a guitar

By the time he was 20, Fagan had a degree in journalism and spent the next few years traveling and busking (playing music on the street) in Europe, England, New Zealand, and Australia. Busking doesn’t bring in much money, but he was young. Sleeping by the road or in a “dive” hotel didn’t bother him. He lived in a closet for a while.

Like many young people, he’d occasionally smoke marijuana or indulge in mushrooms. But he managed to avoid alcoholism and hard drugs and ultimately became a successful journalist, husband, and father.

Even so, he wrote, “I’ve always said that growing up the way I did made me strong. But as therapists like to point out, leaving home the way I did, and being homeless even in the truncated way I was a kid left trauma.”

Newspaper jobs were hard to get in the ‘80s and ‘90s when he returned to San Francisco, but Fagan landed at two of the Bay Area’s largest: the Oakland Tribune and then the San Francisco Chronicle. Known as a fast, fluid writer with lots of energy, he was often the lead reporter – and sometimes editor – on breaking news stories, disasters, and major crimes.

He didn’t mind getting his hands dirty or his feet wet. Over the years, he witnessed seven executions at San Quentin, rode the rails on his way to a hobo convention, and wrote extensively about serial killers, including the Unabomber, the Zodiac, and the Doodler, and covered innumerable murders and wildfires. When the Russian River flooded, he navigated the river in a motorboat, interviewing along the way while keeping his notes dry in a plastic bag.

Covering the homeless, though, was always closest to his heart.

“I always felt like I was doing a public service by communicating the extent of homeless misery and highlighting things that need fixing as well as probable solutions, and that made me feel good,” he said.

8,300 still living on the streets

But the persistence of homelessness in San Francisco frustrates him. Despite spending at least $2 billion over the last decade, homelessness in the city has stayed relatively steady: from about 8,600 in 2004 to about 8,300 last year, according to the city’s annual “Point in Time” survey.

Covering the homeless was not a suit-and-tie job. After a night spent on Homeless Island, he would sometimes find that his legs itched from the pigeon mites that infested his blanket. At times, he even had to burn his clothes. And like many hard-driving journalists, he found that the job kept him away from his family. ‘” I missed a lot of my daughter’s childhood,” he said with obvious regret.

However, spending time on Homeless Island afforded him a real-time view of the homeless, and the island was where he met Rita Grant.

Grant was an archetypical Florida surfer girl, skilled in gymnastics, married to a professional diver, living on a boat with her five kids. But drugs and alcohol derailed her life. She divorced and moved to San Francisco, ultimately washing up on Homeless Island, addicted, sick with abscesses, and panhandling.

It took time to build trust, but Fagan got to know her. They became friends, staying in touch for a decade. The story of her life on the streets and eventual recovery is detailed in “The Lost and Found.” She died of cancer, surrounded by her family, in 2023.

Fagan continued to cover the homeless, and years after his Homeless Island reporting, he met Tyson Feilzer, sprawled on a scrap of cardboard on the Embarcadero.

Feilzer was from Danville, an affluent Contra Costa County community, the son of a real estate agent and an accountant. He had a solid education and worked as a salesman and a mortgage broker. But he lost his job during the 2008 recession and became addicted to alcohol and then heroin.

Fagan wrote about him in the Chronicle. The story went online, and Feilzer’s brother, Baron, who was living in Ohio, saw it. Baron raised money for his brother’s rehabilitation and flew to San Francisco to find him. With Fagan’s help, he did.

Reunited with his family, Feilzer went into rehab programs in the Midwest and appeared to be headed for a decent life. But he couldn’t stay clean. He moved back to San Francisco, returned to the streets, and to heroin. Before long, he was dead of an overdose.

“It was just heartbreaking,” said Fagan.

Gavin Newsom, then San Francisco’s mayor, read about Grant’s reunion with her family and launched a program called Homeward Bound that works to unite homeless people with their families. The program reportedly has had success, and in March, Mayor Daniel Lurie said he plans to bolster it. “Homeward Bound,” said Fagan, is my proudest achievement.”

Although being the subject of news coverage rather than the author of it is new to him, Fagan isn’t particularly shy. “I’ve been a performer, so I’m used to putting myself out there.” While he sometimes misses the adrenaline rush of a big story, he’s happy not to be chasing daily scoops. “I got to the point where I had written most of the (daily newspaper) stories I wanted to write,” he said.

His high-profile coverage of serial killers and other criminals made him a target at times. “I’ve been shot at, slashed, attacked, endured death threats. I don’t miss that.” Nor does he miss the discomfort of sleeping on sheets of cardboard. “I’m a bit old for that,” he admits.

Promoting his book is time consuming, but not in the burnout-producing mode of a daily newspaper job. There’s more time for music. There are Irish antecedents in his family tree; “I grew up with the Clancy Brothers on Dad’s turntable.” The monthly appearances by the Newsboys at Chief Sullivan’s generally draw a decent crowd, and he performs frequently in other venues. When colleagues at the Chronicle retired, Fagan was known for his humorous and sometimes a bit ribald farewell ballads.

He lives in Walnut Creek with his wife, journalist Carolyn Newbergh; they have a grown daughter.

Essays and a novel on the horizon

Like the stereotypical reporter of hardboiled fiction, he’s had an unfinished novel in his desk for years. He’s working on it and writing a series of essays for his publisher, Simon & Schuster.

As he moved into a new phase of his career, he embraced new forms of storytelling. In 2001, he wrote and narrated an eight-part podcast about the Doodler, a serial killer who preyed on gay men and has never been caught. “The Lost and the Found” allowed him the room to delve much deeper than he could as a newspaper writer.

Fagan is disturbed by the decline of local news and the failure of some media organizations to stand up to attacks by the Trump administration. But he’s optimistic about the future of the news business. “The passion and drive of younger journalists still streaming into the business is especially inspiring,” he said.

“They’re still filled with the same fire we had to make the world a better place, shine a light on need, hold the powerful accountable, comfort the afflicted — all those motivations we’ve intoned and cherished for as long as I’ve been a journalist.”

David Jensen

Great story!!!…and Great Book!!!…for the record, it’s actually Danville and not Dublin…